|

By Claire Cusack, B.A., Lab Manager “If you would only stop thinking, you would be much happier” ―Pavilion of Women, Pearl S. Buck Individuals with eating disorders are often bombarded with negative thoughts, both eating disorder specific and general. Some thoughts may resemble worry and others rumination. Yes, there is a difference between worry and rumination! Though worry and rumination are similar negative thinking patterns (Fresco et al., 2002),

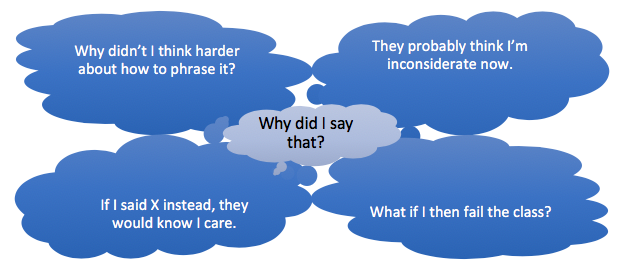

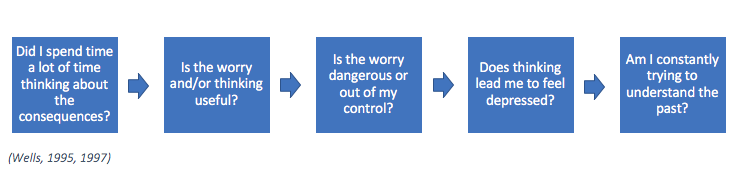

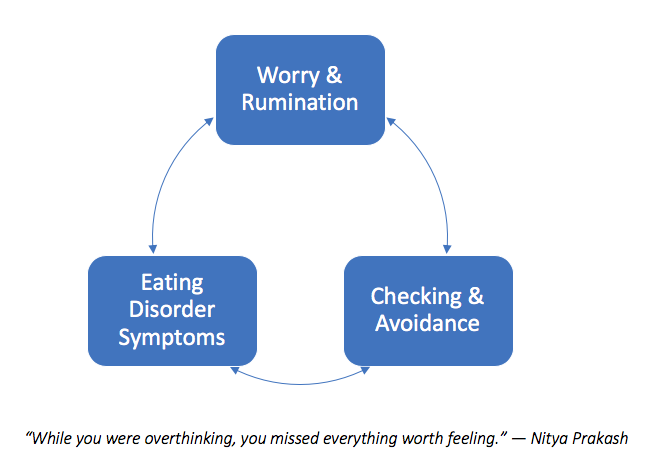

Worry is usually repetitive negative thoughts about the future, and rumination is usually repetitive negative thoughts about the past. In other words, worry is characterized by “What if’s” and rumination is characterized by “Why’s.” What if I fail? Why did I say that? What if I gain weight? Why can’t I eat normally? At some level, everyone worries and ruminates, even those without eating disorders, and worry and rumination may be adaptive! For instance, concern about an upcoming test may motivate you to study, to reflect on a time that things didn’t go as well as you hoped, or may help you do things differently next time. However, for individuals with eating disorders who also show anxious and depressive symptoms, the thoughts may become unhelpful (Smith et al., 2018). This is where you may get stuck. Have you ever kept circling over an event and have gotten nowhere? Have you asked yourself things like: Repeating these thoughts may make them seem true or like your fears are inevitable. The good news is that 93% of worries do not come true (LaFreniere & Newman, 2020). When worries do come true, it’s often because we make them come true or what happens turns out to not be as bad as we thought it would. For example, before you know it, you’ve spent so much time thinking that you haven’t checked in with your friend about how they actually interpreted what you said. Or, you’ve spent so much time worrying about failing, that you didn’t study for the test. These sorts of behaviors in response to thoughts may actually cause a rift in the friendship or a low grade. Indeed, it is easy to get trapped in these cyclical negative thought patterns and believe them. These thoughts may make it more difficult to concentrate, do daily activities, or focus on the present (Paperogiou, 2006). Moreover, you may believe that these thoughts are valuable (Behar et al., 2009) and help you (Ellis & Hudson, 2010), such as by avoiding weight gain, or make you feel better (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006). What makes rumination even more insidious is it doesn’t always appear like “negative” or brooding thoughts. Reflecting on food, weight, and shape can lead to eating disorder symptoms just like brooding does (Cowdrey & Park, 2012). An example may be writing down food intake, thinking about it, and analyzing it (Cowdrey & Park, 2011). Though not obviously problematic, this type of behavior encourages repetitive (and unrealistic) negative thinking that takes you out of the present moment. How do I know if my thoughts are helpful or not? “Yes” to these questions may suggest your thinking patterns are not serving you. When worry and rumination become unmanageable, people often engage in corrective responses (Rawal et al., 2011). These responses may look like seeking reassurance (e.g., weighing or body checking) and attempting to avoid the negative thoughts (Cowdrey & Park, 2012), which ultimately increases eating disorder symptoms (Rawal et al., 2011). The reverse may be true too, where eating disorder symptoms trigger worry and rumination, thus circling back to more eating disorder behaviors (Smith et al., 2018). The repetitive negative thoughts, eating disorder behaviors, and management of both are exhausting. So, what can you do about it?

While you may currently be in the throes of an endless loop of worry, depression, and symptoms, you can put a pin it and break the cycle. It may seem counter-intuitive, yet approaching and accepting your thoughts can help you find a way out. This means inviting curiosity into your thoughts. When a thought (or series of thoughts) pops into your head, instead of accepting them as fact, notice them, acknowledge them, and try saying “Maybe, maybe not.” This lessens their power. You might wonder, “Why do I need to approach my thoughts and emotions when I am already constantly thinking?” Certainly, worry and rumination can be near constant and thus, may not seem like avoidance. Ironically, they are forms of avoidance. So, how do you approach a thought or feeling when you feel like you’re already doing that, and in fact, can’t avoid thinking? Surprisingly, this does not involve changing the content of your thoughts, but rather changing the thought processes (Ellis & Hudson, 2010; Watkins et al., 2007). Simply put, you don’t have to change what you’re thinking about, but how you’re thinking about it. Here are some suggestions when encountering repetitive negative thoughts:

When giving a presentation at school or at work, you might slip on your words. If you catch yourself wondering “Why did I do that? Did they notice? Everyone must think I’m incompetent,” you can take a step back from the thoughts by acknowledging them. “I think that others think less of me because I made a mistake.” Taking a step into the feelings may look like, “I feel embarrassed.” Remembering the big picture could look like, “Even though I messed up a few words, the audience was still able to follow my presentation. Everyone makes mistakes.”

Here are three take-aways:

This doesn’t mean you won’t think negative thoughts or experience uncomfortable emotions. This is a hope that by shifting the way you think, you can not only face uncomfortable emotions, but you create room to feel the happier ones, too.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed