|

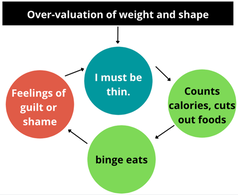

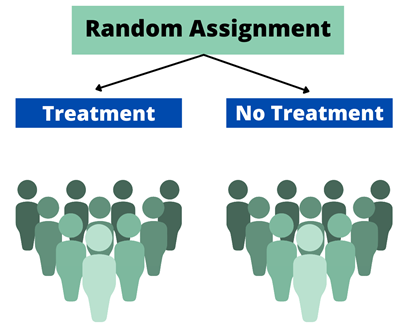

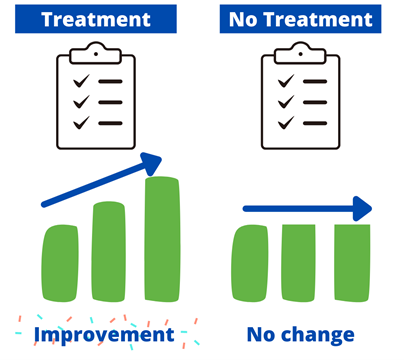

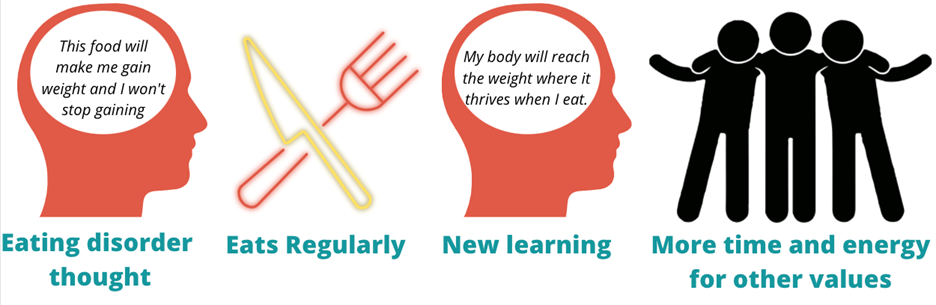

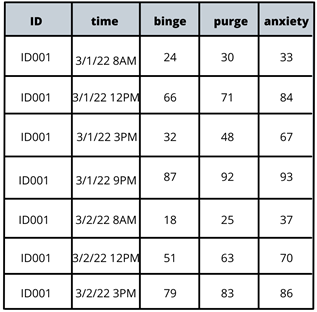

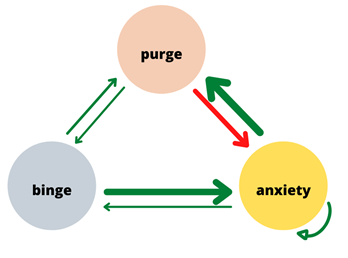

Written by Claire Cusack, M.A., First Year Graduate Student You may be wondering how eating disorder treatments have been developed, how that is currently shifting, and what this might mean for you in your recovery. This post centers these questions. I briefly describe what has been done in the past research, some ways our lab is changing the game, and what that means for you. How we develop treatments The process for developing evidence-based treatments for psychiatric disorders is undeniably complex. At its most basic (and perhaps ideal) form, the process involves developing a theory (e.g., a testable hypothesis of what causes or maintains disorders given a certain set of assumptions) of what causes internal suffering and/or challenges in work, school, or social life, coupled with strategies to address this cause. Generally, a group of people with said suffering complete surveys inquiring on a range of symptoms. Then, a random half of participants receive the treatment, and the other half does not (i.e., a randomized clinical trial; RCT). The group of participants who do not receive the treatment are referred to as the control group, and they may be on a “waitlist,” or receive an existing treatment. After completing treatment, participants in both groups report their current level of symptoms again. If the group that received the treatment demonstrated improved therapeutic outcomes (e.g., less symptoms, less impairment, greater quality of life) relative to the control group, the treatment has initial empirical support.  If research accumulates with similar findings, this treatment may enter guidelines for treating a given problem. You may be familiar with this design in terms of new pharmaceutical drugs: there’s a pill with the actual medication and there’s a placebo or “sugar pill.” A similar process had been adopted to therapeutic treatments. To illustrate, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced1 is considered the gold standard treatment for eating disorders2–4. The idea behind this treatment is that over-valuation of weight and shape (e.g., thoughts like “I must be thinner,” “I will be rejected if I gain weight”) cause eating disorder behaviors (e.g., restrictive eating, binge-eating, purging, driven exercise). These behaviors fuel the eating disorder thoughts, and thus create a cycle. Therefore, when an individual starts Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced and engages in processes such as regular eating, evaluating thoughts, and weekly weighing, they learn to invest in other values (such as friendships) and manage uncomfortable emotions in healthier ways. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced is the leading evidence-based treatment for eating disorders. As several studies have replicated these findings, guidelines suggest that this approach is the frontline treatment for eating disorders2–4. Researching Groups and Treating Individuals Unlike many medical diseases, in psychology, we often don’t know what causes a disorder, and perhaps there are different causes that drive a disorder across individuals. The response rate across evidence-based treatments for a range of concerns is up to 50%5–7. This finding means that our best treatments work for half of people. There are many reasons why treatments are generally effective for half of people . One reason that may explain these rates are RCTs have historically compared groups, not individuals. For example, researchers average symptom scores for the group who received treatment and test whether it differs from the average symptom scores for the group who did not receive treatment. For example, do eating disorder symptoms decrease more in a group who received cognitive behavioral therapy versus the group who received dialectical behavioral therapy. There is value in studying groups. A group-level approach is important because it can be helpful for psychologists to know what “generally works.” The shortcoming is that RCTs risk assuming people with a disorder are the same (e.g., experience the same symptoms; respond to treatment in the same way), which often results in a one-size-fits all treatment8. Yet, therapy is often delivered to an individual. The decision to treat the individual is intuitive. However, despite decades-old calls to study individuals, research has largely remained at investigating groups[1]. On one hand this reality is discouraging because we still don’t know how to best treat individuals. On the other hand, work investigating individuals is growing. Though this topic is relevant to most mental disorders, the rest of this post will describe why and how our lab is centering the individual in studying eating disorders and developing personalized treatments for eating disorders. [1] Note: There has been some work investigating treatment at the individual level over the years, but this work lags in comparison. Further, the methods have not been that rigorous until recently due to smart phones and watches. Why study eating disorders within an individual? Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are eating disorders that enter the mainstream, but there are more than two eating disorders, such as, binge eating disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED). Most of these disorders share common features, such as weight and shape disturbance, restricting food intake, binge eating, and compensatory behaviors. Despite these similarities, eating disorders look very different across diagnoses (e.g., bulimia nervosa vs ARFID) and within one disorder (e.g., one person with anorexia nervosa may binge and purge and another person with anorexia nervosa may not)9–11. OSFED is the most common eating disorder diagnosis12 and it captures eating disorder presentations that do not “neatly” fall into other eating disorders. This diagnosis includes people who may meet criteria for anorexia nervosa aside from being underweight, people who would meet criteria for bulimia nervosa but purge one day less a week, people who would meet criteria for ARFID but do not have a nutritional deficiency, etc. Further, co-occurring concerns, such as anxiety, depression, substance use, etc., may also influence how a person struggles with eating, weight, and shape concerns. What this suggests to us is eating disorders can look very different from person to person! This reality causes challenges for scientists and clinicians who are left asking questions like, “Where do we start treatment?” “What treatment will be most effective at relieving symptoms and most efficient in terms of time and money?” The answers to these questions may depend on the person, which is why our lab is studying personalized approaches to eating disorders. How do we study eating disorders within one person? To find an effect of treatment, we need observations, usually lots of observations. Many observations help researchers not only gather enough observation for analyses, but it also provides us with rich detail about how eating disorders look so that we can develop and implement the best treatments. When studying groups, we gather observations by recruiting a large number of participants. When studying individuals, we gather observations by asking individual participants to report on symptoms many times a day for several days. These symptoms are obtained from surveys delivered to individuals’ mobile devices. We then have lots of information on one person, so then for each person, we have something that looks like this: From the example above, what we have is a sheet for one person (ID001) reporting on their urges to binge eat, urges to purge, and current anxiety. What we see is that for this person, their urges to engage in eating disorder symptoms, as well as the anxiety they are experiencing within a given moment, change over the course of the day (e.g., anxiety ranges from 33 at 8AM to 93 at 9 PM on March 1). What we can then do is apply statistics to model how these different symptoms relate to each other across time. In this figure, the green arrows represent positive relationships, and the red arrow represents a negative relationship. For instance, increased urge to binge eat is related to increased urge to purge. However, an increased urge to purge is related to less anxiety. By modeling a person’s specific symptom relationships, we can use data to help clarify our existing case conceptualizations and determine which intervention maps onto symptoms that may be driving an individual’s distress11. For this person, we may wonder if purging serves the purpose to reduce anxiety, which may be caused from binge eating and/or weight and shape-related concerns.

Regardless, you can imagine how these relationships vary across people. By studying the individual, we are moving toward personalized treatment, or “precision medicine,” so that your treatment makes sense for you, rather than what *might* work for the group. As it stands, our gold-standard treatments work for 50% of individuals with eating disorders. I think researchers and clinicians can do better by you, participants and/or patients. Our lab find promise in using individual approaches to data analysis to inform personalized treatment to do just that. Our preliminary data using a data-driven approach to personalized treatment shows reductions of eating disorder symptoms after treatment, as well as one-year post-treatment for the individual13. What this means is that the improvements in eating disorder symptoms may be maintained over long stretches time. When the current state of the field shows that half of individuals achieve full recovery, with many experiencing diagnostic cross-over (e.g., meeting criteria for anorexia nervosa and later meeting criteria for bulimia nervosa), we hope that these insights offer a glimmer of hope that the eating disorder field is progressing while keeping you at the center of our work. How you can play a role in advancing eating disorder treatments We are launching a new treatment study for eating disorders that tests a Personalized Treatment approach versus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced. Participants enrolled in this study will receive 20 sessions of free individual therapy for their eating disorder. To learn more about this study and see if you are eligible, please click this link which will direct you to our website. References 1. Fairburn, C. G. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. (Guilford Press, 2008). 2. Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z. & Shafran, R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a ‘transdiagnostic’ theory and treatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 41, 509–528 (2003). 3. Fairburn, C. G. et al. A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 70, 64–71 (2015). 4. Murphy, R., Straebler, S., Cooper, Z. & Fairburn, C. G. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 33, 611–627 (2010). 5. Carter, J. C., Blackmore, E., Sutandar-Pinnock, K. & Woodside, D. B. Relapse in anorexia nervosa: a survival analysis. Psychol. Med. 34, 671–679 (2004). 6. Trivedi, R. 1975-, United States. Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Services Research and Development Service, Durham VA Medical Center, & Duke University Evidence-based Practice Center. Evidence synthesis for determining the efficacy of psychotherapy for treatment resistant depression. (Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, 2009). 7. Batelaan, N. M. et al. Risk of relapse after antidepressant discontinuation in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of relapse prevention trials. The BMJ 358, j3927 (2017). 8. Spring, B. Evidence-based practice in clinical psychology: What it is, why it matters; what you need to know. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 611–631 (2007). 9. Forbush, K. T. et al. Understanding eating disorders within internalizing psychopathology: A novel transdiagnostic, hierarchical-dimensional model. Compr. Psychiatry 79, 40–52 (2017). 10. Levinson, C. A. et al. Personalized networks of eating disorder symptoms predicting eating disorder outcomes and remission. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 2086–2094 (2020). 11. Levinson, C. A. et al. Using individual networks to identify treatment targets for eating disorder treatment: a proof-of-concept study and initial data. J. Eat. Disord. 9, 147 (2021). 12. Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G. & Tavolacci, M. P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 1402–1413 (2019). 13. Levinson, C. A. et al. Longitudinal group and individual networks of eating disorder symptoms in individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci.

0 Comments

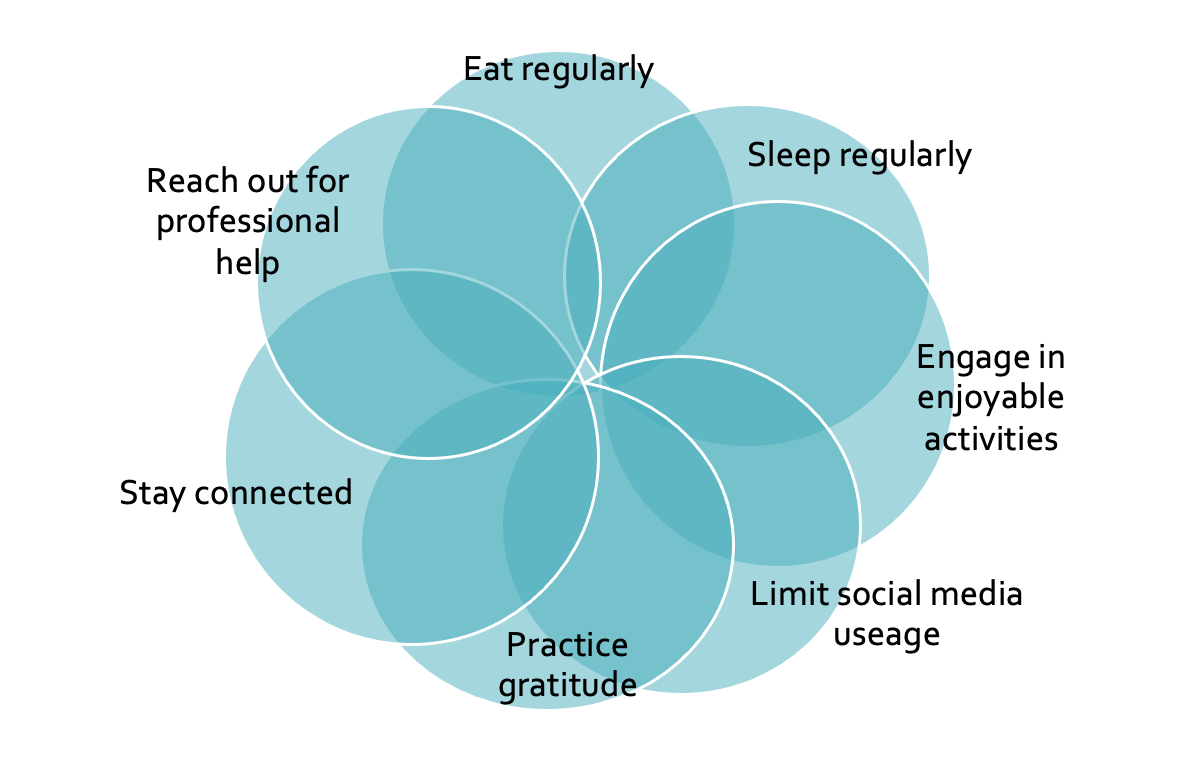

Written by Jamie-Lee Pennesi, PhD, Postdoctoral Research Associate This blog was first posted on the F.E.A.S.T. website on 15th Dec 2021: https://www.feast-ed.org/eating-disorder-relapse-how-to-prevent-it/. The following blog is directed toward for someone who has or has previously had an eating disorder in mind, but it can also be helpful for a friend or a loved one, a therapist, or others who wish to support someone with an eating disorder or someone who is recovering from an eating disorder. In this blog I will talk about eating disorder relapse and provide helpful strategies and tips on how to prevent relapse. Recovering from an eating disorder is not easy. It takes a lot of courage, strength, perseverance, hard work, and support. Most people do not recover from an eating disorder without a few slips or occasional setbacks; that is normal, expected, and okay. ‘Relapse’ is when someone who is in recovery goes back to disordered eating or weight control behaviors. This is different from a ‘lapse’ which is a temporary slip or return to a previous problematic behavior (usually a onetime occurrence). It’s not uncommon for people who have recovered from an eating disorder to relapse. In fact, up to 60% of people who recover from an eating disorder will relapse in the first 1-2 months after treatment. The best way to prevent a relapse is through ‘relapse prevention’. Relapse prevention is a cognitive-behavioral approach used in treatment to identify and prevent high-risk situations, such as re-emergence of problematic eating and weight control behaviors, or negative thoughts about eating, body, weight, or shape. Relapse prevention often involves a personalized ‘relapse prevention plan’. A relapse prevention plan is developed during treatment with the therapist and is tailored to you. Here, one size does not fit all. For the best chance of success, a relapse prevention plan should include early warning signs, triggers, and high-risk situations specific to you, so that you can be prepared and ready to deal with any setbacks. A relapse prevention plan should consider the following issues:

Other strategies for preventing a relapse:

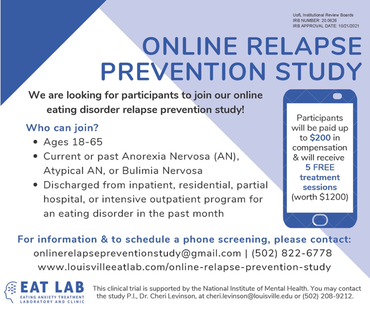

I hope this blog has provided you with important information about eating disorder relapse and given you useful strategies and techniques to consider using to prevent relapse. If you are looking for additional support or know someone who might need it, you may be interested to learn about our Online Eating Disorder Relapse Prevention Study. Participants are paid up to $200 in compensation and receive five sessions of free treatment which may help to decrease anxiety and eating disorder symptoms and may help to prevent eating disorder relapse. The information collected from this study may also be helpful to inform future treatments for eating disorders, prevent relapse, and promote full eating disorder recovery. We are looking for participants who 1) are aged 18-65, 2) have current or past anorexia nervosa, atypical anorexia nervosa, or bulimia nervosa, and 3) have been discharged from inpatient, residential, partial hospital, or intensive outpatient program for an eating disorder in the past month. Following a phone screening and online questionnaires, you will be asked to complete one of two five-session online treatment sessions and complete five follow up assessments. This study is conducted by the Eating Treatment Anxiety Lab at the University of Louisville and supported by the National Institute of Mental Health. For more information or to schedule a phone screening, please contact us at onlinerelapsepreventionstudy@gmail.com or (502) 822-6778. Further information can also be found on our website at www.louisvilleeatlab.com/online-relapse-prevention-study. References: BC Children’s Hospital, Kelty Mental Health Resource Centre (n.d.). Relapse prevention. Retrieved from December 8, 2021, from https://keltyeatingdisorders.ca/recovery/relapse-prevention/ Fursland, A., Byrne, S., & Nathan, P. (2007). Overcoming disordered eating. Perth, Western Australia: Centre for Clinical Interventions. Iulia. [@iuliastration]. (2021, October 13). Progress is not linear Or the artwork which allowed me to expand my creative universe. I was so nervous about posting this half a year ago because it was so different from my previous work. One day I just went for it and it became one of my most loved creations. Yet another reminder to let that inner voice lead the way. Prints via link in Bio (this design is also available on a mug) #iuliastration #illustrationart #digitalart #procreate #illustratorsoninstagram #womenofillustration #mentalhealth #strongwomen #empowerment #motivation #dailymotivation #progress #growth #growthmindset #affirmations #quoteoftheday #quotestagram #strength #positivevibes #innerchild #positivethinking #healing [Instagram photo]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/iuliastration Iulia. [@iuliastration]. (2021, September 9). Some days strength is just keeping it together – art and words by @iuliastration Prints via link in Bio #iuliastration #illustrationart #digitalart #digitalillustration #procreate #illustratorsoninstagram #procreateart #selflove #selfcare #yogapractice #spiritualart #yoga #meditation #growth #growthmindset #affirmations #feministart #motivation #dailymotivation #trusttheprocess #quotestagram #trustyourself #positivevibes #positivethinking #feminineenergy #goddess #strength #womenofillustration #illustrationoftheday [Instagram photo]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/iuliastration Iulia. [@iuliastration]. (2021, July 10). Cheers to you! Prints available via link in Bio Free worldwide tracked shipping on all orders of 3 prints or more with code ARTLOVE #iuliastration #illustrationart #digitalart #digitalillustration #procreate #illustratorsoninstagram #procreateart #selflove #selfcare #selfcareideas #spiritualart #lookwithin #meditation #growth #growthmindset #affirmations #motivation #dailymotivation #trusttheprocess #quotestagram #trustyourself #positivevibes #positivethinking #feminineenergy #goddess #strength #womenofillustration #illustrationoftheday [Instagram photo]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/iuliastration Iulia. [@iuliastration]. (2021, April 16). The journey of a lifetime Prints available via link in Bio #iuliastration #illustrationart #digitalart #digitalillustration #procreate #illustratorsoninstagram #procreateart #selflove #selfcare #selfcareideas #spiritualart #lookwithin #meditation #growth #growthmindset #affirmations #motivation #dailymotivation #trusttheprocess #quotestagram #trustyourself #positivevibes #positivethinking #feminineenergy #goddess #strength #womenofillustration #illustrationoftheday [Instagram photo]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/iuliastration Iulia. [@iuliastration]. (2021, February 3). With time and care we bloom with time and care we bloom Prints available via link in Bio #iuliastration #illustrationart #digitalart #digitalillustration #procreate #illustratorsoninstagram #procreateart #selflove #selfcare #selfcareideas #spiritualart #lookwithin #meditation #growth #growthmindset #affirmations #feministart #motivation #dailymotivation #trusttheprocess #bodypositivity #trustyourself #positivevibes #positivethinking #feminineenergy #goddess #strength #womenofillustration #ladieswhodesign #illustrationoftheday [Instagram photo]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/iuliastration Walsh, B. T., Xu, T., Wang, Y., Attia, E., and Kaplan, A. S. (2021). Time course of relapse following acute treatment for anorexia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(9), 848-853. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010026 Written by Julia Nicholas, B.S., First Year EAT Lab Graduate Student For many people, the holiday season brings gatherings with loved ones, cherished traditions, and a break from our everyday routines. If you are in recovery from an eating disorder, you may find that you have an uninvited plus-one tagging along to holiday gatherings: your eating disorder. Let’s talk about some strategies for talking back to eating disorder thoughts that may come up during the holidays. Navigating Holiday Meals It’s no surprise that many holiday traditions revolve around food. Food provides nourishment, connects us with our cultural heritage, and gives us a practical reason to gather: to cook and eat together. All this focus on food can be stressful for someone with an eating disorder. Holiday meals may disrupt your eating routine and you may worry that special holiday foods are “unhealthy” or that eating them will cause you to gain weight. It may be tempting to eat less in anticipation of holiday meals. It’s important to remember that regular eating is a crucial part of eating disorder recovery. For example, it helps prevent the cycle of restriction and binge eating (Fairburn et al., 2003). Following your regular eating schedule, including all your meals and snacks, can actually help you enjoy special holiday foods in moderation, because you will be less likely to feel extremely hungry and out of control while eating them. Continuing to eat regularly can help you live in line with your values, for example, by giving you the energy to spend quality time with your family and create treasured memories. Reconnecting with Loved Ones  Reconnecting with family and friends you haven’t seen in a long time may bring up concerns about your physical appearance. It doesn’t help that the first thing many people say when seeing someone after a long time apart is something along the lines of, “You look great!” In these situations, it may feel like there is a magnifying glass on your weight. Pause for a moment and think of someone you care about. Now, imagine you’re going to spend time with them for the first time in months. What do you look forward to? Their sense of humor, their knack for storytelling, their warm hugs? Now, put yourself in the other person’s shoes. What are they looking forward to about spending time with you? I’m willing to bet that the reasons your people love you have nothing to do with your appearance or your weight. So why is physical appearance often the first thing people comment on when there are so many more important aspects of who we are? Because diet culture teaches us that weight is an indicator of health or moral goodness (news flash: it’s not), people sometimes attribute deeper meanings to weight that are simply not true. These beliefs about weight are deeply ingrained in society. While there are ways you can fight diet culture, sometimes it can be helpful to accept that others are in different places in their personal journeys to freedom from diet culture. If someone judges you based on your weight – or any aspect of your appearance – that says more about them than it does about you. People may also bring up weight or dieting as a topic of conversation. If someone tries to talk about weight over the holidays, you can set a boundary and change the subject: “I’d rather not talk about weight. Have you watched any good TV shows lately?” Alternatively, if the thought of setting a boundary with the other person is daunting, you can start by setting an imaginary boundary. Imagine the other person trying to hand you all their body image angst. Say, “Thanks, but no thanks,” and hand it right back to them. Their overvaluation of weight is their work to do – not yours. Another way to practice acceptance is by using “maybe, maybe not,” a strategy from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). This response to eating disorder thoughts can help you accept uncertainty in a situation – for example, when you worry that someone might be judging you based on your weight. Maybe they are, maybe they aren’t. You can go on enjoying the holiday either way. Setting New Year’s Resolutions The new year provides an opportunity to reflect on our goals for personal growth. Unfortunately, diet culture has many people convinced that they should make weight loss their New Year’s resolution. Despite the fact that diets don’t work, the dieting and fitness industry profits enormously from weight-loss New Year’s resolutions when people sign up for new gym memberships and dieting programs every January. It can certainly be tempting to set a weight-loss resolution, especially when it seems like everyone else is doing it. Ask yourself: What are you hoping to gain by losing weight? Are you striving for happiness, confidence, health? Remember that your eating disorder will not bring you these things. But there are infinitely many New Year’s resolutions that have nothing to do with weight loss that might help you achieve these bigger-picture goals. For example, building mastery in a hobby can help boost your self-confidence (Kelly et al., 2020). Starting a daily mindfulness practice can lower your blood pressure and improve your cardiovascular health (Shi et al., 2017). Think about the values you want to live by and use them to inform your New Year’s resolutions. Practicing Self Compassion As the holidays approach, check in with yourself. What are you looking forward to in the holiday season? What parts of the holidays will be challenging? Make a game plan for the difficult moments. In the whirlwind of the holiday season, it may seem easier or safer to give in to your eating disorder thoughts. And if you do, have compassion for yourself. After all, a lapse is not a relapse. Be gentle with yourself, and treat this holiday season as a learning experience on your path to eating disorder recovery.

References Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8 Kelly, C. M., Strauss, K., Arnold, J., & Stride, C. (2020). The relationship between leisure activities and psychological resources that support a sustainable career: The role of leisure seriousness and work-leisure similarity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103340 Shi, L., Zhang, D., Wang, L., Zhuang, J., Cook, R., & Chen, L. (2017). Meditation and blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Hypertension, 35(4), 696–706. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001217 Written by Caroline Christian, M.S., Fourth Year EAT Lab Graduate Student Before reading this blog post, please first take a minute and think about what factors you believe influence how much a person weighs. ****** What was on your list? Was anything on your list related to food or exercise? Were these factors near the top of your list? In American society, as well as in many other parts of the world, there is a common belief that weight is determined almost exclusively by the amount and type of food consumed and amount and type of physical activity. While this is partially true (energy input and output from food and physical activity can impact how much you weigh) there are several, far more important factors that are often left out of the equation, which I will discuss later in this article. If you feel resistant to the idea that weight is more than diet and exercise, you are not alone. Many systems in our society are based on this belief, including virtually every diet and exercise plan that you see advertised today. And it is not an accident that this belief is so pervasive, as many corporations make a ton of money (over 70 billion dollars a year) from this commonly held belief (Marketdata, 2021). Industries that are benefitting include insurance companies, gyms, clothing stores, diet food companies, diet pill corporations, plastic surgeons, weight loss nutritionists, social media influencers, and many more. Do you know who doesn’t benefit from this belief? You. In fact, this belief contributes to many problems in our society. One of which is that this belief fuels stereotypes and discrimination towards people in larger bodies (Nadler & Voyles, 2020). For example, over one third of people in a larger body report being discriminated against due to their size, including being denied jobs and proper healthcare (Sikorski et al., 2016). Second, mental health concerns, including depression, negative body image, and disordered eating, are also linked to misinformation and myths about weight control (Carels et al., 2013; Hayward et al., 2018). Third, this belief leads people in all body types to spend excessive amounts of time and money on products and programs that don’t actually improve health or even influence weight in a lasting way. Beyond the fact that the weight = diet x exercise belief is harmful, this belief is not supported by science. Yes – food and physical activity can have an influence on weight, but these are two of many factors that determine weight (Bacon, 2011). Below, I talk about some of the other factors that are more important to influencing weight than food intake and exercise output.

These are just a few of many examples of how genetic and environmental inequities can influence weight and health; however, these few examples begin to highlight the sheer complexity of how weight can be determined by factors largely out of our control. Briefly, other important factors include

The media, gyms, and diet companies will continue to push the narrative that your weight is a direct consequence of your behaviors related to food and exercise. However, science supports that although a balanced diet and physical activity can improve health, they will not drastically change your weight from its intended set point. There are also numerous systemic and medical factors out of our control that prevent people from engaging in different health behaviors. Thus, it is important to practice compassion for yourself and others around weight. Even now, equipped with this information, you will likely continue to notice automatic judgment towards yourself and others, which is understandable given how engrained these messages are. AND we can do better. I encourage you to try to actively challenge these biases and false beliefs and to show acceptance and kindness to others, regardless of weight, to help dismantle the harm that weight misinformation and stigma can have. If you are interested in reading more about weight and health, I encourage you to explore the following resources.

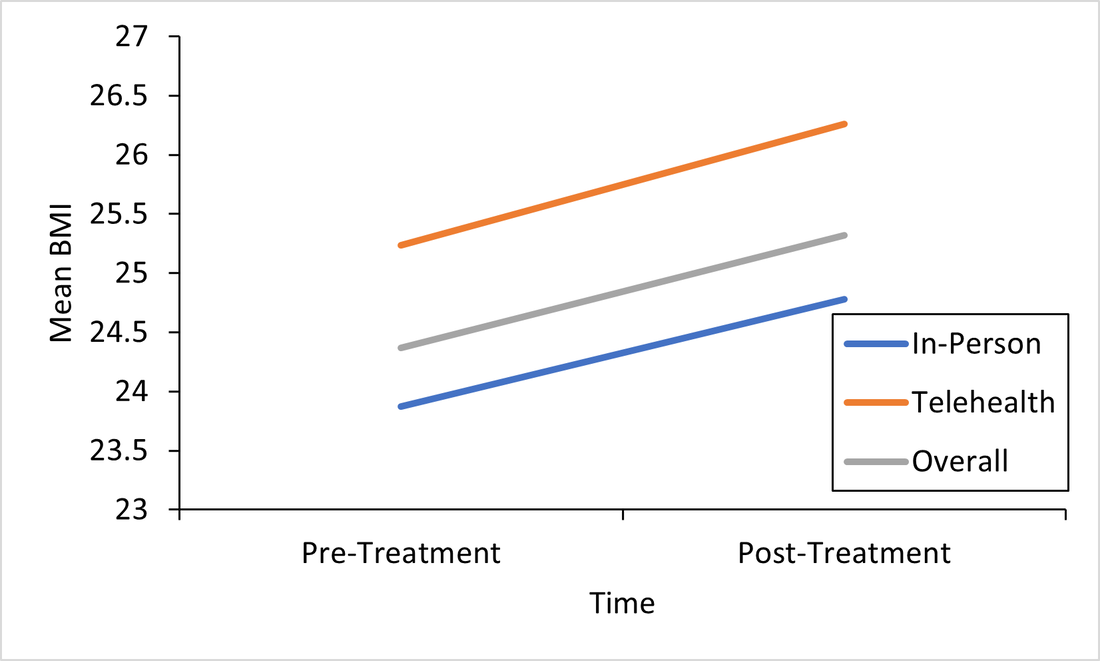

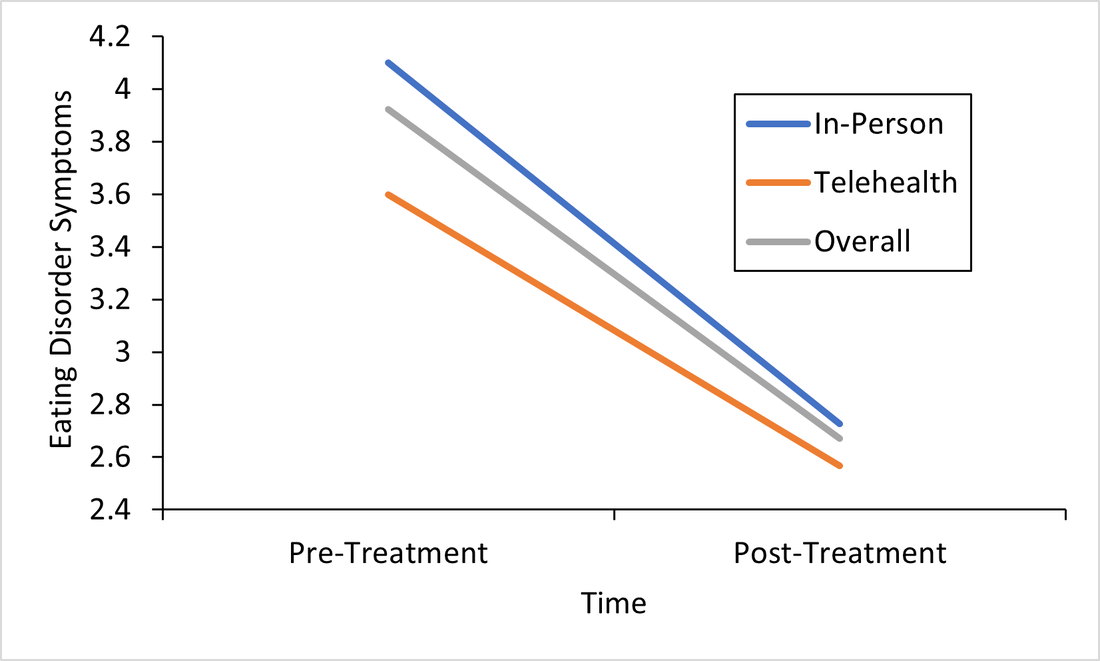

References: Bacon, L. (2011). Health at Every Size Revised and Updated. ReadHowYouWant.com. Carels, R. A., Burmeister, J., Oehlhof, M. W., Hinman, N., LeRoy, M., Bannon, E., Koball, A., & Ashrafloun, L. (2013). Internalized weight bias: Ratings of the self, normal weight, and obese individuals and psychological maladjustment. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-012-9402-8 Franklin, B., Jones, A., Love, D., Puckett, S., Macklin, J., & White-Means, S. (2012). Exploring Mediators of Food Insecurity and Obesity: A Review of Recent Literature. Journal of Community Health, 37(1), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9420-4 Goodarzi, M. O. (2018). Genetics of obesity: What genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 6(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30200-0 Hayward, L. E., Vartanian, L. R., & Pinkus, R. T. (2018). Weight Stigma Predicts Poorer Psychological Well-Being Through Internalized Weight Bias and Maladaptive Coping Responses. Obesity, 26(4), 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22126 Hewagalamulage, S. D., Lee, T. K., Clarke, I. J., & Henry, B. A. (2016). Stress, cortisol, and obesity: A role for cortisol responsiveness in identifying individuals prone to obesity. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 56, S112–S120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.domaniend.2016.03.004 Katsu, Y., & Baker, M. E. (2021). Cortisol. In Handbook of Hormones (pp. 947–949). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820649-2.00261-8 Lowe, M. R., Doshi, S. D., Katterman, S. N., & Feig, E. H. (2013). Dieting and restrained eating as prospective predictors of weight gain. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00577 Meyer, J. M., & Stunkard, A. J. (2020). Twin Studies of Human Obesity. In The Genetics of Obesity. CRC Press. Nadler, J. T., & Voyles, E. C. (2020). Stereotypes: The Incidence and Impacts of Bias. ABC-CLIO. Pickett, K. E. (2005). Wider income gaps, wider waistbands? An ecological study of obesity and income inequality. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(8), 670–674. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028795 Rose, K. L., Evans, E. W., Sonneville, K. R., & Richmond, T. (2021). The set point: Weight destiny established before adulthood? Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 33(4), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000001024 Roybal, D. (2005). Is “Yo-Yo” Dieting or Weight Cycling Harmful to One’s Health? Nutrition Noteworthy, 7(1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1zz4r4qk Sikorski, C., Spahlholz, J., Hartlev, M., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2016). Weight-based discrimination: An ubiquitary phenomenon? International Journal of Obesity, 40(2), 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.165 Staiano, A. E., Marker, A. M., Martin, C. K., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2016). Physical activity, mental health, and weight gain in a longitudinal observational cohort of nonobese young adults. Obesity, 24(9), 1969–1975. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21567 Wurtman, J., & Wurtman, R. (2018). The Trajectory from Mood to Obesity. Current Obesity Reports, 7(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0291-6 Responding to the Call for Accessibility: Breaking Down Recent Findings on Telehealth Vs. In-Person Eating Disorder Treatment During COVID-19 In Plain Language Written by Samantha Spoor B.S., Former Study Coordinator, Current PhD Student at University of Wyoming and Dr. Cheri A. Levinson, Ph.D. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unique challenges for those with eating disorders , particularly for those seeking support, and for providers who have had to adapt treatment delivery (e.g. virtual, hybrid; telehealth) to attend to barriers to treatment access associated with the pandemic. Most treatment centers responded to the pandemic by moving services either fully or partially online. However, we do not have a lot of science behind this transition. So we sought to change that. Members of our team at the EAT Lab recently published an article in partnership with the Louisville Center for Eating Disorders (LCED1) Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) evaluating outcomes for in-person versus telehealth treatment formats prior to and during the pandemic. In other words, we wanted to know, does telehealth intensive treatment (3 hours a day, 5 days a week) for eating disorders work? We expect that a lot of treatment moving forward will be delivered over telehealth, so it’s a very important question to answer! Read the full article here. To make these important telehealth vs. in-person IOP treatment findings from LCED accessible and understandable, this blog post replaces highly scientific language with a plain language summary of the findings below. We also provide additional comments about why these findings are important and what they show us about the ability of the eating disorder field to increase access to eating disorder treatment through the use of telehealth. Background: COVID-19 led to BOTH 1) more eating disorder symptoms and diagnoses in the general public and 2) worsening eating disorder symptoms for those who had already had an eating disorder (Phillipou et al., 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020). Further, the pandemic also led to increased barriers to accessing treatment, such that in-person treatment delivery became harder to implement while following public health guidelines, and posed a potentially higher risk of contracting COVID-19 for patients with EDs. Lastly, not a whole lot is known about delivering intensive ED treatment (particularly IOP) virtually! Purpose: We were interested in finding out whether moving the traditionally in-person IOP program to virtual in response to the COVID-19 pandemic would affect treatment outcomes. In other words, we were interested in the following questions: 1) Will eating disorder, depression, and anxiety symptoms decrease from admission to the IOP program to discharge, and 2) Will they decrease similarly regardless of if the treatment is in-person or fully online (telehealth)? Method: Participants (Who): Overall we had 93 participants with eating disorders go through the IOP program. About 60 patients received in-person (traditional) IOP treatment prior to COVID-19 and about 33 patients received virtual IOP treatment during COVID-19. These patients completed outcome measures of eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, and depression before and after treatment and agreed that we could use their data for research purposes. This sample of patients included individuals with Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge Eating Disorder (BED), Otherwise Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), and Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). In other words, patients with a wide variety of ED diagnoses participated in the research reported in this paper! Patients also reported a variety of other psychiatric diagnoses (in addition to ED diagnoses). Check out the article for figures and tables showing the breakdown of diagnoses! Procedure (How): Treatment for those enrolled in the IOP program prior to the COVID-19 pandemic participated in treatment on average for 10 weeks. All treatment was in-person. For those who enrolled during COVID-19, the same exact treatment format was implemented, but the delivery was completely online and virtual. Measures (What): For this study, we included measures of body mass index (BMI), and eating disorder, depression, and perfectionism symptoms as outcomes. You can read more about the specific scales we used in the full paper, but these were chosen because they are all important features of eating disorder treatment outcomes. For example, perfectionism has been shown to be intimately involved in eating disorders (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007). Analytic Approach: We also ran statistics to determine if there were any major differences in our outcome measures at the start of treatment (reminder: BMI & eating disorder symptoms, depression, or perfectionism symptoms) between those who started treatment prior to COVID-19, or after COVID-19 (there were a few - see below). Repeated Measures ANOVAS (Click to learn more) were used to assess if there were significant differences in outcomes for those who received virtual (during COVID-19) or in-person (prior to COVID-19) IOP treatment. This means- we tested are there differences in how well the IOP treatment works that depends on format (in-person or telehealth)? Results: The only significant differences between the virtual vs. in-person groups at the start of treatment were that the in-person group was more concerned than the virtual group was with two aspects of perfectionism that we measured: parental expectations and criticism. This result does not really mean much, but we always test for differences between groups when doing this type of research. Here are the important findings: BMI (weight): BMI increased overall and increased in both groups. See the Figure! The gray line are all the participants; the orange line are participants who did treatment via telehealth, and the blue is in-person. All the lines increase, which is what we want (for BMI specifically)! And, there were no differences between groups.  This is important because weight gain is a good sign that ED treatment is going well. Eating Disorder Symptoms: Eating disorder symptoms went down overall and went down in both the in-person and telehealth groups. Again, there were no differences between groups. This means that both treatment formats make eating disorder symptoms better! See Figure below, remember, the gray line are all the participants; the orange line are participants who did treatment via telehealth, and the blue is in-person. We won’t bore you with the additional figures, but you can find them in the full paper! We did find the same pattern for the rest of our outcomes: depression and perfectionism decreased similarly across treatment, regardless of whether patients received in-person or telehealth treatment. This is what we want to see!

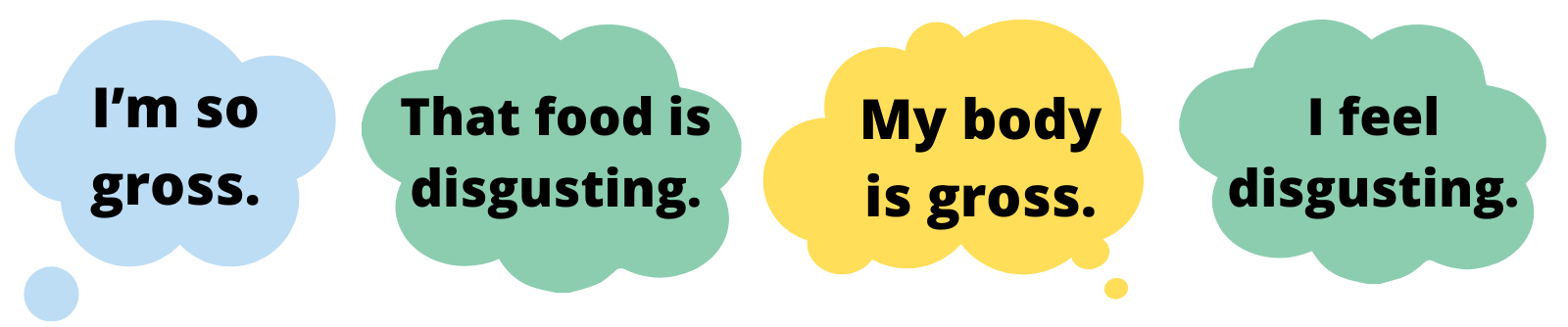

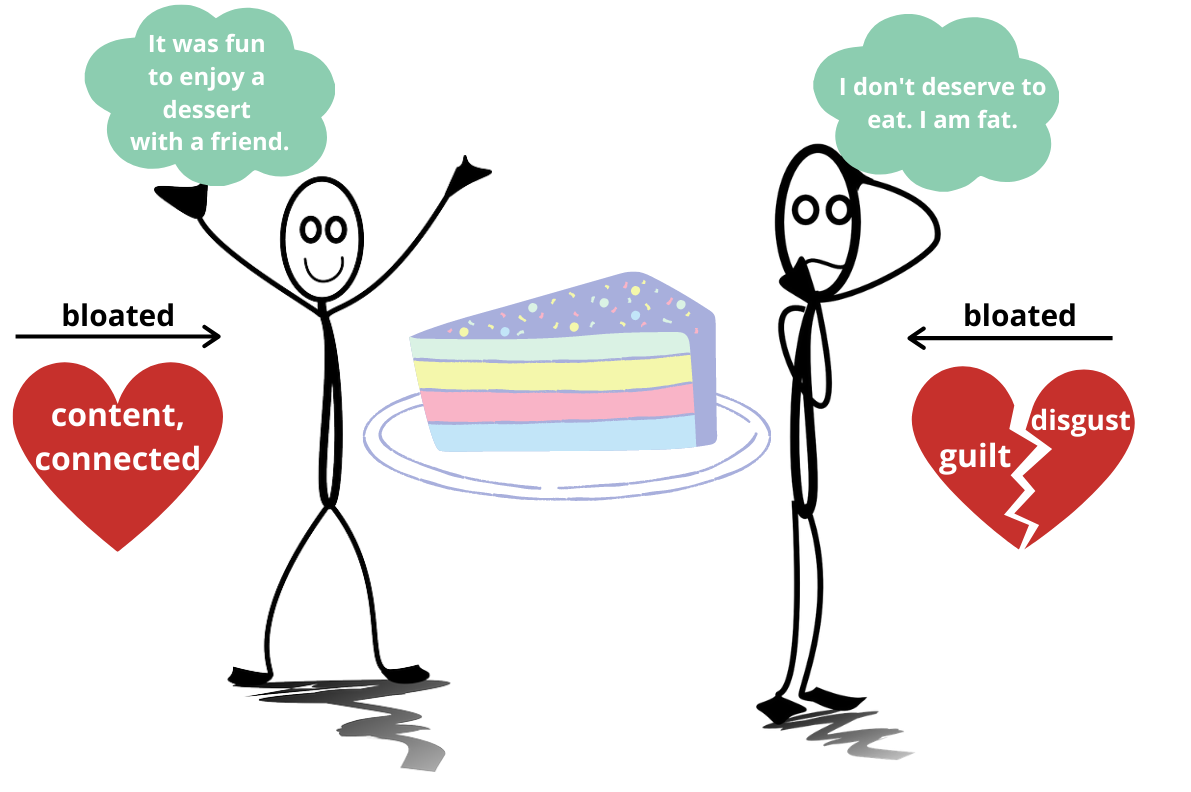

Conclusions: Eating disorder symptoms decreased. BMI increased. Depression and perfectionism decreased. This is what we want! And importantly , all outcomes were comparable across both groups. This means that telehealth team-based eating disorder intensive outpatient programming (IOP)is not only possible, but also may be equally as effective as traditional in-person team-based IOP treatment for eating disorders. At least, that is what we found in our sample in Kentucky. We hope to see more of this research throughout the U.S. in the future! There are a few limitations to consider regarding this research. Firstly, most of our sample was composed of white women, which, while representative of those who are most likely to access treatment, seriously limits the generalizability of our findings to truly representative and diverse populations of those with EDs. In other words, people of all races and genders can (and do) have eating disorders (Burke et al., 2020; Feldman & Meyer, 2007; Smolak & Striegel-Moore, 2001), and we have no way of knowing based on this study if our findings would apply to them, too. This is especially concerning given that those with marginalized identities, such as Black, Indiginous, and People of Color (BIPOC), and queer individuals, are frequently underserved in the eating disorder field. A few other important limitations include that we had a relatively small sample size (meaning having more people in the study would have increased our confidence in the findings), and that this wasn’t a randomized control trial (so we weren’t able to randomly select who got which type of treatment delivery, since we obviously did not predict the onset of the pandemic or offer any in-person treatment during COVID-19). Limitations considered, there are still HUGE implications for increasing treatment access to those who otherwise might not be able to receive in-person eating disorder treatment. If we can do eating disorder IOP as well virtually as in-person, then there is no reason that those who a) cannot afford transportation to treatment, b) live in rural areas, or c) simply live too far away from specialized treatment to commute, should be denied the opportunity. In this way, COVID-19 may precipitate long-overdue efforts to increase ED treatment access for underserved communities. Get Involved! Treatment Access Resource & Study: If you or someone you know has struggled to access high-quality eating disorder treatment for any reason at all, please consider checking out one of our EAT Lab partners, Project HEAL, for treatment access resources. Additionally, we are currently hosting a short, confidential online study (5-10 minutes long) in partnership with Project HEAL, to help the field understand the overlap and impact of various treatment access barriers for those with eating disorders. Please consider participating if you meet eligibility criteria outlined at the beginning of the survey and want to help. If you have questions about the plain language study summary (or the original article, linked above), please reach out to us via the comment board below on this page, and we would be delighted to correspond with you (or clarify anything better). And, if you’d like to see more content on the blog like this, let us know! Thank you! 1LCED is the only program in the state of Kentucky offering specialized IOP treatment for eating disorders. The center uses a multidisciplinary team-based approach to intensive eating disorder treatment, wherein psychologists, therapists, dieticians, and prescribers come together to treat each patient in an evidence-based and personalized manner. Citation: Levinson, C.A., Spoor, S.P., Keshishian, A.C., & Pruitt, A. (in press). Pilot outcomes from a multidisciplinary telehealth vs in-person intensive outpatient program for eating disorders during vs before the Covid-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders. References Bardone-Cone, A. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Frost, R. O., Bulik, C. M., Mitchell, J. E., Uppala, S., & Simonich, H. (2007). Perfectionism and eating disorders: Current status and future directions. Clinical psychology review, 27(3), 384-405. Burke, N. L., Schaefer, L. M., Hazzard, V. M., & Rodgers, R. F. (2020). Where identities converge: The importance of intersectionality in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(10), 1605-1609. Feldman, M. B., & Meyer, I. H. (2007). Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. International journal of eating disorders, 40(3), 218-226. Phillipou, A., Meyer, D., Neill, E., Tan, E. J., Toh, W. L., Van Rheenen, T. E., & Rossell, S. L. (2020). Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1158– 1165. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23317 Schlegl, A., Maier, J., Meule, A., & Voderholzer, U. (2020). Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1791– 1800. https://doi-org.echo.louisville.edu/10.1002/eat.23374 Smolak, L., & Striegel-Moore, R. H. (2001). Challenging the myth of the golden girl: Ethnicity and eating disorders. In R. H. Striegel-Moore & L. Smolak (Eds.), Eating disorders: Innovative directions in research and practice (pp. 111–132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10403-006 Written by Brenna M. Williams, M.S., Fourth Year Graduate Student I have a confession to make. I love animation. I’m talking Disney, Pixar, Cartoon Network, Japanese anime. All of it. I have loved animation since I was a little kid, and today as a 25-year-old PhD student, I continue to browse for the latest popular animated television shows on Netflix and HBO Max. I couldn’t tell you exactly why I love animation so much, but as an adult, I think it has a lot to do with the characters. I relate to and admire many of the characters as they develop. However, it is a privilege to relate to these characters, and I am privileged to have grown up with characters that share many of my identities and reflect my appearance and my beliefs. The world of animation is growing more and more diverse, with incredible animators from all backgrounds designing characters that reflect the variety of human beings in the world. This representation is important for children and adults alike. Positive representation (that is, portrayal of people in a positive and uplifting light) of individuals from marginalized communities, including people of color, women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and fat people can lead to increased self-esteem and decreased bias. Given how influential media is, positive representation in animation can have an impact on society. Shows like She-Ra and the Princesses of Power and Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts, with their diverse characters and cast, have already started making an impact. Given my specialty in eating disorders, I also think it’s important that animators design characters of all different body types. It’s also important that these characters’ bodies are portrayed positively, especially those in larger bodies. By showcasing characters of all body shapes and sizes, we can increase the representation of diverse bodies and challenge weight stigma and fatphobia. Throughout my adventures through animated shows, I have found some shows and movies that represent individuals with a variety of body types in a positive light. In this blog post, I share three of my favorites.  Steven Universe (2013-2019; ~10+ years old) Steven Universe is an animated television show that originally aired on Cartoon Network and is now available on Hulu or HBO Max. Steven Universe is a coming-of-age story about a young boy named Steven Universe who lives with the Crystal Gems in Beach City. The Crystal Gems are magical, humanoid aliens with special powers. This show explores themes of love, family, and relationships, and it features characters of all colors, genders, sexualities, and shapes and sizes. This series was created by Rebecca Sugar (she/they), who is both the first woman and non-binary person to independently create a series for Cartoon Network. The voice cast is also diverse, with women of color making up the majority of the main cast. Steven Universe is known for paving the way for many more recent LGBTQ+ series, and it focused on many LGBTQ+ themes prior to the SCOTUS ruling making same-sex marriage legal throughout the United States. Steven Universe was nominated for five Emmy Awards and is a beloved series by many. In 2019, a movie was also released, and a spin-off series, Steven Universe Future, was streamed from 2019-2020. I recently just started watching this series for the first time, and I am in love. Steven is a character unlike any other I have seen, and the mysteries of his family and the Crystal Gems has kept me watching for hours on end. This is definitely a series worth watching!  She-Ra and the Princesses of Power (2018-2020; ~8+ years old) She-Ra and the Princesses of Power is a reboot of the 1985 series She-Ra: Princes of Power. Available on Netflix, She-Ra and the Princesses of Power follows Adora, a teenager who finds out she can transform into the legendary heroine She-Ra, and her friends as they work to build the Princess Alliance and defeat the evil Horde. This series showcases characters of all shapes, sizes, colors, sexualities, and genders. Importantly, it includes a diverse cast as well. She-Ra and the Princesses of Power explores a variety of themes, including family, justice, and relationships and is best known for its exploration of LGBTQ+ themes. This one of my absolute favorites because of its character building and sense of humor. I shared this with my boyfriend and my roommate (who both loved it), and I recommend it to pretty much anyone who lets me.  Bee and PuppyCat (2013-Present; ~13+ years old) Bee and PuppyCat is an animated web series that follows Bee, an unemployed young woman, and PuppyCat, a mysterious creature that appears to be a cat-dog hybrid, as they work various temporary jobs together. The art style of this show is beautiful, and it has been compared to the work of Hayao Miyazaki. The characters are designed in a way that represents a variety of body types, and I especially love how Bee looks like an average woman in her 20s. The first season is available on YouTube, and season 2 is scheduled to stream on Netflix in 2022. There is still a great deal to learn about the characters and their backstories, but this storyline has become one of my favorites. I especially love PuppyCat, who is voiced by Oliver, a Vocaloid. I’m looking forward to watching the second season on Netflix, but in the meantime, I’ll keep watching the first season on repeat. I love animation. I love the art and the characters, and I especially love when the character design and development is focused on diversity. There are so many incredible series and movies out there that include main characters who represent many different backgrounds. I am looking forward to seeing more of these characters, and I hope that animators will continue to design characters that positively represent individuals of all body sizes. By Claire Cusack, M.A., Lab Manager, Incoming 1st year graduate student Ew. Gross. Ick. Yuck. People describe an array of things as gross, repulsive, or disgusting.  Disney Pixar's Inside Out, 2015 Disney Pixar's Inside Out, 2015 But what is disgust, and what does it have to do with eating disorders? At its base, disgust means “bad taste.” Disgust is a tool that may keep us alive by helping us to reject, spit out, and avoid food and substances may cause us disease and death (1). Disgust is a basic emotion characterized by a facial reaction (for instance, scrunching the nose), physiological sensation (e.g., nausea), and a visceral feeling of revulsion. As you’d expect, or have perhaps experienced, it is typically followed by avoidant behavior, such as moving backward, covering your nose, spitting something out, or closing your eyes. With this understanding, disgust may help us. For example, if you spit out poisoned food because it tastes bad, it may save your life! How does disgust run amok? Though disgust may serve as a protective function for our bodies, things can go awry in eating disorders (2,3) That is, your brain sends a false alarm that there is a threat, when in actuality there is none. Similar to anxiety, you may interpret a food as disgusting and overestimate the harm caused by it (4). Over time, your brain may pair a certain food with the feelings of disgust, and you may avoid foods that are not harmful but necessary for your survival. This pathway is difficult to change for a couple reasons: 1) Your brain’s resources are dedicated to prioritizing “safety,” and 2) Avoidance feels good (5).  What sets off the false alarm? This likely varies person to person, but there are some common triggers that may signal disgust. First, disgust is culturally bound (6) and tied to related ideas of morality (4). As a society, we decide what is “disgusting,” and when we engage in behaviors that elicit disgust, we then attach a good or bad value judgment to it. While fat is important for our survival, we may falsely learn that fat is bad or disgusting. So we may learn to believe that certain food or certain body sizes and shapes are good or bad due to us learning that fatness is disgusting (incorrectly; 7). Another player in setting off the disgust alarm are physical sensations (8-10). These could include feelings of bloating, tightness in stomach, nausea, or other unpleasant bodily sensations or experiences. These bodily sensations can be confused as feelings (11). Importantly, making sense of these sensations relies on our ability to detect and appraise sensations (12). For instance, for our survival, we first need to recognize a feeling and then evaluate it (e.g., harmful or safe). Below, we see how two different people can process the same event (eating cake) differently in terms of thoughts (it was fun vs. I shouldn’t have), emotions (connected vs. guilt), and physical sensations (e.g., feeling bloated). It can be challenging to integrate physical feelings, emotions, and thoughts. It’s especially difficult when you don’t trust your body (13). It makes sense to evaluate food as disgusting if you don’t believe your body will take care of you. However, food is only one aspect of disgust and eating disorders. Individuals with eating disorders find an array of things disgusting, such as food, weight gain, their body, but disgust can generalize beyond eating disorder content (14). The line between body and self can become blurred (15). In other words, individuals with eating disorders may also feel disgusted by who they are (8, 16). It’s so tempting to accept these thoughts and feelings at face value, but not all thoughts are true, in fact most are not. The bottom line: your body is not disgusting, and neither are you.

Ways to work through false alarm disgust: 1.) Identify what’s disgusting. Work with your therapist to identify and rank what is disgusting from least to most disgusting (17).You may work together to plan exposures to work through feelings of disgust. 2.) Learn your values. What are your values? Family, friends, school or work, spiritual growth, social justice, kindness, or maybe something else? You can write these down. Now, when you look at the disgusting list, do you believe the things on the disgust list above are disgusting or does your eating disorder? With this awareness, you may be able to make decisions that could still feel gross, but actually align with your values (18). 3.) Create opportunities for new learning. This suggestion builds on #1 and #2. If physical sensations such as drinking water, following your meal plan, eating foods that feel heavy in your stomach, or something else feels disgusting to you, and if they are a false alarm disgust, then press through and approach them. One way to approach false alarms is through interoceptive exposures. An interoceptive exposure is where you intentionally engage in activity that causes you to feel a particular sensation in your body. These exposures may help distress associated with your eating disorder (8,9,19). Let’s say feeling full disgusts you because you think that the sensation of fullness means you are gaining weight. You could drink water and sit with the bodily and emotional sensations that arise (or work with your therapist to do this). Mirror exposures may be useful for working through the body parts you find disgusting (20). This involves looking at the parts of your body that bring up feelings of disgust for you. These exposures can be practiced in therapy sessions and between therapy sessions. The goal is not to feel less disgusting but learn that you can handle this feeling. “You can be still and still moving. Content even in your discontent.” – Ram Dass 4.) Notice when the disgust alarm is false. Mindfulness exercises and meditation to increase awareness and accuracy of body signal interpretation (21, 22). For example, breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, or 5-4-3-2-1 (5 things you can see, 4 things you can touch, 3 things you can hear, 2 things you can taste, and 1 thing you can smell) can bring you to the present moment. Then, you may be better able to answer questions like, “Is this actually disgusting? Am I safe? Should I avoid this? Does that match my values?” 5.) You are more than your body. You may feel disgust in or about your body or body areas. This does not mean you are disgusting, because feelings are not always accurate. The feeling of disgust may be a false alarm, but it is felt as very real. Two truths can exist at once. A feeling (and/or a thought) is not a fact, so challenge these feelings/thoughts by asking yourself questions rather than accepting feelings as absolute truths. Is there evidence to suggest you are not disgusting? For example, did you help a friend? Or maybe you were kind to a coworker or peer? 6.) Fight fatphobia. Create new culture that values and celebrates all body sizes and shapes, including yours. Ask yourself, “Where did I learn this was disgusting?” If you’re interested in fighting fatphobia and learning more about diet culture, let us know by emailing canceldietculture@gmail.com – We have a new treatment study coming soon focused on this very issue! References [1] P. Rozin and A. E. Fallon, “A perspective on disgust,” Psychol. Rev., vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 23–41, 1987, doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.1.23. [2] T. Harvey, N. A. Troop, J. L. Treasure, and T. Murphy, “Fear, disgust, and abnormal eating attitudes: A preliminary study,” Int. J. Eat. Disord., vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 213–218, 2002, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10069. [3] B. O. Olatunji and D. McKay, Disgust and its disorders: Theory, assessment, and treatment implications. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, 2009, pp. xvii, 324. doi: 10.1037/11856-000. [4] J. M. Tybur, D. Lieberman, R. Kurzban, and P. DeScioli, “Disgust: Evolved function and structure,” Psychol. Rev., vol. 120, no. 1, pp. 65–84, 2013, doi: 10.1037/a0030778. [5] T. Hildebrandt et al., “Testing the disgust conditioning theory of food-avoidance in adolescents with recent onset anorexia nervosa,” Behav. Res. Ther., vol. 71, pp. 131–138, Aug. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.008. [6] P. Rozin and J. Haidt, “The domains of disgust and their origins: contrasting biological and cultural evolutionary accounts,” Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 367–368, Aug. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.001. [7] B. O. Olatunji and C. N. Sawchuk, “Disgust: Characteristic Features, Social Manifestations, and Clinical Implications,” J. Soc. Clin. Psychol., vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 932–962, Nov. 2005, doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.7.932. [8] K. Bell, H. Coulthard, and D. Wildbur, “Self-Disgust within Eating Disordered Groups: Associations with Anxiety, Disgust Sensitivity and Sensory Processing,” Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc., vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 373–380, Sep. 2017, doi: 10.1002/erv.2529. [9] J. F. Boswell, L. M. Anderson, and D. A. Anderson, “Integration of interoceptive exposure in eating disorder treatment,” Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract., vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 194–210, 2015, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12103. [10] M. Plasencia, R. Sysko, K. Fink, and T. Hildebrandt, “Applying the disgust conditioning model of food avoidance: A case study of acceptance-based interoceptive exposure,” Int. J. Eat. Disord., vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 473–477, 2019, doi: 10.1002/eat.23045. [11] O. G. Cameron, “Interoception: The Inside Story—A Model for Psychosomatic Processes,” Psychosom. Med., vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 697–710, Oct. 2001. [12] S. S. Khalsa et al., “Interoception and mental health: A roadmap,” Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 501–513, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004. [13] T. A. Brown et al., “Body mistrust bridges interoceptive awareness and eating disorder symptoms,” J. Abnorm. Psychol., vol. 129, no. 5, pp. 445–456, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1037/abn0000516. [14] L. M. Anderson, H. Berg, T. A. Brown, J. Menzel, and E. E. Reilly, “The Role of Disgust in Eating Disorders,” Curr. Psychiatry Rep., vol. 23, no. 2, p. 4, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01217-5. [15] J. Moncrieff-Boyd, S. Byrne, and K. Nunn, “Disgust and Anorexia Nervosa: confusion between self and non-self,” Adv. Eat. Disord., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 4–18, Jan. 2014, doi: 10.1080/21662630.2013.820376. [16] J. R. Fox, N. Grange, and M. J. Power, “Self-disgust in eating disorders: A review of the literature and clinical implications,” in The Revolting Self: Perspectives on the Psychological, Social, and Clinical Implications of Self-Directed Disgust, P. A. Powell, P. G. Overton, and J. Simpson, Eds. London: Karnac Books, 2015, pp. 167–186. [17] R. M. Butler and R. G. Heimberg, “Exposure therapy for eating disorders: A systematic review,” Clin. Psychol. Rev., vol. 78, p. 101851, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101851. [18] C.-Q. Zhang, E. Leeming, P. Smith, P.-K. Chung, M. S. Hagger, and S. C. Hayes, “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Health Behavior Change: A Contextually-Driven Approach,” Front. Psychol., vol. 8, 2018, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02350. [19] E. E. Reilly, L. M. Anderson, S. Gorrell, K. Schaumberg, and D. A. Anderson, “Expanding exposure-based interventions for eating disorders,” Int. J. Eat. Disord., vol. 50, no. 10, pp. 1137–1141, Oct. 2017, doi: 10.1002/eat.22761. [20] T. C. Griffen, E. Naumann, and T. Hildebrandt, “Mirror exposure therapy for body image disturbances and eating disorders: A review,” Clin. Psychol. Rev., vol. 65, pp. 163–174, Nov. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.08.006. [21] J. Gibson, “Mindfulness, Interoception, and the Body: A Contemporary Perspective,” Front. Psychol., vol. 10, 2019, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02012. [22] P. Lattimore, B. R. Mead, L. Irwin, L. Grice, R. Carson, and P. Malinowski, “‘I can’t accept that feeling’: Relationships between interoceptive awareness, mindfulness and eating disorder symptoms in females with, and at-risk of an eating disorder,” Psychiatry Res., vol. 247, pp. 163–171, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.022. Committing to Recovery: How Recognizing Your Values Can Help You Recover from Your Eating Disorder3/10/2021 By Brenna M. Williams |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed