|

Check out the Courier Journal article that Dr. Levinson helped with:

http://www.courier-journal.com/story/life/wellness/2016/10/27/your-brain-fear-why-some-people-seek-scary/92379802/

0 Comments

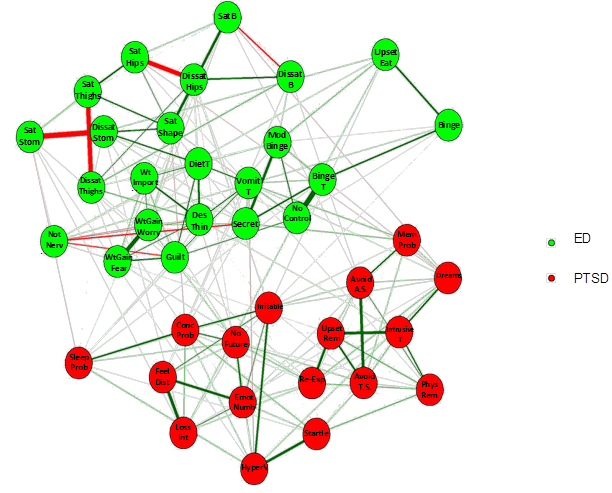

Network Models of Psychopathology Part II by Benjamin Calebs, B.A. Clinical Implications of Network Analysis Network analysis can also help identify which symptoms might be most important to maintaining a mental disorder. If we can identify the most important symptoms of a disorder, then perhaps clinical interventions targeted at these symptoms could cause reductions in the severity of other symptoms in the network (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; McNally, 2016). For example, if a client has symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder such as irritability, insomnia, and worry, network models suggest that it would be beneficial to target the core symptoms that are causally related to many others within the mental disorder. If clinicians were to target the symptom of excessive worry then this could reduce both the insomnia and the irritability arising from the insomnia. By targeting core symptoms in this manner, therapeutic interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy could indirectly impact many other symptoms of a mental disorder. Comorbidity Network analysis also affords researchers a deeper understanding of comorbidity (two or more disorders occurring at the same time) between different mental disorders (Cramer, Waldorp, van der Maas, & Borsboom, 2010). Many mental disorders are highly comorbid with other mental disorders. When mental disorders are conceptualized as networks of symptoms, researchers can look at the interaction between specific symptoms across disorders that may be contributing to the comorbidity. For example, researchers could look at a comorbidity network containing symptoms of both post-traumatic stress disorder and eating disorders to see how the disorders interact (see figure below from some exciting new work in our lab!). Researchers could then look for core symptoms in a comorbidity network in the same way that one looks for such symptoms in a single disorder. Researchers can also look for symptoms that bridge the mental disorders to see how symptoms of one disorder might relate to the development of symptoms in other disorders (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). If targeted clinical interventions are directed at the core symptoms or bridge symptoms in a comorbidity network then this could reduce symptoms across the different mental disorders.

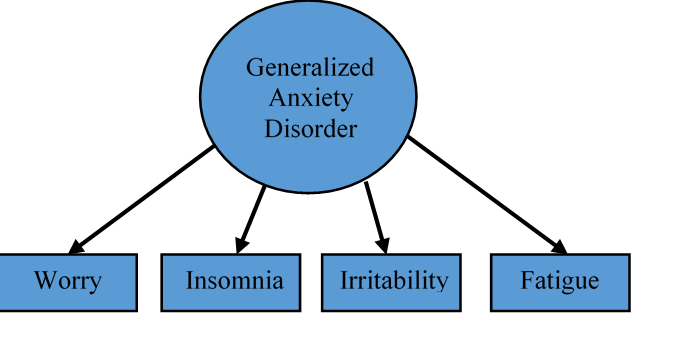

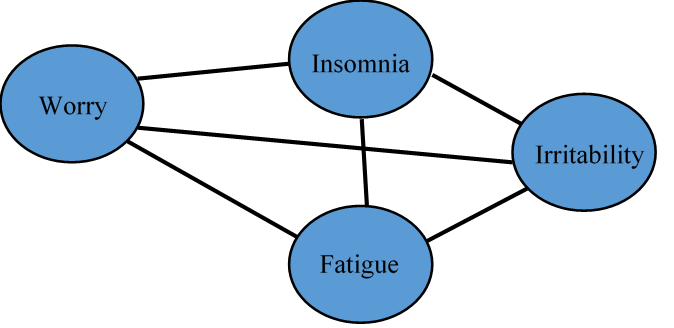

Network models of psychopathology also have the benefit of allowing researchers to look at causal relationships between the different symptoms (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; McNally, 2016). However, to actually determine causality one would need to gather longitudinal or experimental data. This is one of the exciting directions in which research on network models of psychopathology is headed. Researchers are beginning to develop ways of comparing networks across time to see how changes in the network structure of a mental disorder relate to changes in symptom severity (Beard et al., 2016; van Borkulo et al., 2015). As can be seen, network models of psychopathology have many benefits and open up exciting possibilities for both research and clinical practice. Network Models of Psychopathology Part I Benjamin Calebs, B.A. The precise nature of mental disorders has often been debated within the field of psychology. In particular, psychologists have debated about whether mental disorders are socially-constructed or whether they are biologically-based like other medical diseases. One exciting new way to address this issue is the network approach to psychopathology (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; McNally, 2016). This approach involves a reconceptualization of psychopathology that builds on insights from various perspectives on the nature of mental disorders. However, before exploring where the field of psychology may be headed, it would be useful to start with a look at where psychology has been. This will be helpful for understanding and appreciating network models of psychopathology. Categories versus Dimensions? As was mentioned, psychologists have different theories about the nature of mental disorders. There has also been much debate about whether psychopathology should be measured using a categorical framework or a dimensional framework. A categorical conceptualization of psychopathology uses a cut-off score to define who has a mental disorder and who does not. In this framework, an individual either has or does not have a mental disorder. The problem with cut-off scores is that a cut-off can seem arbitrary and may not necessarily relate to the impairment that an individual experiences as a consequence of their symptoms of psychological distress. A dimensional conceptualization looks at mental disorders as sets of symptoms that many individuals experience to some degree but that some individuals experience more than others. For example, many people might get sad from time to time, but someone with depression would have this experience more days than not over an extended period of time. The dimensional approach highlights this inherent variability across individuals in symptoms that are associated with mental disorders. Latent Variable Theory? Interestingly both of these frameworks (i.e., the categorical framework and the dimensional framework) operate from a shared underlying theory that is often taken for granted. This theory is known as latent variable theory (Borsboom et al., 2016; Eaton, 2015; McNally, 2016). Latent variable theory is based on the idea that many mental disorders are latent constructs that are unobservable. This implies that mental disorders cannot be directly measured. However, researchers and clinicians can gather information about the symptoms associated with mental disorders, such as thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. For example, latent variable theory suggests that generalized anxiety disorder is not directly observable, but the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder can be observed and measured. Clinicians and researchers use measures of observable anxiety symptoms like worry, insomnia, fatigue, and irritability to evaluate an individual’s level of anxiety. The number and severity of anxiety symptoms are used to identify clinically relevant generalized anxiety (Borsboom et al., 2016; Eaton, 2015). Latent variable theories of mental disorders borrow the model of disease from the field of medicine (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Borsboom et al., 2016; Eaton, 2015). Following latent variable theory, a mental disorder is considered a disease that causes symptoms (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder causes insomnia and fatigue) in the same way that a physical disease causes physical symptoms (e.g., asthma causes coughing). However, there are some shortcomings associated with this understanding of psychopathology. It is unclear if there is a single underlying cause behind many mental disorders in the same way as exists for physical diseases. For example, it is known that coronary heart disease is caused by a build-up of plaque deposits in the coronary arteries and that this can, in turn, cause symptoms such shortness of breath and chest pain. Yet it is unclear if mental disorders behave in this same way. Also, the symptoms of mental disorders are considered independent of one another in latent variable theory. This means that it is assumed that the symptoms are unrelated to each other. Instead, symptoms are theorized to be associated because of their relationship to the underlying, unobservable mental disorder. Networks of Symptoms? Researchers in the field of psychometrics, which is the study of how psychological constructs are measured, have begun to apply a novel theoretical framework known as network theory to help understand psychopathology (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; McNally, 2016). Network theory is an interdisciplinary field that studies anything that can be conceptualized as a collection of parts that are connected in some way. Network theory has been applied to a variety of domains. Network researchers have looked at everything from neural networks to food webs to economies. Network theory and analysis have often been applied to social networks with individuals acting as nodes in a network and the relationships between them serving as links. Network analysis can be used to study the structure of networks, as well as the dynamic interaction between the different nodes (Newman, 2003). In the study of psychopathology, the symptoms are considered nodes and the correlations between them are considered the links. Mental disorders can then be conceptualized as a network of symptom nodes. For example, an eating disorder could be conceptualized as a network consisting of symptoms such as the fear of gaining weight, a strong desire to be thin, and dissatisfaction with one’s body shape (Forbush, Siew, & Vitevitch, 2016). Clinicians and researchers also acknowledge that mental disorder symptoms have the potential to interact, with symptoms of a disorder acting as the cause of other symptoms within that same disorder. For example, someone with generalized anxiety disorder could experience severe worrying. These worries could cause the person to lose sleep. This insomnia could, in turn, lead to irritability and fatigue as the individual is unable to get adequate rest (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Borsboom et al., 2016; Eaton, 2015). The different symptoms of a mental disorder are related, but some might be more related than others. Network analysis can help researchers better understand how the symptoms of which a mental disorder is composed are related. Why do we care about these different models of psychopathology? Stay tuned for Part II where we discuss clinical implications of network analysis and show some of the work we’ve been doing in the EAT lab.

Eating Disorder Outcomes: Does Intensive Eating Disorder Treatment Help?

By Laura Fewell, B.A. Eating disorders (EDs) are serious illnesses that can come in lots of different forms. Restricting food, binge eating, purging, and over-exercising can lead to severe health consequences, such as imbalanced electrolytes and metabolic disturbances, slow or irregular heartbeats, and severe low or high weight. In fact, anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. Often times, EDs are also accompanied by severe anxiety and depression. Yet many people with EDs do not understand how serious the effects of EDs are, and they are not sure where to go or what to do for help. So what are their options? Where do people go for help? And does it work? Many people with eating disorders can benefit from seeing a team of outpatient specialists, such as therapists, dietitians, and psychiatrists. Yet others need more intensive treatment with structured care and medical management, such as inpatient (24 hour treatment in a hospital), residential (24 hour treatment in a home-like facility), and partial hospitalization (day treatment programs, typically 6 to 10 hours a day). But the literature shows mixed outcomes from intensive treatment centers, and much of the available research has been conducted on small samples. As the research coordinator at an eating disorder clinic, I wanted to look at the outcomes in our population and share those with others. Since 2012, I have been collecting data from our patients (in either residential or partial hospitalization programming) to get a better idea of what people with EDs experience, how clients progress throughout intensive treatment, and if clients are doing better after treatment. I also wanted to investigate factors that may contribute to relapse or success after treatment, such as anxiety or how long someone has had an ED. The measures I’ve used look at ED thoughts and behaviors, social impairment, worry, depression, quality of life, and change in weight. More recently, I’ve added in measures looking at obsessive compulsive traits and compulsive exercise (stay tuned for those results!). We currently have data on over 500 patients, and together with Dr. Cheri Levinson, we analyzed the data to test my two primary questions. First, do patients with eating disorders improve? And then, what thoughts and behaviors are related to improvement? We found that patients have improved ED thoughts and behaviors, social impairment, worry, depression, quality of life, and change in weight after receiving intensive ED treatment. What’s more, patients continue to have improved symptoms as long as a year following treatment discharge. This is huge! This tells us that people who have serious EDs and go through intensive treatment can not only get their health back on track, but also see improvements in their mood and quality of life. Next, we looked at what thoughts and behaviors are related to this improvement. We found that worry and depression were contributing to more eating disorder issues later on. We also found that when clients weren’t functioning at a high social level (for example, getting along with others or engaging in life activities), they were experiencing more eating disorder issues later on. So when worry, depression, and social functioning are focused on as part of ED treatment, clients are more likely to do better after treatment. To learn more about our results, stop by the ABCT Obesity and Eating Disorders Special Interest Group Poster Session on Friday, October 27th at 6:30pm! https://www.eventscribe.com/2016/ABCT/aaSearchByDay.asp?h=Full%20Schedule&BCFO=P|MCS|WK|AM|CIT|SS|CGR|CR|IP|LA|MP|MWK|PD|SYM|INS|SIG|RPD|PA While there is still much to be learned in the world of EDs, we are encouraged to find our ED treatment is effective and can lead to improved lives for those who suffer from EDs. We will continue to collect information that informs ED treatment centers practices, but in the meantime, those who struggle with EDs can be comforted to know there is help out there. If you or someone you know might struggle with an eating disorder, please reach out and talk to someone. Help can be found through the National Eating Disorders Association’s confidential hotline 1-800-931-2237. You can also reach out to Dr. Cheri Levinson at [email protected] or to McCallum Place Eating Disorder Treatment Centers at 800-828-8158. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed