|

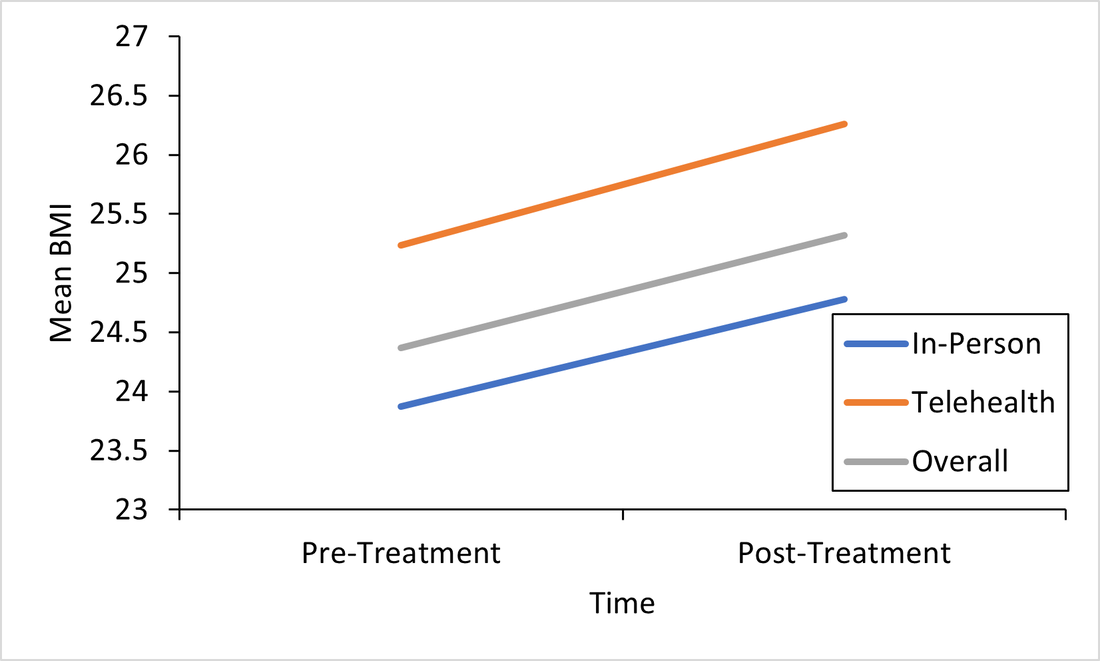

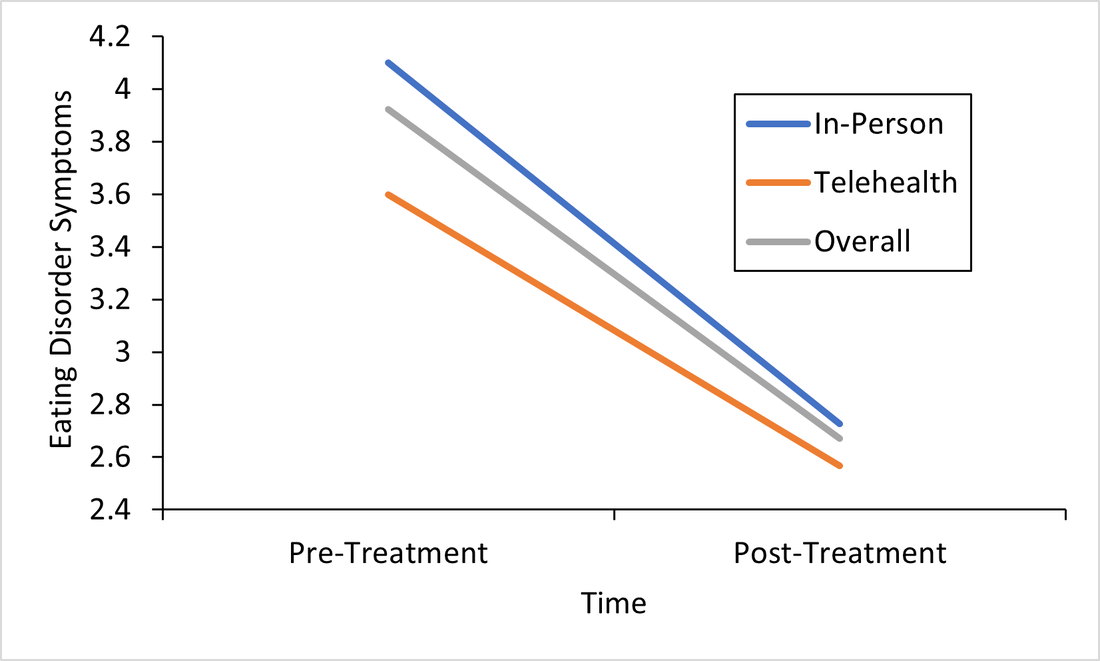

Responding to the Call for Accessibility: Breaking Down Recent Findings on Telehealth Vs. In-Person Eating Disorder Treatment During COVID-19 In Plain Language Written by Samantha Spoor B.S., Former Study Coordinator, Current PhD Student at University of Wyoming and Dr. Cheri A. Levinson, Ph.D. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unique challenges for those with eating disorders , particularly for those seeking support, and for providers who have had to adapt treatment delivery (e.g. virtual, hybrid; telehealth) to attend to barriers to treatment access associated with the pandemic. Most treatment centers responded to the pandemic by moving services either fully or partially online. However, we do not have a lot of science behind this transition. So we sought to change that. Members of our team at the EAT Lab recently published an article in partnership with the Louisville Center for Eating Disorders (LCED1) Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) evaluating outcomes for in-person versus telehealth treatment formats prior to and during the pandemic. In other words, we wanted to know, does telehealth intensive treatment (3 hours a day, 5 days a week) for eating disorders work? We expect that a lot of treatment moving forward will be delivered over telehealth, so it’s a very important question to answer! Read the full article here. To make these important telehealth vs. in-person IOP treatment findings from LCED accessible and understandable, this blog post replaces highly scientific language with a plain language summary of the findings below. We also provide additional comments about why these findings are important and what they show us about the ability of the eating disorder field to increase access to eating disorder treatment through the use of telehealth. Background: COVID-19 led to BOTH 1) more eating disorder symptoms and diagnoses in the general public and 2) worsening eating disorder symptoms for those who had already had an eating disorder (Phillipou et al., 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020). Further, the pandemic also led to increased barriers to accessing treatment, such that in-person treatment delivery became harder to implement while following public health guidelines, and posed a potentially higher risk of contracting COVID-19 for patients with EDs. Lastly, not a whole lot is known about delivering intensive ED treatment (particularly IOP) virtually! Purpose: We were interested in finding out whether moving the traditionally in-person IOP program to virtual in response to the COVID-19 pandemic would affect treatment outcomes. In other words, we were interested in the following questions: 1) Will eating disorder, depression, and anxiety symptoms decrease from admission to the IOP program to discharge, and 2) Will they decrease similarly regardless of if the treatment is in-person or fully online (telehealth)? Method: Participants (Who): Overall we had 93 participants with eating disorders go through the IOP program. About 60 patients received in-person (traditional) IOP treatment prior to COVID-19 and about 33 patients received virtual IOP treatment during COVID-19. These patients completed outcome measures of eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, and depression before and after treatment and agreed that we could use their data for research purposes. This sample of patients included individuals with Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge Eating Disorder (BED), Otherwise Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), and Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). In other words, patients with a wide variety of ED diagnoses participated in the research reported in this paper! Patients also reported a variety of other psychiatric diagnoses (in addition to ED diagnoses). Check out the article for figures and tables showing the breakdown of diagnoses! Procedure (How): Treatment for those enrolled in the IOP program prior to the COVID-19 pandemic participated in treatment on average for 10 weeks. All treatment was in-person. For those who enrolled during COVID-19, the same exact treatment format was implemented, but the delivery was completely online and virtual. Measures (What): For this study, we included measures of body mass index (BMI), and eating disorder, depression, and perfectionism symptoms as outcomes. You can read more about the specific scales we used in the full paper, but these were chosen because they are all important features of eating disorder treatment outcomes. For example, perfectionism has been shown to be intimately involved in eating disorders (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007). Analytic Approach: We also ran statistics to determine if there were any major differences in our outcome measures at the start of treatment (reminder: BMI & eating disorder symptoms, depression, or perfectionism symptoms) between those who started treatment prior to COVID-19, or after COVID-19 (there were a few - see below). Repeated Measures ANOVAS (Click to learn more) were used to assess if there were significant differences in outcomes for those who received virtual (during COVID-19) or in-person (prior to COVID-19) IOP treatment. This means- we tested are there differences in how well the IOP treatment works that depends on format (in-person or telehealth)? Results: The only significant differences between the virtual vs. in-person groups at the start of treatment were that the in-person group was more concerned than the virtual group was with two aspects of perfectionism that we measured: parental expectations and criticism. This result does not really mean much, but we always test for differences between groups when doing this type of research. Here are the important findings: BMI (weight): BMI increased overall and increased in both groups. See the Figure! The gray line are all the participants; the orange line are participants who did treatment via telehealth, and the blue is in-person. All the lines increase, which is what we want (for BMI specifically)! And, there were no differences between groups.  This is important because weight gain is a good sign that ED treatment is going well. Eating Disorder Symptoms: Eating disorder symptoms went down overall and went down in both the in-person and telehealth groups. Again, there were no differences between groups. This means that both treatment formats make eating disorder symptoms better! See Figure below, remember, the gray line are all the participants; the orange line are participants who did treatment via telehealth, and the blue is in-person. We won’t bore you with the additional figures, but you can find them in the full paper! We did find the same pattern for the rest of our outcomes: depression and perfectionism decreased similarly across treatment, regardless of whether patients received in-person or telehealth treatment. This is what we want to see!

Conclusions: Eating disorder symptoms decreased. BMI increased. Depression and perfectionism decreased. This is what we want! And importantly , all outcomes were comparable across both groups. This means that telehealth team-based eating disorder intensive outpatient programming (IOP)is not only possible, but also may be equally as effective as traditional in-person team-based IOP treatment for eating disorders. At least, that is what we found in our sample in Kentucky. We hope to see more of this research throughout the U.S. in the future! There are a few limitations to consider regarding this research. Firstly, most of our sample was composed of white women, which, while representative of those who are most likely to access treatment, seriously limits the generalizability of our findings to truly representative and diverse populations of those with EDs. In other words, people of all races and genders can (and do) have eating disorders (Burke et al., 2020; Feldman & Meyer, 2007; Smolak & Striegel-Moore, 2001), and we have no way of knowing based on this study if our findings would apply to them, too. This is especially concerning given that those with marginalized identities, such as Black, Indiginous, and People of Color (BIPOC), and queer individuals, are frequently underserved in the eating disorder field. A few other important limitations include that we had a relatively small sample size (meaning having more people in the study would have increased our confidence in the findings), and that this wasn’t a randomized control trial (so we weren’t able to randomly select who got which type of treatment delivery, since we obviously did not predict the onset of the pandemic or offer any in-person treatment during COVID-19). Limitations considered, there are still HUGE implications for increasing treatment access to those who otherwise might not be able to receive in-person eating disorder treatment. If we can do eating disorder IOP as well virtually as in-person, then there is no reason that those who a) cannot afford transportation to treatment, b) live in rural areas, or c) simply live too far away from specialized treatment to commute, should be denied the opportunity. In this way, COVID-19 may precipitate long-overdue efforts to increase ED treatment access for underserved communities. Get Involved! Treatment Access Resource & Study: If you or someone you know has struggled to access high-quality eating disorder treatment for any reason at all, please consider checking out one of our EAT Lab partners, Project HEAL, for treatment access resources. Additionally, we are currently hosting a short, confidential online study (5-10 minutes long) in partnership with Project HEAL, to help the field understand the overlap and impact of various treatment access barriers for those with eating disorders. Please consider participating if you meet eligibility criteria outlined at the beginning of the survey and want to help. If you have questions about the plain language study summary (or the original article, linked above), please reach out to us via the comment board below on this page, and we would be delighted to correspond with you (or clarify anything better). And, if you’d like to see more content on the blog like this, let us know! Thank you! 1LCED is the only program in the state of Kentucky offering specialized IOP treatment for eating disorders. The center uses a multidisciplinary team-based approach to intensive eating disorder treatment, wherein psychologists, therapists, dieticians, and prescribers come together to treat each patient in an evidence-based and personalized manner. Citation: Levinson, C.A., Spoor, S.P., Keshishian, A.C., & Pruitt, A. (in press). Pilot outcomes from a multidisciplinary telehealth vs in-person intensive outpatient program for eating disorders during vs before the Covid-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders. References Bardone-Cone, A. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Frost, R. O., Bulik, C. M., Mitchell, J. E., Uppala, S., & Simonich, H. (2007). Perfectionism and eating disorders: Current status and future directions. Clinical psychology review, 27(3), 384-405. Burke, N. L., Schaefer, L. M., Hazzard, V. M., & Rodgers, R. F. (2020). Where identities converge: The importance of intersectionality in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(10), 1605-1609. Feldman, M. B., & Meyer, I. H. (2007). Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. International journal of eating disorders, 40(3), 218-226. Phillipou, A., Meyer, D., Neill, E., Tan, E. J., Toh, W. L., Van Rheenen, T. E., & Rossell, S. L. (2020). Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1158– 1165. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23317 Schlegl, A., Maier, J., Meule, A., & Voderholzer, U. (2020). Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1791– 1800. https://doi-org.echo.louisville.edu/10.1002/eat.23374 Smolak, L., & Striegel-Moore, R. H. (2001). Challenging the myth of the golden girl: Ethnicity and eating disorders. In R. H. Striegel-Moore & L. Smolak (Eds.), Eating disorders: Innovative directions in research and practice (pp. 111–132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10403-006

6 Comments

10/16/2022 10:02:03 pm

I appreciate your saying that team-based intense outpatient programming (IOP) for eating disorders is not only feasible but could be just as successful as conventional in-person IOP. My relative experienced eating disorders. I'll get her an intensive outpatient therapy program.

Reply

9/25/2023 12:10:29 am

Thanks for sharing. I really appreciate it that you shared with us such informative post, great tips and very easy to understand.

Reply

9/25/2023 12:43:29 am

Very nice article, exactly what I needed. Very useful post I really appreciate thanks for sharing such a nice post. Thanks

Reply

11/29/2023 02:35:59 am

This was a great and interesting article to read. I have really enjoyed all of this very cool and fun information. Thanks

Reply

5/19/2024 04:53:01 am

The findings from this study on telehealth versus in-person intensive outpatient programs (IOP) for eating disorder treatment are incredibly promising. It's encouraging to see that both formats resulted in significant improvements in key measures like BMI, eating disorder symptoms, depression, and anxiety. This suggests that telehealth can be just as effective as traditional in-person treatment, which is a game-changer for accessibility. The ability to receive high-quality care remotely can help bridge the gap for those who face barriers to in-person treatment, such as geographic limitations or health concerns. It's a vital step forward in making effective treatment more inclusive and widely available, especially in times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. Kudos to the research team for addressing this important issue and providing evidence that supports the efficacy of telehealth in eating disorder treatment.

Reply

5/19/2024 05:24:01 am

The study's findings underscore the importance of adapting eating disorder treatment to virtual formats, especially during times like the COVID-19 pandemic. It's encouraging to see that both in-person and telehealth formats were equally effective in increasing BMI and addressing symptoms, offering hope for increased accessibility to crucial support for those in need.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed