|

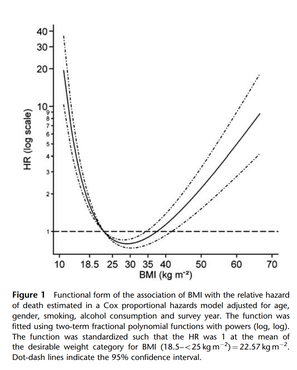

Written by Gabby Davis, B.A., Lab Manager and Christina Ralph-Nearman, PhD, Postdoctoral Research Associate Body Mass Index, or BMI, has long been utilized by medical professionals and the general public alike to categorize the health of individuals. First seeing widespread use starting in the 1970s, BMI was created by a team of healthcare professionals to ‘accurately’ assess the health of their clients based on their height and weight. Or is that really the case? Spoiler alert: it’s not the case at all. BMI is invalid. In actuality, the weight-to-height formula used in calculating BMI was first introduced in 1832 by Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer and mathematician (notably, with no medical background). Quetelet’s formula sought to categorize bodies based on body fat percentage with no initial connection to assessing the health of the individuals being categorized. However, in 1972, Dr. Ancel Keys first coined the term “body mass index” in a manuscript published in an academic journal. Following the publication of that article, BMI was widely used to categorize sedentary populations’ weight health [1], and then morphed into a primary health screening tool for medical professionals and the National Institutes of Health. BMI was (and still is) primarily used in assessing personalized health risks almost exclusively related to being fat. We also want to note that BMI was developed, tested, and ‘validated’ only on a white male sample. BMI was not developed, tested, or ‘validated’ for individual health, and another problem with BMI is that it does not account for the many diverse types of bodies in women and diverse ethnicities. It’s worth taking a read more about how BMI is actually rooted strongly in racism. A great read to check out is: Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia Dr. Sabrina Strings. You may ask yourself, “Okay, but why is that a bad thing? Isn’t it good to know the health risks you face at higher BMIs?” I asked myself the same question, too. The truth is that BMI’s categories were arbitrarily determined without any scientific evidence backing the claims being made by proponents of the measure. Since the use of BMI as a health screening tool first began, several studies have come out demonstrated correlations – not causal effects – between high BMI and chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, and some cancers. Surely this demonstrates that BMI has some scientific validity, right? Unfortunately, there is a significant blind spot that researchers have not investigated nearly as much. Several studies have demonstrated that the rates of chronic disease in those with “high” BMIs (>25) were similar to, or even lower than, those with “healthy” (18.5-25) or “low” (<18.5) BMIs, and that public perception of the “dangers” of being obese are dramatically skewed or at times entirely inaccurate [2,3]. In fact, data shows that a BMI between 25-35 is actually correlated with the lowest risk of early death [4,5]. Take a look at the chart down below, which visually demonstrates the risk associated with different BMIs – it might not be what you expect [5]. This research seems to go mostly ignored or discounted. Why is that? The reality is that there are far more factors than the ratio of one’s weight-to-height, such as stress, genetics, and mental health, that influence the onset and development of chronic diseases and other health-related consequences. Despite this, portions of Western society remain hyper-fixated on weight loss as a “cure-all” for chronic diseases. This leads to fat individuals experiencing potential medical trauma after being told countless times that their weight is the primary reason that they are not well. With only a 5% success rate, weight-loss diets are not sustainable or effective, and many individuals end up feeling defeated and developing a troubled relationship with food and their bodies as a result of repeated attempts at weight loss [6,7,8]. Western society is deeply rooted in what is known as diet culture, or a system which prioritizes a person’s weight, shape, and size over their health and well-being. The continued use of BMI, both professionally and colloquially, as a measure of the health of an individual is both a result of diet culture beliefs being spread and it also reinforces these beliefs, such as an individual feeling they need to be a certain BMI in order to be considered “healthy.” However, for many individuals, it is impossible to attain their “ideal” BMI through no fault of their own. As mentioned before, there are several other factors that play a role in an individual’s health and well-being, including genetics. If an individual is fixated on attaining a particular BMI but are unable to do so by traditional means (dietary and exercise changes), this may pave the way for disordered eating behaviors to emerge, which then have the potential to develop into an eating disorder. So how do you end the cycle of diet culture in your own life? THE FIRST STEP is to identify and challenge the ways you may think about weight and size that may be rooted in diet culture. Changing the way that you think about these topics is the first step to take in helping us dismantle diet culture. THE NEXT STEP is to practice engaging in RESPECT – an acronym with actions to take to help combat the negative influence of diet culture. Health At Every Size (HAES) is a great resource to check out. The HAES model seeks to decrease weight stigma and dismantle diet culture by promoting and supporting the idea with empirical research that all individuals can be healthy, regardless of their BMI. Instead of focusing on controlling an individual’s weight, HAES instead supports people wanting to make changes to health-related behaviors for the sake of their overall well-being, and not making weight loss the primary goal. See the HAES website here to learn more: https://asdah.org/health-at-every-size-haes-approach/

Interested in learning more? Women 18 or older may elect to check out either the Diet Culture Intervention or Wellness Resource, two free self-guided therapeutic interventions targeted at learning more about health, wellness, and combatting diet culture. You may only participate in one of these studies. You also will have a chance to win one of two gift baskets valued at $150 each, including an Amazon gift card and anti-diet culture books and resources! Submit an interest form here: https://www.louisvilleeatlab.com/online-single-session-resources.html or reach out to [email protected] with inquiries. References

2 Comments

|

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed