|

Written by Cheri A. Levinson, Ph.D.

First, I need to disclose how my perspective is formed, based in both lived and clinical experience and scientific training. I am an eating disorder therapist and researcher. My livelihood is dedicated to alleviating suffering for those who have eating disorders, both through the development of new and better treatments and through treating patients with a variety of eating disorders across the weight spectrum. Perhaps more importantly, is that I am also a reformed dieter. I spent my life from the ages of 19 to 30 on diets, constantly trying to lose weight, beating myself up about how “fat” I looked, and bouncing back and forth between a “normal*” weight and “overweight.” I now know because of my scientific and clinical training that I should have been diagnosed with atypical anorexia nervosa (read about A-AN here), but I never was despite seeing several therapists for anxiety and stress throughout this time. Why? Most likely because I was never officially “underweight” or if so, not for very long. I have not made this public knowledge until now. Now, at 39 years old, I am considered “obese” by outdated, yet widely-referenced medical standards. I am not on a diet, I eat a wide diversity of foods that I enjoy and savor, I’m happy, healthy (yes you can be healthy at any size!), and I love my body (truly- it happens!). My body is currently growing my third baby girl and I am grateful every day for what my body does for me. Like so many people with similar lived experiences, I would need a book to document my life’s journey finding body acceptance (someday!), but that is not the point of this post. The point is to reflect on the growing trend happening in the weight management area with the use of Ozempic (semaglutide, wagovy, glp1s). This reflection is informed by both my professional and personal experience. My current opinion on Ozempic is that I am highly skeptical regarding its use for weight loss. I would not use it. In fact, I would stay far, far away from Ozempic. I expect it will cause a lot of damage before we have conclusive data one way or the other. The history of the weight loss industry tells us that routinely, when one approach (e.g., Weight Watchers, Bariatric Surgery, Intermittent Fasting, etc.) either goes out of style or is debunked, another will replace it. Each of these methods have left harm in their wake, especially for those with eating disorders (read more here: article by Levinson et al.). I sincerely hope that I am wrong about Ozempic and it does not turn out to be the latest “fad diet” and can instead be a helpful medication (for health [not weight loss] purposes). I would love to find an easy cure for the endless negative thoughts present in eating disorders. But history has yet to find a ‘magic’ bullet for mental illness and it will take a very, very lot of well-conducted research, including assessment of long-term potential harms, to convince me that Ozempic is not the latest weight-loss fad (again, this is not a comment on its use for other areas, such as diabetes). Second, I want to thank Dr. Cynthia Bulik for her thoughts here: Reflections on Writing About Ozempic for “Science” | Exchanges (uncexchanges.org), many of which have inspired my thoughts expressed below. She writes about many pros and cons of the rise of Ozempic, many of which I will discuss here. I also want to be clear that this post concerns Ozempic for weight loss and in particular the impact it may have on eating disorders. I am not familiar enough with the diabetes, substance use disorders, or other areas that Ozempic may be used for to comment on those areas. The Eating Disorder Landscape. Eating disorders are at an all-time high in terms of prevalence rates. It is estimated that up to 20 percent of Americans will have an eating disorder during their lifetime. Yearly economic and loss of well-being costs are estimated in the 400 billion range. As a mother of two (almost three!) young girls, what scares me the most is the growing trend that life-threatening eating disorders are starting at age 8 or 9. Eating disorders are not getting better – in fact, they are getting worse. They kill someone every 52 minutes. At the same time, diet culture, anti-fat bias, and fad-diets (with many names) are widely promoted in society. Most women (up to 95%) report being dissatisfied with their bodies and wanting to change them. Foods are labeled as unhealthy, (e.g., “fattening,” “empty”) and immoral (e.g., “bad,” “naughty,” “guilty pleasures”), when in reality, food has no morality and what is deemed “healthy” is subjective. Medical doctors widely promote the message that to be healthy you must be a certain weight, when weight actually tells us very little about the health of an individual. Countless pediatricians suggest that children should lose weight (a shared experience by many individuals who later develop eating disorders) during a period when bodies are supposed to be growing and expanding. Through research, clinical practice, and lived experience, the connection is clear: Dieting, restriction, food rules, food labeling, and weight bias are all major players in the development and maintenance of eating disorders in all ages. Propagation and Advertisements of Ozempic for Weight Loss. Dr. Bulik starts her post by mentioning the advertisements that are currently bombarding users of Facebook urging them to try Ozempic to lose weight. I think we need to take a minute and reflect on how truly alarming it is that we are all being flooded with advertisements for this new drug. I too have seen ad after ad for Ozempic pop up across multiple of my social media accounts. I am currently in my second trimester of pregnancy and Facebook is suggesting that I start taking weight loss medication. If that does not ring as truly devastating to you, well, let me spell it out: I am growing a human being in my body, and taking weight loss medication would be harmful to both me and my unborn child. Now, I know that if I am seeing Ozempic ads and Dr. Bulik (a leading eating disorder expert) is seeing Ozempic ads, our patients with eating disorders and many people with eating disorders who do not know or recognize that they have eating disorders, are seeing these ads. And to date, there is no data out there suggesting that these medications would be helpful for those with eating disorders (at least 20 percent of the population at some point during their life). Indeed, most eating disorder experts are strongly warning against the use of these medications given the potential for harm (any negative energy balance or restriction can set off or re-trigger an eating disorder). As Dr. Bulik writes, perhaps to me, the most compelling statement in her blog post, “The second issue relative to eating disorders is the potential for abuse. As an eating disorders specialist, this scares me enormously. I cannot overemphasize the vigilance that clinicians and carers should maintain about the misuse of these drugs. It is not a stretch to anticipate them having serious if not fatal consequences in very underweight individuals.” Though I would argue this applies to all individuals with eating disorders regardless of if one is “underweight” or not, especially given that most research finds that those at higher weights have as bad or worse medical complications from their eating disorder, go unrecognized (see above re lived experience), and are often unable to access care. Regardless of size, these medications have huge potential to become another harmful way to propagate eating disorders. Eating Disorders Get Quiet When Weight Loss is Happening. We need to consider the long term. Eating disorders are loud. They scream at you to not eat, to eat as little as possible, that you are bad, ugly, fat [note I identify as midsize/fat- it is not a bad word], and worthless. People with eating disorders will do most anything to quiet those thoughts. They are uncomfortable. Guess what quiets the thoughts? Losing weight. When weight management researchers report that their “weight loss” treatment improves eating disorder symptoms in the short-term, they are not wrong. Because in the short-term, weight loss quiets the thoughts, which quiets the other extreme attempts (e.g., behaviors) at weight loss. The problem is the long-term maintenance of a harmful cycle. This phenomenon has been shouted loudly from those with lived experience, and researchers need serious thought and work to better document this cycle. Because weight comes back or thoughts come back when you are no longer *losing* weight. It is impossible to lose weight forever without dying. Perpetual weight loss is however, the goal of the eating disorder. Dr. Bulik discusses that there are reports that Ozempic has “a profound cognitive effect that it is like changing the channel on a TV. The soundtrack of their minds completely changes, eliminating the constant food noise that fed their eating disorder.” I would love for this to be true. But I will remain unconvinced until I see long term data showing that Ozempic can quiet eating disorder thoughts. Because in the short term, of course it quiets thoughts. This is the same mistake weight management researchers make when they interpret a short-term decrease in eating disorder symptoms as a positive. They are only capturing part of the harmful cycle. Which leads us to the harms of weight management treatment… Harms of Weight Management Treatment and Weight Stigma. The harms of weight management treatment in reference to eating disorders and weight stigma are just beginning to be documented. I am not going to go into an overly-exhaustive explanation of these harms because they were discussed by myself and colleagues here. Suffice it to say it feels like fighting an uphill battle. As soon as there is some recognition of the harms that are caused by weight stigma and the harms of focusing on weight in medical and psychological treatments, a new ‘shiny thing’ comes along promising a new way to lose weight, and **this time** it works (no, really! If you squint hard enough the data is so promising)! Unfortunately, all the prior instances of promising new ways to lose weight have failed and left many individuals suffering. This is why I, and many eating disorder researchers, therapists, and those with lived experience, are so wary. What harm will Ozempic leave as its legacy? Time will tell. The Role of Individuals Versus Systems. And Access. A very important point about Ozempic is the current food environment we live in and how that impacts outcomes. Issac Ahuvia and Dr. Jessica Schleider wrote a very recent and important article pointing out the fact that interventions that focus on individuals instead of recognizing that the system is actually the problem can promote individual and structural harm. Fatphobia, weight stigma, and the weight loss industry embody the very definition of a systemic problem that is attempted to be treated in an individual manner. Though individuals have very little control over their weight, they are continuously made to think they are to blame (personally, I think people of all sizes are beautiful and that we should not change this- but our society thinks differently). We know that things like poverty, food insecurity, food desserts, and mass production of profit-making foods, contribute to high weight. Yet, we try to change individuals. Ozempic is another attempt at individual change. If we really wanted to improve health (note the distinction between weight and health) we would put efforts into addressing poverty, food insecurity, food desserts, and regulating profit-based food and health companies. Part of the major problem here is access. Poverty precludes access to diverse foods. If you are worried about whether you can feed your family for the next week, you don’t have the luxury of choosing between more expensive produce and lean protein. And why do we think that Ozempic will change these facts? It will continue to be accessible to those with resources and those without resources will not have access. Continuing to perpetuate a harmful cycle on an individual level without addressing the structural systems that are actually causing the problem. Another band-aid on a wound without treating the infection. Lifelong Medication Use. When you stop Ozempic the weight comes back. What happens when you become pregnant? Breastfeeding? Need cancer treatment? Or any other reason out there that medications must stop. I would like to see answers to this before I would ever recommend someone start a lifelong medication. Health at Every Size. Dr. Bulik also thoughtfully points out the fact that Ozempic may have an impact on the growing movement toward health at every size and fat positive groups that are pushing society to look differently on how we view weight. She writes, “Is there still a place for these groups, or will the widespread use of these medications actually lead to a new flavor of discrimination, “Why would someone CHOOSE to remain fat when these medications are widely available?” This is where I start to see a very large problem and gap between how society views fat and how people in these groups view fat people. To me, fat is a body descriptor. Just like thin, brown eyes, long hair, etc., and all of these descriptors are beautiful. They are all expressions of our human bodies that lead us through life. Someone who is fat may be medically healthy. Someone who is thin may be medically unhealthy. Just as though we cannot tell who has an eating disorder by viewing their body, neither can we tell if someone is “unhealthy” by viewing their body. This is the vision these groups promote. I highly agree with this vision and think it leads to healing and both mental and physical health. So why someone would “CHOOSE” to remain fat is not the problem, nor will it ever be relevant. Its highly dystopic to think we will ever live in a world where everyone’s bodies are the same size and fatness does not exist. I certainly would not want to live in a world with no body diversity. Instead, we should be asking, how do we better recognize medical problems and treat those? Can Ozempic improve those regardless of what happens with weight? If we were prescribing Ozempic to improve actual health metrics, I would not be writing this opinion piece. Weight is the Wrong Target Mechanism. Which brings me to the statement I keep repeating over and over: Weight is the wrong target mechanism. In the mental health field when we develop treatments, we have to first show that a ‘target mechanism’ that is related to our outcome of interest, is impacted by the treatment we are developing. Weight is not the mechanism by which health is impaired. As stated above, you can be thin and have poor health. You can be fat and have poor health. What we actually need is to focus on the underlying mechanisms that lead to poor health if we want to improve health. Not weight. This is probably another blog post in itself. The main point is, weight is a problematic focus, whether that focus is with Ozempic or any other form of intervention to ‘so called’ change weight. Side Effects. I haven’t delved into this and won’t go into detail. But this really needs to be paid attention to. I’ll just leave you with a post from a mom’s group that I am in. A mom in the group asked for experiences with Ozempic and the overwhelming response was negative. This is not an eating disorder, body positive etc group- it is a general moms group. Most of the time I see a lot of pro-diet culture in this group. But here is a sampling from one mom in response to this issue, “Don’t do it! Yes I lost weight-but I started getting dizzy and passing out almost daily before stopping and developed POTS. I stopped and my POTS went away but my stomach is all messed up, my period is irregular, and I am constantly constipated. If I could go back in time I would say no. The things I am dealing with it are not worth it.” Would you willingly take this medication? Do you know what else causes dizziness, constipation, and passing out? Not eating regularly (i.e., an eating disorder). What would Really Solve the Issue. Systemic change. Combatting poverty. Regulating Big Pharma and For Profit food and health companies. Universal healthcare. Medical professionals treating everyone equally regardless of their weight. Getting rid of constant societal messaging that we should diet, limit foods, and lose weight. Accepting bodies of all size. Stopping our overfocus on appearance, what someone looks like on the outside, and anti-aging. Promoting food variety and regular eating. Pushing for joyful movement. Practicing body gratitude. All of these things would actually improve the health of our society. I have little hope a little pill (or shot) will be the trick. *weight categories are always in quotes because they are based on the highly flawed body mass index as a metric References

Thank you to Dr. Irina Vanzhula, Dr. Hannah Fitterman-Harris, and Samantha Bedard for providing feedback on earlier versions of this post.

1 Comment

Written by Allison Grady, B.A. – Study Coordinator This blog post is intended for young adults feeling discouraged that their college years are “nothing like what’s on social media." The American college experience is something that’s often glamorized, idealized and celebrated as a cultural rite of passage; a period of four years filled with self-growth, strong friendships, gameday weekends and a newfound sense of independence that leads many to proclaim that the years spent at university are “some of the best years of your life.” Such sentiments are supported through videos and images of college students plastered on social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, most notably contributing to trends such as #RushTok, a TikTok trend in which incoming first-year college students post “outfit of the day” videos and document the fashionable process of “rushing” for placement in a sorority in some of the country’s most prestigious Greek Life environments (1). Such social media content appears polished, filtered, and “perfect:” painting a mirage of what college is “supposed to look like” that may be strengthened through storytelling and the fond memories shared by college students’ senior loved ones and counterparts. So much of what we see advertised about the college experience appears through a rose-colored lens.Rarely do we hear about how difficult it is to balance your personal life and studies, to show up to class and excel on exams whilst simultaneously spending quality time with friends, working, competing in a sport, and/or fulfilling other important life obligations. Rarely is it acknowledged that in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, among college-aged populations, rates of depression, alcohol use disorder, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder were significantly increased in comparison to such rates pre-pandemic (2). Rarely is it discussed how the prevalence of clinically significant eating disorders is higher among college-aged individuals in comparison to the general population, with 20% or less of those students having received treatment for their eating disorder (3). The transition to college is perceived as rose-colored and extravagant, yet the reality is, for many students, such advertised experience could not be farther from the truth, and there is always more to someone’s storythan what meets the eye. During the transition to college, young adults may instead experience an increased vulnerability to disordered eating and exercise behaviors and cognitions (4). Further, common college pastimes, such as involvement in a sorority, is correlated with worse weight-related outcomes (5), and college athletes are at a higher risk for body image disturbances and disordered eating behaviors, based on their motivation for sport participation (6). For many students, college doesn’t look like it’s “supposed to,” as seen on social media or in the movies; nor does it resemble what many graduated acquaintances fondly recall in their stories of the “glory days.” Remember that people are always excited to share the “glamorous” parts of their lives, and are typically less willing to share the parts of life that aren’t as “pretty.” Just because your experience doesn’t match what others are presenting to the outside world doesn’t mean your story is of lesser value. There is always more to someone’s story than what meets the eye. Here’s the bottom line: College is tough. Nobody talks about the challenges you face when you begin your studies as an undergraduate, and this is a frustrating sentiment. Remember that this phase of your life holds value, but it is by no means “the best.” There is so much more to life.

In the meantime, here are some ways you can help prioritize your mental health while earning your undergraduate degree:

Extra mental health resources for college students The Mental Health Coalition: College Mental Health Toolkit https://www.thementalhealthcoalition.org/college-mental-health-toolkit/ National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI): Mental Health in College https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Kids-Teens-and-Young-Adults/Young-Adults/Mental-Health-in-College References

Written by Kimberly Osborn, M.S.W. - Lab Manager This blog post is targeted toward individuals struggling with eating disorders and their loved ones. Although it is a part of human nature to compare ourselves and to even try to outperform other people, especially in things that are important to us, Western culture often encourages and reinforces harmful and disruptive forms of comparison and competition. We are often inundated with societal and interpersonal messages that encourage us to push ourselves to extremes, whether that is extreme productivity, extreme standards for success, or even extreme health and weight-related behaviors. We are also repeatedly told that our success and self-worth depend on how well we perform compared to others, and this is reinforced throughout our lives at school and work, in relationships, and even within ourselves. Considering this, it is unsurprising that many of us struggle with social comparison or feel the need to prove our worth by competing with others in life domains that are important to us, such as academics, work, relationships, physical appearance, etc. Comparison and competition can be helpful in some circumstances such as helping us recognize areas in our lives where we would like to improve or by offering examples about how to perform better in domains that are important to us. However, when our self-worth is based on where we stand within a particular social ranking, especially one that is wholly dependent on achievement or other factors outside of our control, it can impact our relationships with other people and even ourselves (1). When comparison and competitiveness are core components of a relationship, they often become less genuine and can even cause harm to us and those we care about. These dynamics can also make us feel worse about ourselves and our abilities and cause us to engage in behaviors that are unhealthy for us. Trying to “prove” we are worthy by pushing past our own limits in order to outperform other people often leads to frustration, feelings of unworthiness, and even burnout. While there is a lot of variety in the ways people compare and compete with others, health-related behaviors, weight or shape, and food intake seem to be particularly common areas of comparison and competition in our culture (2). Unfortunately, we live in a fat-phobic society where thinness is glorified and obsessive efforts to achieve these ideals are reinforced throughout our lives. It is unsurprising, therefore, that many people engage in direct comparison and competition about what they eat and how they move their bodies to determine their self-worth and relative social standing (3). These dynamics are certainly harmful to everyone by contributing to unhealthy and disruptive patterns of relating to others and ourselves, but they can be especially harmful to individuals struggling with eating disorders (EDs; 3) Body- and food- related comparisons can negatively impact the way individuals suffering from EDs view themselves, their illness, and even their recovery. People with lived experience of EDs often report feeling “not sick enough” compared to other people with EDs, and this can lead to feelings of shame and frustration, as well as a reluctance to seek help (4). For some people, this can result in attempts to become “sickest” by losing more weight or by increasing the number or severity of ED behaviors. Although not all people with EDs struggle with these interpersonal dynamics, there are many environments where they do occur, especially in spaces where people with disordered eating or EDs come together, both online and offline. For example, research suggests online ED communities (including both recovery-oriented and pro-ED spaces) can become competitive (5). Explicit examples of these types of interactions include overt competitions related to weight loss or the number of calories eaten, which are often observed in spaces where recovery is not considered a priority, such as pro-ED sites. However, this dynamic often occurs much more subtly, especially in spaces that endorse explicit orientations toward recovery, such as ED recovery accounts on social media and among peers receiving ED treatment. On the surface, these spaces often appear to be wholly supportive of recovery and free from the types of competitive attitudes and behaviors seen in other ED spaces. Yet, there are several indications that individuals may be attempting to gauge their social standing within these communities based on current or previous illness ED severity. Examples include:

People with EDs report that comparison based on shape or weight, ED behaviors, or illness severity can result in a felt need to engage in more extreme weight loss attempts or ED behaviors to ensure their illness is at least as “severe” as their peers, possibly as a way to reduce fears or concerns about the validity of their ED (6). The use of extreme ED behaviors and medical consequences can be viewed as ways to increase one’s social standing among others with EDs, even when these dynamics are not explicit or not fully conscious to the individual. Often, people struggling with EDs report desires not only to be as sick as their peers but sometimes express desires and attempts to be thinner or “sicker” than others. This may be the result of fearing they are failing in their ED, and subsequently failing as a person, if they do not demonstrate the highest levels of self-control or the most discipline in their self-imposed and increasingly rigid food and body rules. Shame and embarrassment frequently accompany these feelings and behaviors as many people with EDs deeply care about others and may not be naturally inclined to compare and compete with others. If you are someone with a current or past ED and have experienced thoughts or feelings related to these topics, it is important to remember you are not alone, and it doesn’t make you a bad person. It is human nature to compare ourselves with others and it is normal to want to be considered valuable and respected by others. Unfortunately, EDs tend to overshadow other, more important, aspects of ourselves, including our values, hobbies, and other things that positively influence the way we think about ourselves and the world around us. As a result, an ED diagnosis or ED behaviors often come to feel like the most important part of who we are and even lead us to base our identity and self-worth almost entirely on how “successful” we are at losing weight or engaging in ED behaviors. And as we discussed before, humans naturally look to others to determine how we are performing within a certain domain, so comparisons and competitive attitudes with other ED sufferers make intuitive sense, although these dynamics can be extremely detrimental to us and those around us, which begs the question: What can we do about it?

Extra Resources on Comparison and Competitiveness Psychology Today: The Best Anorexic https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/starving-the-banquet/201109/the-best-anorexic Why do we Compare Ourselves to Others?: The Emily Program https://emilyprogram.com/blog/why-do-we-compare-ourselves-to-others/ References

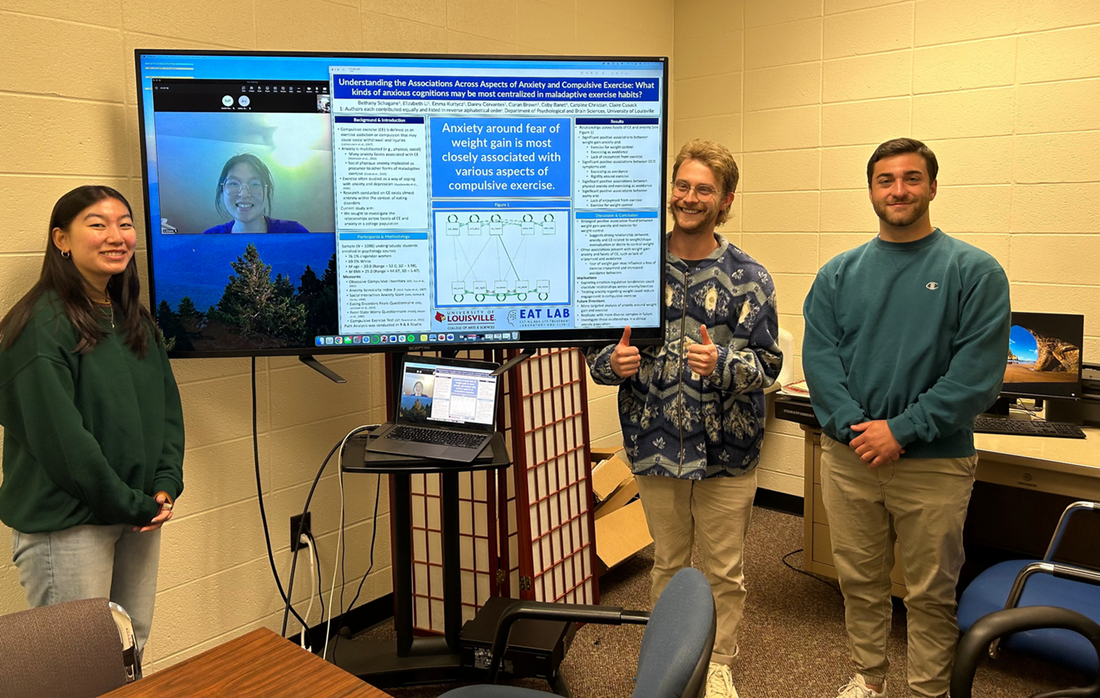

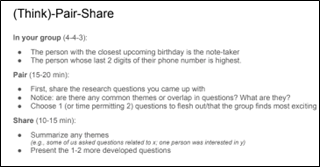

Written by Claire Cusack Meaningful undergraduate research opportunities can be hard to come by. For instance, it’s often the case that students are already in the lab several semesters before pursuing questions, which raises issues of equity (e.g., what type of student can continually volunteer 8-10 hours a week), in the honors program (again, partially related to systemic factors), and the reality is there are typically not enough mentors to supervise independent research for all research assistants. In this blog post, I explain how we created student-led research experiences at scale using approaches from course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). Within classroom settings, CUREs provide enriching research experiences for more students, and here we applied these concepts to our large group of undergraduate researchers in our group. I hope that those interested in mentoring student-led research may adapt this course to their own labs. Materials can be accessed here. This Google drive contains the Fall 2022 and Spring 2023 syllabi, slides, example code, and their posters. The EAT Lab and RAs: Who We Are and Context Currently, the EAT Lab consists of 5 graduate students, 5 post-doctoral fellows, 3 lab managers, 5 study coordinators, a data manager, 23 research assistants at various levels of training (undergraduate students, individuals who are post baccalaureate, master’s students, doctoral students), and our PI Dr. Cheri Levinson. RAs are matched with a graduate student, post-doc, or study coordinator who serve as their primary supervisor. They volunteer up to 10 hours a week, which includes unsupervised time where they complete tasks for their supervisor, an individual supervision meeting, and one hour in the RA lab meeting. Often, students come to the lab hoping to gain research experience to complete a capstone requirement, to help clarify career goals, or augment their materials for PhD and MD programs. This RA meeting will be the focus of this blog post. All RAs are expected to attend RA meeting. The goal of this meeting is to provide RAs with the experience of being in a research lab environment conducting team science. In previous years, they’ve looked like journal clubs, introducing aspects of the research process conceptually, and/or professional development focused meetings. Creating the Course This year, I decided that RA meetings had to look different for the following reasons: 1) I noticed that some RAs had been there longer than I have and likely sat through the same meetings (e.g., what is a literature search); 2) the meetings, while undoubtably helpful, were relatively didactic and passive (e.g., listening to a lecture; responding to discussion questions); and 3) I wanted students to leave this year feeling like they had created knowledge and actively contributed to science. As such, I designed RA meetings as a CURE. CUREs replace cookie-cutter lab courses that have pre-determined answers with student-led inquiry. That is to say, CUREs allow students to learn to do actual science of asking and answering unknown questions all within the bounds of a dedicated class. CUREs have been shown to facilitate STEM retention (Eagan et al., 2013) and be particularly helpful for individuals with minoritized identities continuing in STEM (Espinosa, 2011). Importantly, inquiry-based learning is a pedagogical approach that centers student-led questions and problem-solving, which can be implemented through CUREs (Aditomo et al., 2013). Inquiry-based learning providers students with ownership over their own learning and is associated with increased engagement and academic achievement (Buchanan et al., 2016). I designed this CURE based on Bangera and Brownell’s (2014) assertion that a successful CURE builds self-esteem, encourages confidence, teaches knowledge about research and research skills, and unveils the hidden curriculum and academic norms (Bangera & Brownell, 2014). Ultimately, my goals were to:

Preparation To apply research skills, I designed the course so that RAs worked in small groups on different research projects. The steps I took before the semester started included: 1) Get approval and get data. As mentioned, the structure of RA meetings vastly differed from prior years, and we needed data. Dr. Levinson allowed us to use lab data for this purpose. 2) Make it feasible. While I wanted to show as apply as many skills as possible, I also had to think about what was feasible. For example, in a pre-semester survey, many RAs expressed interest in R programming language. Though introducing R may be doable, cleaning a dataset in R and coding from scratch could take a whole semester alone. I cleaned the datasets over the summer so that RAs could “run” with them in the fall. Similarly, I guided questions to ensure students applied statistics they may have been introduced in an introductory statistics course rather than more advanced analyses. 3) Get help. Caroline Christian, 5th-year doctoral candidate in the EAT Lab, agreed to help me. I was absolutely thrilled she came on board because she is truly brilliant, a phenomenal person to work with, and really, a great person just to be around! Working with Caroline made implementing this course much easier. Additionally, Madison Hooper, a doctoral candidate at Vanderbilt University and EAT Lab collaborator, provided support in supervising one of the research groups. I also gathered syllabi from my undergraduate mentor, Dr. Jennifer Hughes, who implements CUREs at Agnes Scott College. 4) Think about timing. Because RAs volunteer and are busy humans outside of the EAT Lab, I wanted to restrict the time they worked on their projects to within the time of our lab meetings. I started with end goals and designed the course backwards accordingly. How We Approached Our Goals  Figure 1. Constructs. Fall 2022 Slides “Wk2.TestableQPt1” Figure 1. Constructs. Fall 2022 Slides “Wk2.TestableQPt1” 1) Co-Create a Learning Ecosystem. To co-create a learning ecosystem, we strove to increase participation and create a climate where all students felt their contribution was necessary. As with many group dynamics, it is common for more confident members to take up space. In developing group activities, we were intentional in which student would share. Sometimes, this decision was random (e.g., “the youngest water sign will share”); other times, we asked a student who maybe hadn’t spoken recently. Additionally, when students asked questions, we took them seriously and praised the ask. We tried to give students opportunities to hear from each other and value diverse perspectives. Lastly, we left 2 meetings each semester for an RA-driven topic, meaning they chose what they wanted to discuss. These topics were decided through brief surveys and group discussion. In this way, students played a role in deciding the course content. The topics they decided on included CVs, career paths, and how to talk about their eat lab experiences (in cover letters, statements, interviews). Even when topics could have been more passive and didactive, we continued to stress active learning and participation throughout these sessions (e.g., each RA had to peer review each other’s CVs). 2) Foster a sense of community and belongingness. Building community and a sense of belongingness takes time. We approached this goal by starting the meetings with check-in questions that were not related to their work or academics. After one meeting, I felt confident that they could plan a horror movie watch party, something that could not have been said about these students last year! We asked about their lives/things they had mentioned in previous meetings. We brought in snacks. An RA left anonymous feedback for office hours, so I created office hours. When students shared about their own experience or how their culture viewed the topics we were discussing, we actively listened and validated their insight. I think of this goal largely as the “in between moments.” I loved coming into the lab and seeing them connect, even outside of RA meetings. Importantly, the group research projects acted to build community as well as they required students to work together and depend on each other. 3) Apply research skills. Students can volunteer in many labs without actually learning how to ask a research question, much less test one. If we want people to stay in STEM, we need to provide them with real opportunities to practice STEM. In one of our early meetings, I presented students with a list of constructs and asked them to reflect on what interested them (e.g., the “think” of a think-pair-share activity). Briefly, in the fall semester, we formed research groups, decided on questions, discussed open science principles, and introduced R and data visualization. Students read articles, created a collective literature search, and presented short summaries on their articles (RAs who attended asynchronously sent in videos of their lightning talks). In the spring semester, we focused on interpreting analyses, identifying the main findings, making a poster, writing an abstract, and reflecting. Lessons Learned 1) Be flexible (and over-budget time). We revised the syllabi several times based on the pace we accomplished learning objectives. There were points where I accepted that we may not finish posters. I thought that it was worth spending more time on topics to deepen learning than it was to rush an outcome (i.e., poster). Some topics took more time than I anticipated (literature search, R, and creating posters), others less (writing an abstract). Sometimes, our check-in question took longer than I had allotted. I decided to take this time because I thought it was important in approaching the goal to build community. 2) It is difficult to design active learning with RAs attending in-person, virtually, and asynchronously. We tried to generate activities for asynchronous RAs and sent video recordings of meetings, and frankly, it was challenging. Even if we did have activities for them so that they could contribute, I worried about group cohesion. I asked RAs for suggestions on solutions, and they decided to create slack channels and groupme’s for their research groups. I hope that helped, but honestly, I do not think that this course (at least the way I designed it) worked well for asynchronous students. 3) Let go of perfection. The point of the course was to grow in scientific knowledge and build community. Were the literature reviews thorough? No, but they got experience of reading critically, synthesizing articles succinctly, and integrating multiple articles. Can they code in R after this course? Some RAs took it on themselves to deep dive into R and can! Others, maybe not. That said, when new RAs joined in the Spring semester, my heart swelled as I heard existing RAs explain R and orient new students to the language and software. The analyses may not be publication quality, but they did learn to interpret output. The posters could use more edits, and we opted for more general feedback than nitpicking. It was tricky to balance breadth and depth but letting go of perfection helped. Outcomes At the end of the semester, I asked RAs about their experience. When asked about their experience in RA meeting, one student wrote: “I loved them! It was a lil hard, ESPECIALLY as the semester went on, to wake up that early for a meeting so I would maybe suggest keeping them at least very slightly later if at all possible, but that's just personal preference, I know others may prefer morning's. Besides that, they were always a super welcoming environment and I felt like, as we had more meetings together, we were able to get at least a little closer toward an enjoyable conversation among peers rather than a formal meeting. And of course, learned a lot across completing our poster and discussing topics in the realm of professional development.” Students described that knowing they were working toward a poster made sticking through some of the hard parts (e.g., the literature search; R) more meaningful and motivating. Many reflected that as time went on, they felt as though they came together as a group. As one of our goals was to foster community, I was so happy to hear this feedback. Below are excerpts from end-of-course anonymous student feedback.  Last but not least, their research. One group examined the relationship between anxiety and exercise; another group investigated the associations among emotional regulation, perfectionism, and eating disorder symptoms in adolescents, and the third group investigated the relationship between weight bias internalization and eating disorder symptoms among across demographic variables. It was a joy working with them on their research questions and to grow into myself as mentor. A year is a long time to stick with something, and I am so proud of their grit and sustained engagement. In our second to last meeting of the Spring semester, we held an EAT Lab Symposium. We invited grad students, post docs, and study coordinators to join our RA meeting where they presented their work. One group also presented their work at the University of Louisville’s Undergraduate Research Showcase. Their posters can be accessed here. I am so grateful for our RAs and treasure the time spent with them this year. When I reflect on the mentors and mentorship I’ve received over the years, especially as an undergraduate student, one of the most impactful things for me is that I felt as though my mentors believed me. They took my goals seriously. They showed up for me when I needed help. They cheered for me. I hope to give RAs a fraction of the support and grace I’ve received from my past and current mentors. Students have consented to their photos being shared on our website, twitter, and this blog post. References

Aditomo, A., Goodyear, P., Bliuc, A.-M., & Ellis, R. A. (2013). Inquiry-based learning in higher education: Principal forms, educational objectives, and disciplinary variations. Studies in Higher Education, 38(9), 1239–1258. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.616584 Bangera, G., & Brownell, S. E. (2014). Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experiences Can Make Scientific Research More Inclusive. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(4), 602–606. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-06-0099 Buchanan, S., Harlan, M., Bruce, C., & Edwards, S. (2016). Inquiry Based Learning Models, Information Literacy, and Student Engagement: A literature review. School Libraries Worldwide, 22(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.29173/slw6914 Eagan, M. K., Hurtado, S., Chang, M. J., Garcia, G. A., Herrera, F. A., & Garibay, J. C. (2013). Making a Difference in Science Education: The Impact of Undergraduate Research Programs. American Educational Research Journal, 50(4), 683–713. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213482038 Espinosa, L. (2011). Pipelines and Pathways: Women of Color in Undergraduate STEM Majors and the College Experiences That Contribute to Persistence. Harvard Educational Review, 81(2), 209–241. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.2.92315ww157656k3u Caroline Christian, Ph.D. Student in the EAT Lab Every parent wants to help their child lead a happy and healthy life. For parents of children in larger bodies, this can feel like a difficult challenge. Many parents are left scrambling, without much guidance, to find answers. The question, “How do I help my child be healthy?” may lead to a google search, with search terms like, “diets for kids” and “child weight loss.” This quick search can then lead to a rabbit hole of ads and articles about dieting and weight loss products for kids, most of which are aimed at “helping” parents and kids in larger bodies. However, lurking behind the guise of health are pages of products selling thin- (rather than health-) focused weight loss programs to hopeful parents, and even some targeted directly to young children. What is not reflected in these ads, however, is the immense short- and long-term harm of dieting in children, specifically diets that involve restricting calories or nutrients to promote weight loss. We live in a diet culture, which means we live in a society that values thinness and equates thinness to health, morality, and beauty. Diet culture promotes losing weight at all costs, even health. Diet culture messages about weight loss are not limited to google; they are all around us, and all around our kids. Now, more than ever, parents must critically consume information about dieting and weight loss and consider how we share these messages with our children. A recent scientific review suggests that children’s negative beliefs about larger bodies are influenced by many sources, including peers, parents, teachers, and media use.(1) Such harmful beliefs about weight can begin by around age 3, and dislike of one’s own body often begins around ages 5-7.(2) As young children are exposed to negative messaging and stereotypes about larger bodies, restrictive dieting behaviors become more prevalent. In one study, approximately 60% of 6-13 years old have engaged in restrictive dieting and in a national epidemiological study, approximately 20% of middle school children have used extreme weight-control behaviors, such as skipping meals.(3) Importantly, dieting is associated with many negative short- and long-term health outcomes. First, although it may sound counterintuitive, research shows that dieting for weight loss in children predicts overeating and weight gain.(3,4) This is because restrictive diets trick the body into thinking there is limited access to food. In order to protect against starvation, the body lowers metabolism, redirects energy, and stores as much energy as possible to try to gain weight.(5) Cycles of restrictive dieting, especially from a young age, raises the body’s natural healthy weight and increase risk for serious health issues, including heart disease and type II diabetes.(6) All bodies respond to dieting this way; however, children are still developing physically and cognitively, which adds additional dieting risks. For example, if a child is not receiving adequate nutrition due to restrictive dieting, the body will start redirecting nutrients to the vital organs, which leaves limited energy for growth, puberty, and brain functioning. Children who are on diets, even children in larger bodies, may experience stunted growth and delayed puberty.(7) Additionally, children who are on restrictive diets may have difficulty with learning, memory, and attention, due to the brain not receiving the nutrients needed for proper functioning and development, leading to challenges at school and socially.(8) Beyond these physical and cognitive effects, dieting and diet culture messages can take a great toll on children’s and teens’ mental health. Studies suggest that dieting during childhood or adolescence is one of the most important predictors of the onset of eating disorders during this stage.(9) Additionally, experiencing and internalizing diet culture messages is associated with high levels of depression and anxiety and low self-esteem.(1) As children start receiving messages that thin = healthy, good, or beautiful, they often start to view their own body more critically. Children and adolescents who do not meet this thin appearance ideal may feel as though they are the opposite – unhealthy, bad, or ugly – leading to higher depression and anxiety symptoms. In fact, children who have experienced weight-based discrimination are almost twice as likely to engage in self-harm or suicidal behaviors compared to their peers.(10) Given the risks associated with dieting and diet culture for children in larger bodies, it is especially important for parents, caregivers, and teachers to take an active role in helping promote healthy behaviors in children, without the negative consequences of dieting. Below are some strategies supported by science:

1. Remove value labels on foods. One of the most prevalent diet culture beliefs is the idea that some foods are “good” and other foods are “bad.” Most restrictive diets and weight loss plans, including those designed for children, classify some foods, like pizza, ice cream, and pasta, as “bad.” These messages are quickly internalized by children, who may begin to avoid many “bad” foods, greatly limiting their food variety, and leading to feelings of shame and guilt if they do eat these foods. It is natural for children to enjoy sweets. Incorporating sweets in moderation into a child’s diet can help reduce cravings for and overeating on these kinds of foods. Discussing how different foods make the body feel can also help children build intuition about how to best fuel their body. For example, a child may quickly recognize that a donut for breakfast everyday may not give them the lasting energy to pay attention at school. Listening to their body’s needs is a helpful way for children to start making decisions about food, compared to making decisions based on what the scale says. 2. Model healthy eating and body image behaviors. It is no secret that children learn from their parents. Disordered eating in children is directly related to parents’ disordered eating and conversations with parents about eating.(12) When children hear adults saying things like, “Oh, I get to eat this because I worked out this morning,” “I’m so hungry, but I can’t eat because I am already at my points for today,” and “I shouldn’t wear this, it makes me look fat,” it is natural for them to start believing the same things about themselves. These statements put children in a box of feeling like they need to earn their food, restrict their food, and shrink their body. Even if parents are doing everything to feed their child a balanced and nourishing diet, children can still develop unhealthy beliefs about food and their body if parents’ model restrictive eating or negative body talk about themself. 3. Teach effective emotion regulation skills. One major cause of unhealthy eating patterns is using food to cope with emotions. While emotions are a natural part of eating, if over- or undereating are one of the only coping skills that a child has, it can lead to a dependence on food to feel good. Parents and teachers have a unique opportunity to help children respond to emotions effectively from a young age. Rather than responding to children’s emotions with food-related rewards or consequences, like “You can get a lollipop if you stop crying,” other strategies may be more helpful and sustainable. For example, parents may help children with taking deep breaths, communicating about their emotions, and practicing basic mindfulness. You can read more about emotion regulation for kids here. 4. Diversify experiences around food. Diet culture thrives on the belief that food can be used and manipulated to change one’s weight or body shape. However, the reality and complexity of nutrition is much richer and more enjoyable. By involving children in various parts of the process around food, like taking them to the grocery store or local farms, watching programs like Waffles & Mochi, and letting them help cook dinner, children can begin to see food as more than calories. These experiences also help kids learn about and understand how nutrition can be rewarding. If you are interested in reading more about the empty promises of dieting and diet culture or how to better support children with developing healthy eating and body image, below are resources for continued reading and learning. Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight How to Raise a Mindful Eater: 8 Powerful Principles for Transforming Your Child's Relationship with Food Why Diets Make Us Fat: The Unintended Consequences of Our Obsession With Weight Loss Kids, Carrots, and Candy: A Practical, Positive Approach to Raising Children Free of Food and Weight Problems Your Dieting Daughter...Is She Dying for Attention? References: 1. Puhl RM, Lessard LM. Weight Stigma in Youth: Prevalence, Consequences, and Considerations for Clinical Practice. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(4):402-411. doi:10.1007/s13679-020-00408-8 2. Jensen M. Body Dissatisfaction and Weight Bias in Children. Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. Published online May 1, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.26076/a9d6-14f6 3. Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38(2):112-122. doi:10.1002/eat.20158 4. Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation Between Dieting and Weight Change Among Preadolescents and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):900-906. doi:10.1542/peds.112.4.900 5. Rose KL, Evans EW, Sonneville KR, Richmond T. The set point: weight destiny established before adulthood? Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2021;33(4):368-372. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000001024 6. Roybal D. Is “Yo-Yo” Dieting or Weight Cycling Harmful to One’s Health? Nutrition Noteworthy. 2005;7(1). Accessed August 31, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1zz4r4qk 7. Campbell K, Peebles R. Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents: State of the Art Review. PEDIATRICS. 2014;134(3):582-592. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0194 8. Datta N, Bidopia T, Datta S, et al. Meal skipping and cognition along a spectrum of restrictive eating. Eating Behaviors. 2020;39:101431. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101431 9. Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J, Story M, Haines J, Eisenberg M. Obesity, Disordered Eating, and Eating Disorders in a Longitudinal Study of Adolescents: How Do Dieters Fare 5 Years Later? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106(4):559-568. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003 10. Sutin AR, Robinson E, Daly M, Terracciano A. Perceived Body Discrimination and Intentional Self-Harm and Suicidal Behavior in Adolescence. Childhood Obesity. 2018;14(8):528-536. doi:10.1089/chi.2018.0096 11. Robinson E, Sutin AR. Parents’ Perceptions of Their Children as Overweight and Children’s Weight Concerns and Weight Gain. Psychol Sci. 2017;28(3):320-329. doi:10.1177/0956797616682027 12. Berge JM, MacLehose R, Loth KA, Eisenberg M, Bucchianeri MM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Parent Conversations About Healthful Eating and Weight: Associations With Adolescent Disordered Eating Behaviors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(8):746. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.78 Written by Sara Clark  If you have heard any of these comments during pregnancy, you are not alone. As a mom of 3, I have been there and heard all these things multiple times throughout every single one of my pregnancies, and I hated it every time. Every comment left me feeling incredibly self-conscious and embarrassed; like there was something wrong with me or how I was choosing to manage my pregnancy. Everyone seemed so excited to appraise my pregnant body for changes, and no one really bothered to pay attention to the person, and their feelings, behind the bump. The more comments I got, the more it stung. While these comments are often meant to be a way to ask about your pregnancy, and most of it is intended to be lighthearted, sometimes it can be really insensitive! Managing your own conflicting feelings about your changing body and pregnancy can be difficult enough without the added stress of heading into a social event knowing you will hear these things over and over again. So, what are we supposed to do about the frustrating, confusing, wonderful, and sometimes anxiety inducing feelings we have over our changing body in pregnancy and on top of that, handle navigating social situations with them? First of all, take a deep breath and know that you are not alone in these feelings, studies show that pregnancy is a time for increased anxiety especially over all of the physical changes that are experienced. What you are feeling is totally normal. Something that has been shown to help manage any new or old anxious feelings is to practice mindful self-compassion. Mindful self-compassion is learning to view yourself, your experiences, and your feelings with a more open and forgiving heart. This might be something that you are familiar with; the idea of mindfulness is not exactly a new concept. This philosophy has been used in Buddhism for thousands of years. However, more recently researchers are taking these philosophies and making them much more accessible in daily-life practices and formal meditations. According to Dr. Kristin Neff there are 3 main components to engaging in self-compassion; they are self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. By introducing these into your everyday life and activities, you are giving yourself skills to learn to manage any emotions that come up when people comment on your changing, pregnant body and increase your wellbeing. Mindfulness

Self-Kindness  Image by Cathy Thorne https://everydaypeoplecartoons.com/ Image by Cathy Thorne https://everydaypeoplecartoons.com/ Imagine you’re enjoying yourself at a party and someone says to you, “Oh wow! Haven’t you had that baby yet!” And suddenly you feel really angry, and then you immediately feel guilty for feeling angry at this person for simply trying to make conversation. What do you do?! First, good job using mindfulness and acknowledging how you feel! Now is a good time to practice some self-kindness. Self-kindness implores us to treat ourselves with the kindness and understanding that we would a close friend or family member. While that might seem simple enough, sometimes it can be really difficult! Take a moment to think about the last time you made a big mistake, were the comments you made to yourself very kind, or were they critical? Would you say those same things to a friend if they made a mistake? Contrary to popular belief, we tend to treat others with more kindness than we do ourselves. Imagine a friend is retelling this story to you from their point of view, would you criticize them for feeling angry in the moment? Probably not, as a friend you would most likely offer a kind, sympathetic ear and comfort your friend. Self-kindness can look different for different people in this situation. It might look like simply getting through the conversation as cordially as possible and then taking a moment to yourself. Something that helped me move through these events was to have a few phrases that helped empower me, while creating my own self kindness support and boundaries with others. Some of my favorite phrases that I liked to use were; “I know! Isn’t it amazing, I’m growing a whole human being!” “Thanks for your concern but my body is no one’s business but my own” “My doctor tells me that we are fine and perfectly healthy” “I don’t know what you mean? I’m not pregnant?!” but only if you are feeling extra, ;-) Common Humanity The final pillar of mindful self-compassion is Common humanity. Common humanity is taking a moment to realize you are not alone. For example, you are not alone in your feelings, and you are not the only pregnant person to ever have these feelings. Sometimes, being human can be incredibly isolating. We can trick ourselves into thinking that no one could possibly understand us. That’s not true! As someone who has experienced pregnancy, I can absolutely relate to all these frustrating confusing feelings. The next time you’re at your Obstetrics office take a moment to look around the waiting room. I guarantee at least one (most likely all) of those other expecting parents have heard or thought negative comments about their changing pregnant body. Odds are they felt exactly like you did when you heard intrusive comments about your pregnant body. You might be the only pregnant person in your family or friend group and so finding common humanity might feel difficult. To help build common humanity, try to seek out positive pregnant parent groups. These groups can be found on social media, “preparing for baby” classes at your hospital, local Le Leche League chapters, or even local prenatal exercise classes. The most important thing is that you find a place where you feel most comfortable, supported, and can find common humanity with other pregnant families.

Just like you are practicing ways to respond to your new baby’s needs through learning things like diapering, feeding, and soothing skills, mindful self-compassion skills are essential for learning how to take care and support yourself. So, when you find yourself on the receiving end of any of these “intrusive pregnancy comments” take a moment to remember we tend to treat others with more kindness and understanding than we treat ourselves. Rather than becoming frustrated with yourself for not loving every part of pregnancy and feeling personally attacked or resentful about the comment, remember that you are human and what you are feeling is normal and valid. Finally, we are worthy of kindness, even if in the moment it is only coming from ourselves, taking a minute to reflect on this can ease some of the most stressful moments in pregnancy. If you are interested in more mindful practices, please visit Dr. Kristin Neff’s website, they have many free and wonderful resources, to help you practice mindful self-compassion during and after your pregnancy. https://self-compassion.org/ Resources for local pregnancy support in Kentuckiana: https://uoflhealth.org/services/womens-health/center-for-women-infants/ https://nortonhealthcare.com/services-and-conditions/obstetrics-and-gynecology/services/pregnancy/during-pregnancy/parent-classes/ https://www.baptisthealth.com/louisville/patients-and-visitors/community-classes-and-support-groups/classes-and-programs/maternity-classes/ https://www.mamatomama.us/programs https://louisville.momcollective.com/pregnancy/pregnancy-infant-support/ Rowan Hunt, MS and Hannah Fitterman-Harris, PhD Despite their depiction in media, we know that eating disorders are about more than food, weight, and bodies. Often, it’s easier to talk about these things than what is underlying the eating disorder: emotions. Emotions are so human; everyone experiences them. However, sometimes feeling emotions (especially emotions like anger, sadness, and anxiety) can be uncomfortable. In the face of this discomfort, it’s easy to get caught up in trying to avoid the emotions. This also seems to be true in the case of eating disorders. Individuals sometimes use eating disorder behaviors to try to reduce or avoid negative feelings.(1) Research has shown that people who had difficulty recognizing and regulating emotions were also more likely to have eating disorder symptoms.(2) Additionally, those with eating disorder symptoms were less likely to use helpful coping strategies to manage their emotions – like accepting their emotions, thinking differently about a situation to decrease negative emotions, or problem-solving – and were also more likely to use unhelpful strategies such as rumination (continuously focusing on a negative thought or situation), avoiding emotions, and suppressing emotions.(2) To summarize, individuals with eating disorders tend to feel more negative emotions, less positive emotions, and tend to have a harder time sitting with those emotions or using helpful coping strategies. This tendency towards emotions like sadness, anger, and anxiety can prompt individuals with eating disorders to turn to eating disorder behaviors to distract from or relieve unpleasant emotions. However, we know that emotions are like signals – and when you ignore the message that they are trying to send to you, the alarm just gets louder. As a result, these unpleasant emotions can rebound and come back stronger – thus driving an unfortunate cycle of more eating disorder behaviors. So, how do we get out of this cycle? Research suggests that teaching individuals to use more helpful (and less unhelpful) ways of regulating their emotions could help to improve eating disorder symptoms.(2) One place to start is by learning the purpose of your emotions. It may feel like our emotions (again – especially emotions like anger, sadness, and anxiety) don’t serve any purpose but to make us feel bad. However, we know that all emotions (even the “bad” ones) do something for us. By learning the purpose of our emotions, it can be easier to accept them (or at least tolerate them). “Emotions are not problems to be solved. They are signals to be interpreted.” – Vironika Tugaleva So why do we have emotions? What do they do for us?

In summary, emotions communicate important information. When we use our emotions as signals and respond to them with curiosity rather than fear or avoidance, they can tell us a lot about what’s going on in the world and what we need in any given moment. The next time you’re feeling sad, angry, or fearful, instead of trying to stuff down the emotion try thinking about what that emotion is trying to tell you! References

By Abigail McCarthy, EAT Lab Research Coordinator

Learning or noticing that a friend or family member is struggling with an eating disorder can be devastating. The signs might be blatantly obvious– your loved one could:

Or, especially at first, the signs might be more subtle– you could’ve noticed that your loved one is:

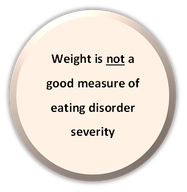

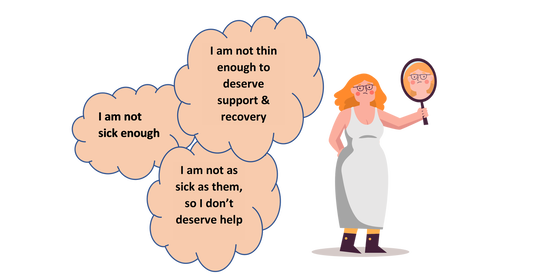

It’s important to remember that 90% of people with an ED have normal body mass index, so often it is hard to visually tell if someone has an eating disorder. They might need more rest than usual to support their new “healthy” habits or could’ve finally reached their goal weight or shape. You might notice the distress on their face when they look in the mirror, but you think they look amazing. Dealing with an ED is a hard battle that nobody should have to fight alone. Here are ways you can actually make a difference: 1. Do your research and find a professional for support. It’s important to have education regarding eating disorders, but remember you are NOT their dietician, therapist, psychologist, or psychiatrist. Provide yourself with the knowledge to recognize the signs of an ED or a medical emergency as directed to by professionals. Here is some helpful and trustworthy information with a help hotline: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/what-are-eating-disorders 2. Encourage your loved one to seek help. This could look like starting with a licensed counselor or seeking specialized eating disorder treatment. For more information, visit: What is ED treatment?: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/treatment Treatment near you: https://map.nationaleatingdisorders.org 3. Try not to take things personally. If your loved one seems defensive or angry while denying that they are putting themselves at risk, remember that this is the ED talking– not your child, friend, sibling, parent, or cousin. Find a different outlet to express the anger you have towards their ED. Respond with love, empathy, and “I” statements. Do NOT confirm their ED behaviors to avoid conflict, remove yourself from the situation if you feel yourself doing so. More information on “I” statements: www.nationaleatingdisorders.org 4. Remember to take care of yourself too. Use self-care if you feel yourself becoming stressed or overwhelmed. Your mental health can be affected if you only prioritize another person. Self-Care information: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/caring-for-your-mental-health 5. Remember they need to choose recovery for themselves. Avoid drawing attention to their disordered eating behaviors in front of others, keep these conversations private. Avoid forcing them to eat or face feared foods or asking them why they just “can’t” eat, these will likely make things worse. 6. If you and your loved one are minors, tell someone. If you worry your friend has a hard home life, and could be unsafe if you notified their parent, reach out to a school psychologist, guidance counselor, or other trusted adult. You can also reach out to the helpline on the National Eating Disorder Association website. You can’t handle this on your own, and neither can your loved one. Eating Disorder Helpline: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/help By Kimberly Osborn, Lab Manager in the EAT lab When considering whether you should seek help for your eating disorder, do you have thoughts like: Maybe you believe that your suffering is less valid because you are not at a certain weight or don’t engage in certain behaviors. If this describes you, you are not alone!  Despite the extraordinary physical and psychological suffering caused by these deadly illnesses, many people have trouble believing their struggles are valid regardless of the severity of their eating behaviors. [1,2] These beliefs often discourage people from reaching out, which prolongs suffering and causes further physical and psychological harm. Although these thoughts are very common among people with eating disorders, research shows that weight is often not associated with the severity of a person’s eating disorder or the level of impairment they are experiencing. [3,4] The fact is that severity of your eating disorder cannot be measured simply by the number on a scale or body mass index because it is a mental disorder. This means that you cannot tell how much a person is struggling or how malnourished they are just by looking at them. Did you know that people in larger bodies can have severe and serious restrictive eating disorders? This is because weight is impacted by many factors outside of food intake and exercise behaviors, such as genetics, hormones, age, etc. In fact, most people with eating disorders are not in the “underweight” category.[5] “But I have normal lab results, so I am not “sick enough” to get help.” This is also a misconception! Lab results provide a snapshot of some aspects of your health in that moment, but they do not show the full story about the negative impacts the eating disorder has on your physical and mental functioning. Studies show that people with severe and life-threatening eating disorders can have “normal” lab results for various reasons including the person’s genetics, the type of test run, time of day, and more.[6,7] A leading eating disorder physician, Dr. Gaudiani, [6] discusses how our bodies are very skilled at trying to keep our physical functioning stable in crisis. Some people’s bodies can maintain this stability longer than others, which could produce “normal” lab results even while long term damage to the body is occurring. Additionally, even within the same person, lab results can change very drastically in a very short amount of time, meaning that your labs can go from “normal” to life-threatening within the same day. “Okay. I get that physical characteristics don’t always show the severity of my eating disorder, but my eating disorder symptoms and behaviors aren’t “as severe” as other people I know, so I don’t deserve help.  FALSE! Even if your eating disorder symptoms “could be worse”, you still deserve help! Waiting to get treatment for your eating disorder often decreases your chances for a full recovery and leads to worsening physical and mental outcomes. I once heard a therapist illustrate this concept well: “If you break a finger, you wouldn’t need to break the other nine fingers to deserve help! You would likely immediately try to fix it”. Your eating disorder is the same! At the end of the day, feeling that you are not “sick enough” to get treatment for your eating disorder is a sign that you are sick enough. People without disordered relationships with food or their bodies do not experience beliefs that being thinner or more malnourished makes you “better” at the illness or more deserving of help. These thoughts are often a part of the illness and an indication that you should reach out for help. Your experiences are valid, and you are deserving of support and recovery regardless of how much you weigh, how long you have had an eating disorder, or your medical lab results. Ready for the support and recovery you deserve? Here are some great resources: National Eating Disorders Association: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/where-do-i-start-0 National Eating Disorders Association Helpline: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/help-support/contact-helpline Free eating disorder support groups: https://anad.org/ Eating Disorder Hope’s Treatment Finder: https://www.eatingdisorderhope.com/ Association for Size Diversity and Health: https://asdah.org/ The Food Psych Podcast by Christy Harrison: https://christyharrison.com/foodpsych References