|

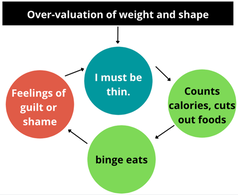

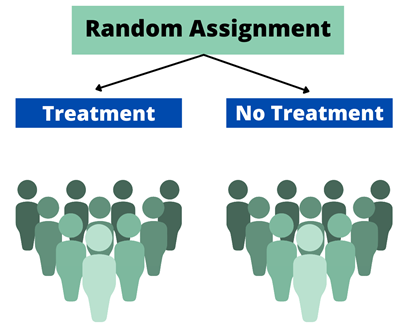

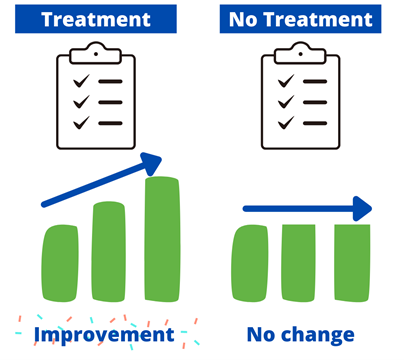

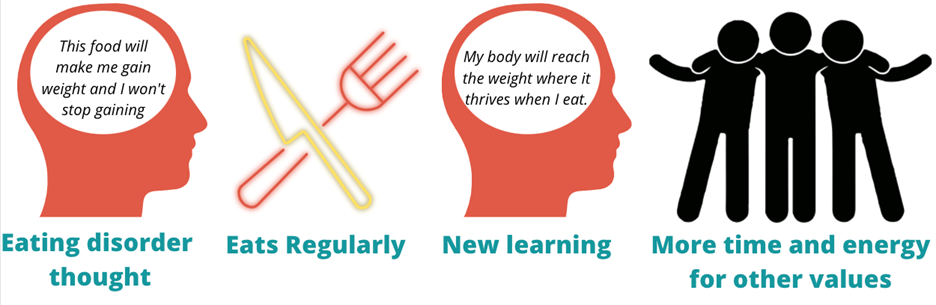

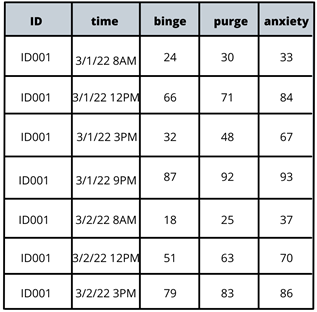

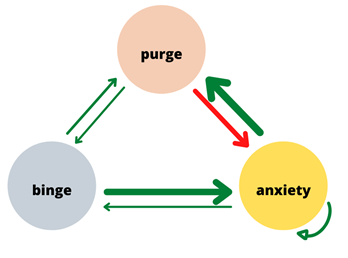

Written by Claire Cusack, M.A., First Year Graduate Student You may be wondering how eating disorder treatments have been developed, how that is currently shifting, and what this might mean for you in your recovery. This post centers these questions. I briefly describe what has been done in the past research, some ways our lab is changing the game, and what that means for you. How we develop treatments The process for developing evidence-based treatments for psychiatric disorders is undeniably complex. At its most basic (and perhaps ideal) form, the process involves developing a theory (e.g., a testable hypothesis of what causes or maintains disorders given a certain set of assumptions) of what causes internal suffering and/or challenges in work, school, or social life, coupled with strategies to address this cause. Generally, a group of people with said suffering complete surveys inquiring on a range of symptoms. Then, a random half of participants receive the treatment, and the other half does not (i.e., a randomized clinical trial; RCT). The group of participants who do not receive the treatment are referred to as the control group, and they may be on a “waitlist,” or receive an existing treatment. After completing treatment, participants in both groups report their current level of symptoms again. If the group that received the treatment demonstrated improved therapeutic outcomes (e.g., less symptoms, less impairment, greater quality of life) relative to the control group, the treatment has initial empirical support.  If research accumulates with similar findings, this treatment may enter guidelines for treating a given problem. You may be familiar with this design in terms of new pharmaceutical drugs: there’s a pill with the actual medication and there’s a placebo or “sugar pill.” A similar process had been adopted to therapeutic treatments. To illustrate, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced1 is considered the gold standard treatment for eating disorders2–4. The idea behind this treatment is that over-valuation of weight and shape (e.g., thoughts like “I must be thinner,” “I will be rejected if I gain weight”) cause eating disorder behaviors (e.g., restrictive eating, binge-eating, purging, driven exercise). These behaviors fuel the eating disorder thoughts, and thus create a cycle. Therefore, when an individual starts Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced and engages in processes such as regular eating, evaluating thoughts, and weekly weighing, they learn to invest in other values (such as friendships) and manage uncomfortable emotions in healthier ways. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced is the leading evidence-based treatment for eating disorders. As several studies have replicated these findings, guidelines suggest that this approach is the frontline treatment for eating disorders2–4. Researching Groups and Treating Individuals Unlike many medical diseases, in psychology, we often don’t know what causes a disorder, and perhaps there are different causes that drive a disorder across individuals. The response rate across evidence-based treatments for a range of concerns is up to 50%5–7. This finding means that our best treatments work for half of people. There are many reasons why treatments are generally effective for half of people . One reason that may explain these rates are RCTs have historically compared groups, not individuals. For example, researchers average symptom scores for the group who received treatment and test whether it differs from the average symptom scores for the group who did not receive treatment. For example, do eating disorder symptoms decrease more in a group who received cognitive behavioral therapy versus the group who received dialectical behavioral therapy. There is value in studying groups. A group-level approach is important because it can be helpful for psychologists to know what “generally works.” The shortcoming is that RCTs risk assuming people with a disorder are the same (e.g., experience the same symptoms; respond to treatment in the same way), which often results in a one-size-fits all treatment8. Yet, therapy is often delivered to an individual. The decision to treat the individual is intuitive. However, despite decades-old calls to study individuals, research has largely remained at investigating groups[1]. On one hand this reality is discouraging because we still don’t know how to best treat individuals. On the other hand, work investigating individuals is growing. Though this topic is relevant to most mental disorders, the rest of this post will describe why and how our lab is centering the individual in studying eating disorders and developing personalized treatments for eating disorders. [1] Note: There has been some work investigating treatment at the individual level over the years, but this work lags in comparison. Further, the methods have not been that rigorous until recently due to smart phones and watches. Why study eating disorders within an individual? Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are eating disorders that enter the mainstream, but there are more than two eating disorders, such as, binge eating disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED). Most of these disorders share common features, such as weight and shape disturbance, restricting food intake, binge eating, and compensatory behaviors. Despite these similarities, eating disorders look very different across diagnoses (e.g., bulimia nervosa vs ARFID) and within one disorder (e.g., one person with anorexia nervosa may binge and purge and another person with anorexia nervosa may not)9–11. OSFED is the most common eating disorder diagnosis12 and it captures eating disorder presentations that do not “neatly” fall into other eating disorders. This diagnosis includes people who may meet criteria for anorexia nervosa aside from being underweight, people who would meet criteria for bulimia nervosa but purge one day less a week, people who would meet criteria for ARFID but do not have a nutritional deficiency, etc. Further, co-occurring concerns, such as anxiety, depression, substance use, etc., may also influence how a person struggles with eating, weight, and shape concerns. What this suggests to us is eating disorders can look very different from person to person! This reality causes challenges for scientists and clinicians who are left asking questions like, “Where do we start treatment?” “What treatment will be most effective at relieving symptoms and most efficient in terms of time and money?” The answers to these questions may depend on the person, which is why our lab is studying personalized approaches to eating disorders. How do we study eating disorders within one person? To find an effect of treatment, we need observations, usually lots of observations. Many observations help researchers not only gather enough observation for analyses, but it also provides us with rich detail about how eating disorders look so that we can develop and implement the best treatments. When studying groups, we gather observations by recruiting a large number of participants. When studying individuals, we gather observations by asking individual participants to report on symptoms many times a day for several days. These symptoms are obtained from surveys delivered to individuals’ mobile devices. We then have lots of information on one person, so then for each person, we have something that looks like this: From the example above, what we have is a sheet for one person (ID001) reporting on their urges to binge eat, urges to purge, and current anxiety. What we see is that for this person, their urges to engage in eating disorder symptoms, as well as the anxiety they are experiencing within a given moment, change over the course of the day (e.g., anxiety ranges from 33 at 8AM to 93 at 9 PM on March 1). What we can then do is apply statistics to model how these different symptoms relate to each other across time. In this figure, the green arrows represent positive relationships, and the red arrow represents a negative relationship. For instance, increased urge to binge eat is related to increased urge to purge. However, an increased urge to purge is related to less anxiety. By modeling a person’s specific symptom relationships, we can use data to help clarify our existing case conceptualizations and determine which intervention maps onto symptoms that may be driving an individual’s distress11. For this person, we may wonder if purging serves the purpose to reduce anxiety, which may be caused from binge eating and/or weight and shape-related concerns.

Regardless, you can imagine how these relationships vary across people. By studying the individual, we are moving toward personalized treatment, or “precision medicine,” so that your treatment makes sense for you, rather than what *might* work for the group. As it stands, our gold-standard treatments work for 50% of individuals with eating disorders. I think researchers and clinicians can do better by you, participants and/or patients. Our lab find promise in using individual approaches to data analysis to inform personalized treatment to do just that. Our preliminary data using a data-driven approach to personalized treatment shows reductions of eating disorder symptoms after treatment, as well as one-year post-treatment for the individual13. What this means is that the improvements in eating disorder symptoms may be maintained over long stretches time. When the current state of the field shows that half of individuals achieve full recovery, with many experiencing diagnostic cross-over (e.g., meeting criteria for anorexia nervosa and later meeting criteria for bulimia nervosa), we hope that these insights offer a glimmer of hope that the eating disorder field is progressing while keeping you at the center of our work. How you can play a role in advancing eating disorder treatments We are launching a new treatment study for eating disorders that tests a Personalized Treatment approach versus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Enhanced. Participants enrolled in this study will receive 20 sessions of free individual therapy for their eating disorder. To learn more about this study and see if you are eligible, please click this link which will direct you to our website. References 1. Fairburn, C. G. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. (Guilford Press, 2008). 2. Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z. & Shafran, R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a ‘transdiagnostic’ theory and treatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 41, 509–528 (2003). 3. Fairburn, C. G. et al. A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 70, 64–71 (2015). 4. Murphy, R., Straebler, S., Cooper, Z. & Fairburn, C. G. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 33, 611–627 (2010). 5. Carter, J. C., Blackmore, E., Sutandar-Pinnock, K. & Woodside, D. B. Relapse in anorexia nervosa: a survival analysis. Psychol. Med. 34, 671–679 (2004). 6. Trivedi, R. 1975-, United States. Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Services Research and Development Service, Durham VA Medical Center, & Duke University Evidence-based Practice Center. Evidence synthesis for determining the efficacy of psychotherapy for treatment resistant depression. (Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, 2009). 7. Batelaan, N. M. et al. Risk of relapse after antidepressant discontinuation in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of relapse prevention trials. The BMJ 358, j3927 (2017). 8. Spring, B. Evidence-based practice in clinical psychology: What it is, why it matters; what you need to know. J. Clin. Psychol. 63, 611–631 (2007). 9. Forbush, K. T. et al. Understanding eating disorders within internalizing psychopathology: A novel transdiagnostic, hierarchical-dimensional model. Compr. Psychiatry 79, 40–52 (2017). 10. Levinson, C. A. et al. Personalized networks of eating disorder symptoms predicting eating disorder outcomes and remission. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53, 2086–2094 (2020). 11. Levinson, C. A. et al. Using individual networks to identify treatment targets for eating disorder treatment: a proof-of-concept study and initial data. J. Eat. Disord. 9, 147 (2021). 12. Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G. & Tavolacci, M. P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 1402–1413 (2019). 13. Levinson, C. A. et al. Longitudinal group and individual networks of eating disorder symptoms in individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci.

0 Comments

|

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed