|

Written by Caroline Christian, M.S., Fourth Year EAT Lab Graduate Student Before reading this blog post, please first take a minute and think about what factors you believe influence how much a person weighs. ****** What was on your list? Was anything on your list related to food or exercise? Were these factors near the top of your list? In American society, as well as in many other parts of the world, there is a common belief that weight is determined almost exclusively by the amount and type of food consumed and amount and type of physical activity. While this is partially true (energy input and output from food and physical activity can impact how much you weigh) there are several, far more important factors that are often left out of the equation, which I will discuss later in this article. If you feel resistant to the idea that weight is more than diet and exercise, you are not alone. Many systems in our society are based on this belief, including virtually every diet and exercise plan that you see advertised today. And it is not an accident that this belief is so pervasive, as many corporations make a ton of money (over 70 billion dollars a year) from this commonly held belief (Marketdata, 2021). Industries that are benefitting include insurance companies, gyms, clothing stores, diet food companies, diet pill corporations, plastic surgeons, weight loss nutritionists, social media influencers, and many more. Do you know who doesn’t benefit from this belief? You. In fact, this belief contributes to many problems in our society. One of which is that this belief fuels stereotypes and discrimination towards people in larger bodies (Nadler & Voyles, 2020). For example, over one third of people in a larger body report being discriminated against due to their size, including being denied jobs and proper healthcare (Sikorski et al., 2016). Second, mental health concerns, including depression, negative body image, and disordered eating, are also linked to misinformation and myths about weight control (Carels et al., 2013; Hayward et al., 2018). Third, this belief leads people in all body types to spend excessive amounts of time and money on products and programs that don’t actually improve health or even influence weight in a lasting way. Beyond the fact that the weight = diet x exercise belief is harmful, this belief is not supported by science. Yes – food and physical activity can have an influence on weight, but these are two of many factors that determine weight (Bacon, 2011). Below, I talk about some of the other factors that are more important to influencing weight than food intake and exercise output.

These are just a few of many examples of how genetic and environmental inequities can influence weight and health; however, these few examples begin to highlight the sheer complexity of how weight can be determined by factors largely out of our control. Briefly, other important factors include

The media, gyms, and diet companies will continue to push the narrative that your weight is a direct consequence of your behaviors related to food and exercise. However, science supports that although a balanced diet and physical activity can improve health, they will not drastically change your weight from its intended set point. There are also numerous systemic and medical factors out of our control that prevent people from engaging in different health behaviors. Thus, it is important to practice compassion for yourself and others around weight. Even now, equipped with this information, you will likely continue to notice automatic judgment towards yourself and others, which is understandable given how engrained these messages are. AND we can do better. I encourage you to try to actively challenge these biases and false beliefs and to show acceptance and kindness to others, regardless of weight, to help dismantle the harm that weight misinformation and stigma can have. If you are interested in reading more about weight and health, I encourage you to explore the following resources.

References: Bacon, L. (2011). Health at Every Size Revised and Updated. ReadHowYouWant.com. Carels, R. A., Burmeister, J., Oehlhof, M. W., Hinman, N., LeRoy, M., Bannon, E., Koball, A., & Ashrafloun, L. (2013). Internalized weight bias: Ratings of the self, normal weight, and obese individuals and psychological maladjustment. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-012-9402-8 Franklin, B., Jones, A., Love, D., Puckett, S., Macklin, J., & White-Means, S. (2012). Exploring Mediators of Food Insecurity and Obesity: A Review of Recent Literature. Journal of Community Health, 37(1), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9420-4 Goodarzi, M. O. (2018). Genetics of obesity: What genetic association studies have taught us about the biology of obesity and its complications. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 6(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30200-0 Hayward, L. E., Vartanian, L. R., & Pinkus, R. T. (2018). Weight Stigma Predicts Poorer Psychological Well-Being Through Internalized Weight Bias and Maladaptive Coping Responses. Obesity, 26(4), 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22126 Hewagalamulage, S. D., Lee, T. K., Clarke, I. J., & Henry, B. A. (2016). Stress, cortisol, and obesity: A role for cortisol responsiveness in identifying individuals prone to obesity. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 56, S112–S120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.domaniend.2016.03.004 Katsu, Y., & Baker, M. E. (2021). Cortisol. In Handbook of Hormones (pp. 947–949). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820649-2.00261-8 Lowe, M. R., Doshi, S. D., Katterman, S. N., & Feig, E. H. (2013). Dieting and restrained eating as prospective predictors of weight gain. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00577 Meyer, J. M., & Stunkard, A. J. (2020). Twin Studies of Human Obesity. In The Genetics of Obesity. CRC Press. Nadler, J. T., & Voyles, E. C. (2020). Stereotypes: The Incidence and Impacts of Bias. ABC-CLIO. Pickett, K. E. (2005). Wider income gaps, wider waistbands? An ecological study of obesity and income inequality. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(8), 670–674. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028795 Rose, K. L., Evans, E. W., Sonneville, K. R., & Richmond, T. (2021). The set point: Weight destiny established before adulthood? Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 33(4), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000001024 Roybal, D. (2005). Is “Yo-Yo” Dieting or Weight Cycling Harmful to One’s Health? Nutrition Noteworthy, 7(1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1zz4r4qk Sikorski, C., Spahlholz, J., Hartlev, M., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2016). Weight-based discrimination: An ubiquitary phenomenon? International Journal of Obesity, 40(2), 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.165 Staiano, A. E., Marker, A. M., Martin, C. K., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2016). Physical activity, mental health, and weight gain in a longitudinal observational cohort of nonobese young adults. Obesity, 24(9), 1969–1975. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21567 Wurtman, J., & Wurtman, R. (2018). The Trajectory from Mood to Obesity. Current Obesity Reports, 7(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0291-6

1 Comment

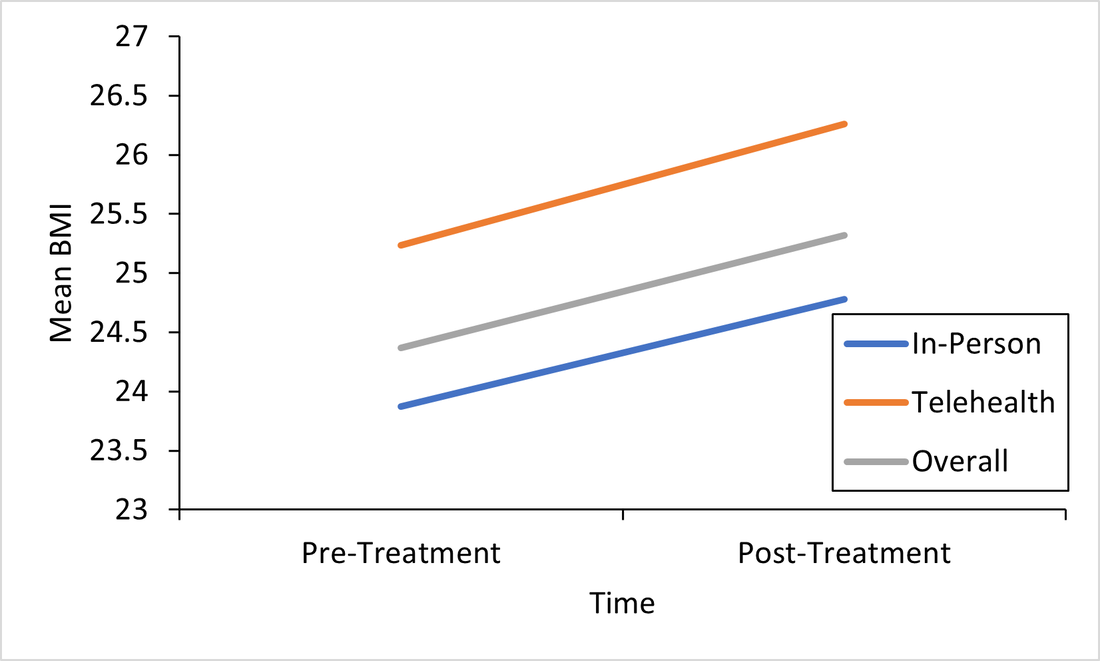

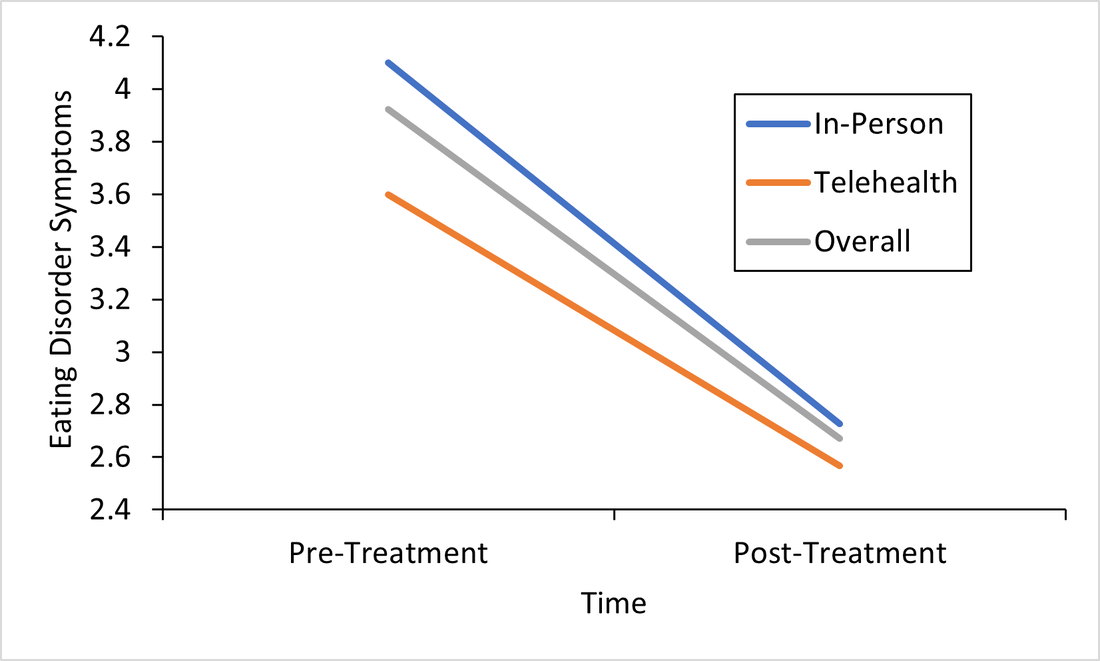

Responding to the Call for Accessibility: Breaking Down Recent Findings on Telehealth Vs. In-Person Eating Disorder Treatment During COVID-19 In Plain Language Written by Samantha Spoor B.S., Former Study Coordinator, Current PhD Student at University of Wyoming and Dr. Cheri A. Levinson, Ph.D. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unique challenges for those with eating disorders , particularly for those seeking support, and for providers who have had to adapt treatment delivery (e.g. virtual, hybrid; telehealth) to attend to barriers to treatment access associated with the pandemic. Most treatment centers responded to the pandemic by moving services either fully or partially online. However, we do not have a lot of science behind this transition. So we sought to change that. Members of our team at the EAT Lab recently published an article in partnership with the Louisville Center for Eating Disorders (LCED1) Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) evaluating outcomes for in-person versus telehealth treatment formats prior to and during the pandemic. In other words, we wanted to know, does telehealth intensive treatment (3 hours a day, 5 days a week) for eating disorders work? We expect that a lot of treatment moving forward will be delivered over telehealth, so it’s a very important question to answer! Read the full article here. To make these important telehealth vs. in-person IOP treatment findings from LCED accessible and understandable, this blog post replaces highly scientific language with a plain language summary of the findings below. We also provide additional comments about why these findings are important and what they show us about the ability of the eating disorder field to increase access to eating disorder treatment through the use of telehealth. Background: COVID-19 led to BOTH 1) more eating disorder symptoms and diagnoses in the general public and 2) worsening eating disorder symptoms for those who had already had an eating disorder (Phillipou et al., 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020). Further, the pandemic also led to increased barriers to accessing treatment, such that in-person treatment delivery became harder to implement while following public health guidelines, and posed a potentially higher risk of contracting COVID-19 for patients with EDs. Lastly, not a whole lot is known about delivering intensive ED treatment (particularly IOP) virtually! Purpose: We were interested in finding out whether moving the traditionally in-person IOP program to virtual in response to the COVID-19 pandemic would affect treatment outcomes. In other words, we were interested in the following questions: 1) Will eating disorder, depression, and anxiety symptoms decrease from admission to the IOP program to discharge, and 2) Will they decrease similarly regardless of if the treatment is in-person or fully online (telehealth)? Method: Participants (Who): Overall we had 93 participants with eating disorders go through the IOP program. About 60 patients received in-person (traditional) IOP treatment prior to COVID-19 and about 33 patients received virtual IOP treatment during COVID-19. These patients completed outcome measures of eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, and depression before and after treatment and agreed that we could use their data for research purposes. This sample of patients included individuals with Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge Eating Disorder (BED), Otherwise Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), and Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). In other words, patients with a wide variety of ED diagnoses participated in the research reported in this paper! Patients also reported a variety of other psychiatric diagnoses (in addition to ED diagnoses). Check out the article for figures and tables showing the breakdown of diagnoses! Procedure (How): Treatment for those enrolled in the IOP program prior to the COVID-19 pandemic participated in treatment on average for 10 weeks. All treatment was in-person. For those who enrolled during COVID-19, the same exact treatment format was implemented, but the delivery was completely online and virtual. Measures (What): For this study, we included measures of body mass index (BMI), and eating disorder, depression, and perfectionism symptoms as outcomes. You can read more about the specific scales we used in the full paper, but these were chosen because they are all important features of eating disorder treatment outcomes. For example, perfectionism has been shown to be intimately involved in eating disorders (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007). Analytic Approach: We also ran statistics to determine if there were any major differences in our outcome measures at the start of treatment (reminder: BMI & eating disorder symptoms, depression, or perfectionism symptoms) between those who started treatment prior to COVID-19, or after COVID-19 (there were a few - see below). Repeated Measures ANOVAS (Click to learn more) were used to assess if there were significant differences in outcomes for those who received virtual (during COVID-19) or in-person (prior to COVID-19) IOP treatment. This means- we tested are there differences in how well the IOP treatment works that depends on format (in-person or telehealth)? Results: The only significant differences between the virtual vs. in-person groups at the start of treatment were that the in-person group was more concerned than the virtual group was with two aspects of perfectionism that we measured: parental expectations and criticism. This result does not really mean much, but we always test for differences between groups when doing this type of research. Here are the important findings: BMI (weight): BMI increased overall and increased in both groups. See the Figure! The gray line are all the participants; the orange line are participants who did treatment via telehealth, and the blue is in-person. All the lines increase, which is what we want (for BMI specifically)! And, there were no differences between groups.  This is important because weight gain is a good sign that ED treatment is going well. Eating Disorder Symptoms: Eating disorder symptoms went down overall and went down in both the in-person and telehealth groups. Again, there were no differences between groups. This means that both treatment formats make eating disorder symptoms better! See Figure below, remember, the gray line are all the participants; the orange line are participants who did treatment via telehealth, and the blue is in-person. We won’t bore you with the additional figures, but you can find them in the full paper! We did find the same pattern for the rest of our outcomes: depression and perfectionism decreased similarly across treatment, regardless of whether patients received in-person or telehealth treatment. This is what we want to see!

Conclusions: Eating disorder symptoms decreased. BMI increased. Depression and perfectionism decreased. This is what we want! And importantly , all outcomes were comparable across both groups. This means that telehealth team-based eating disorder intensive outpatient programming (IOP)is not only possible, but also may be equally as effective as traditional in-person team-based IOP treatment for eating disorders. At least, that is what we found in our sample in Kentucky. We hope to see more of this research throughout the U.S. in the future! There are a few limitations to consider regarding this research. Firstly, most of our sample was composed of white women, which, while representative of those who are most likely to access treatment, seriously limits the generalizability of our findings to truly representative and diverse populations of those with EDs. In other words, people of all races and genders can (and do) have eating disorders (Burke et al., 2020; Feldman & Meyer, 2007; Smolak & Striegel-Moore, 2001), and we have no way of knowing based on this study if our findings would apply to them, too. This is especially concerning given that those with marginalized identities, such as Black, Indiginous, and People of Color (BIPOC), and queer individuals, are frequently underserved in the eating disorder field. A few other important limitations include that we had a relatively small sample size (meaning having more people in the study would have increased our confidence in the findings), and that this wasn’t a randomized control trial (so we weren’t able to randomly select who got which type of treatment delivery, since we obviously did not predict the onset of the pandemic or offer any in-person treatment during COVID-19). Limitations considered, there are still HUGE implications for increasing treatment access to those who otherwise might not be able to receive in-person eating disorder treatment. If we can do eating disorder IOP as well virtually as in-person, then there is no reason that those who a) cannot afford transportation to treatment, b) live in rural areas, or c) simply live too far away from specialized treatment to commute, should be denied the opportunity. In this way, COVID-19 may precipitate long-overdue efforts to increase ED treatment access for underserved communities. Get Involved! Treatment Access Resource & Study: If you or someone you know has struggled to access high-quality eating disorder treatment for any reason at all, please consider checking out one of our EAT Lab partners, Project HEAL, for treatment access resources. Additionally, we are currently hosting a short, confidential online study (5-10 minutes long) in partnership with Project HEAL, to help the field understand the overlap and impact of various treatment access barriers for those with eating disorders. Please consider participating if you meet eligibility criteria outlined at the beginning of the survey and want to help. If you have questions about the plain language study summary (or the original article, linked above), please reach out to us via the comment board below on this page, and we would be delighted to correspond with you (or clarify anything better). And, if you’d like to see more content on the blog like this, let us know! Thank you! 1LCED is the only program in the state of Kentucky offering specialized IOP treatment for eating disorders. The center uses a multidisciplinary team-based approach to intensive eating disorder treatment, wherein psychologists, therapists, dieticians, and prescribers come together to treat each patient in an evidence-based and personalized manner. Citation: Levinson, C.A., Spoor, S.P., Keshishian, A.C., & Pruitt, A. (in press). Pilot outcomes from a multidisciplinary telehealth vs in-person intensive outpatient program for eating disorders during vs before the Covid-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders. References Bardone-Cone, A. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Frost, R. O., Bulik, C. M., Mitchell, J. E., Uppala, S., & Simonich, H. (2007). Perfectionism and eating disorders: Current status and future directions. Clinical psychology review, 27(3), 384-405. Burke, N. L., Schaefer, L. M., Hazzard, V. M., & Rodgers, R. F. (2020). Where identities converge: The importance of intersectionality in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(10), 1605-1609. Feldman, M. B., & Meyer, I. H. (2007). Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. International journal of eating disorders, 40(3), 218-226. Phillipou, A., Meyer, D., Neill, E., Tan, E. J., Toh, W. L., Van Rheenen, T. E., & Rossell, S. L. (2020). Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1158– 1165. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23317 Schlegl, A., Maier, J., Meule, A., & Voderholzer, U. (2020). Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1791– 1800. https://doi-org.echo.louisville.edu/10.1002/eat.23374 Smolak, L., & Striegel-Moore, R. H. (2001). Challenging the myth of the golden girl: Ethnicity and eating disorders. In R. H. Striegel-Moore & L. Smolak (Eds.), Eating disorders: Innovative directions in research and practice (pp. 111–132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10403-006 |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed