|

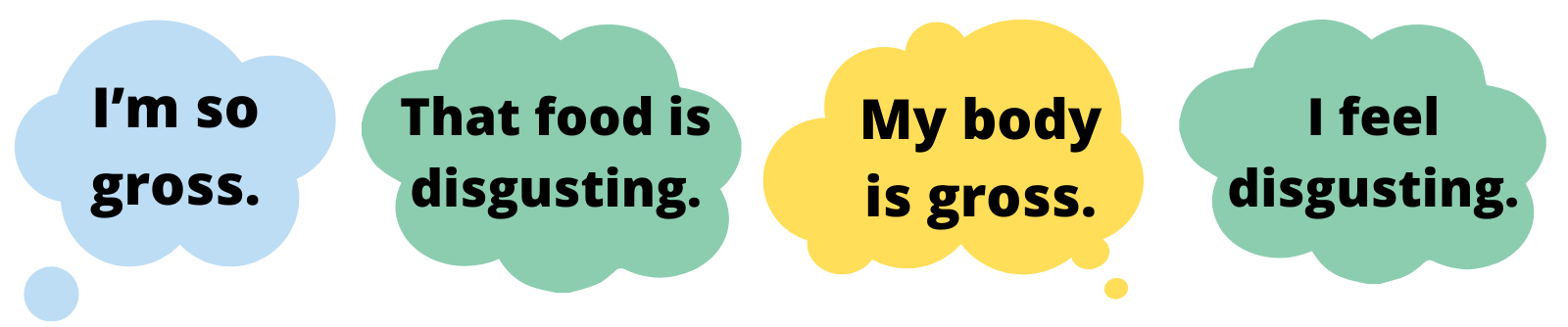

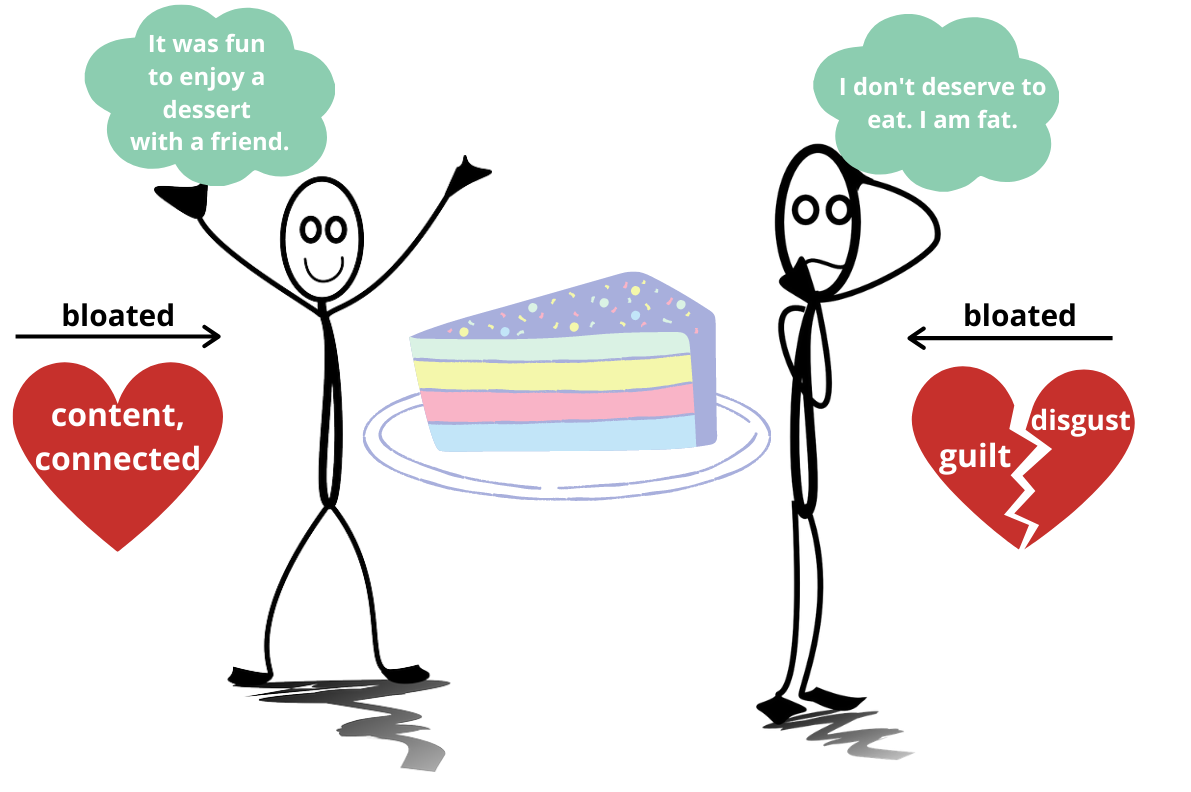

By Claire Cusack, M.A., Lab Manager, Incoming 1st year graduate student Ew. Gross. Ick. Yuck. People describe an array of things as gross, repulsive, or disgusting.  Disney Pixar's Inside Out, 2015 Disney Pixar's Inside Out, 2015 But what is disgust, and what does it have to do with eating disorders? At its base, disgust means “bad taste.” Disgust is a tool that may keep us alive by helping us to reject, spit out, and avoid food and substances may cause us disease and death (1). Disgust is a basic emotion characterized by a facial reaction (for instance, scrunching the nose), physiological sensation (e.g., nausea), and a visceral feeling of revulsion. As you’d expect, or have perhaps experienced, it is typically followed by avoidant behavior, such as moving backward, covering your nose, spitting something out, or closing your eyes. With this understanding, disgust may help us. For example, if you spit out poisoned food because it tastes bad, it may save your life! How does disgust run amok? Though disgust may serve as a protective function for our bodies, things can go awry in eating disorders (2,3) That is, your brain sends a false alarm that there is a threat, when in actuality there is none. Similar to anxiety, you may interpret a food as disgusting and overestimate the harm caused by it (4). Over time, your brain may pair a certain food with the feelings of disgust, and you may avoid foods that are not harmful but necessary for your survival. This pathway is difficult to change for a couple reasons: 1) Your brain’s resources are dedicated to prioritizing “safety,” and 2) Avoidance feels good (5).  What sets off the false alarm? This likely varies person to person, but there are some common triggers that may signal disgust. First, disgust is culturally bound (6) and tied to related ideas of morality (4). As a society, we decide what is “disgusting,” and when we engage in behaviors that elicit disgust, we then attach a good or bad value judgment to it. While fat is important for our survival, we may falsely learn that fat is bad or disgusting. So we may learn to believe that certain food or certain body sizes and shapes are good or bad due to us learning that fatness is disgusting (incorrectly; 7). Another player in setting off the disgust alarm are physical sensations (8-10). These could include feelings of bloating, tightness in stomach, nausea, or other unpleasant bodily sensations or experiences. These bodily sensations can be confused as feelings (11). Importantly, making sense of these sensations relies on our ability to detect and appraise sensations (12). For instance, for our survival, we first need to recognize a feeling and then evaluate it (e.g., harmful or safe). Below, we see how two different people can process the same event (eating cake) differently in terms of thoughts (it was fun vs. I shouldn’t have), emotions (connected vs. guilt), and physical sensations (e.g., feeling bloated). It can be challenging to integrate physical feelings, emotions, and thoughts. It’s especially difficult when you don’t trust your body (13). It makes sense to evaluate food as disgusting if you don’t believe your body will take care of you. However, food is only one aspect of disgust and eating disorders. Individuals with eating disorders find an array of things disgusting, such as food, weight gain, their body, but disgust can generalize beyond eating disorder content (14). The line between body and self can become blurred (15). In other words, individuals with eating disorders may also feel disgusted by who they are (8, 16). It’s so tempting to accept these thoughts and feelings at face value, but not all thoughts are true, in fact most are not. The bottom line: your body is not disgusting, and neither are you.

Ways to work through false alarm disgust: 1.) Identify what’s disgusting. Work with your therapist to identify and rank what is disgusting from least to most disgusting (17).You may work together to plan exposures to work through feelings of disgust. 2.) Learn your values. What are your values? Family, friends, school or work, spiritual growth, social justice, kindness, or maybe something else? You can write these down. Now, when you look at the disgusting list, do you believe the things on the disgust list above are disgusting or does your eating disorder? With this awareness, you may be able to make decisions that could still feel gross, but actually align with your values (18). 3.) Create opportunities for new learning. This suggestion builds on #1 and #2. If physical sensations such as drinking water, following your meal plan, eating foods that feel heavy in your stomach, or something else feels disgusting to you, and if they are a false alarm disgust, then press through and approach them. One way to approach false alarms is through interoceptive exposures. An interoceptive exposure is where you intentionally engage in activity that causes you to feel a particular sensation in your body. These exposures may help distress associated with your eating disorder (8,9,19). Let’s say feeling full disgusts you because you think that the sensation of fullness means you are gaining weight. You could drink water and sit with the bodily and emotional sensations that arise (or work with your therapist to do this). Mirror exposures may be useful for working through the body parts you find disgusting (20). This involves looking at the parts of your body that bring up feelings of disgust for you. These exposures can be practiced in therapy sessions and between therapy sessions. The goal is not to feel less disgusting but learn that you can handle this feeling. “You can be still and still moving. Content even in your discontent.” – Ram Dass 4.) Notice when the disgust alarm is false. Mindfulness exercises and meditation to increase awareness and accuracy of body signal interpretation (21, 22). For example, breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, or 5-4-3-2-1 (5 things you can see, 4 things you can touch, 3 things you can hear, 2 things you can taste, and 1 thing you can smell) can bring you to the present moment. Then, you may be better able to answer questions like, “Is this actually disgusting? Am I safe? Should I avoid this? Does that match my values?” 5.) You are more than your body. You may feel disgust in or about your body or body areas. This does not mean you are disgusting, because feelings are not always accurate. The feeling of disgust may be a false alarm, but it is felt as very real. Two truths can exist at once. A feeling (and/or a thought) is not a fact, so challenge these feelings/thoughts by asking yourself questions rather than accepting feelings as absolute truths. Is there evidence to suggest you are not disgusting? For example, did you help a friend? Or maybe you were kind to a coworker or peer? 6.) Fight fatphobia. Create new culture that values and celebrates all body sizes and shapes, including yours. Ask yourself, “Where did I learn this was disgusting?” If you’re interested in fighting fatphobia and learning more about diet culture, let us know by emailing [email protected] – We have a new treatment study coming soon focused on this very issue! References [1] P. Rozin and A. E. Fallon, “A perspective on disgust,” Psychol. Rev., vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 23–41, 1987, doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.1.23. [2] T. Harvey, N. A. Troop, J. L. Treasure, and T. Murphy, “Fear, disgust, and abnormal eating attitudes: A preliminary study,” Int. J. Eat. Disord., vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 213–218, 2002, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10069. [3] B. O. Olatunji and D. McKay, Disgust and its disorders: Theory, assessment, and treatment implications. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, 2009, pp. xvii, 324. doi: 10.1037/11856-000. [4] J. M. Tybur, D. Lieberman, R. Kurzban, and P. DeScioli, “Disgust: Evolved function and structure,” Psychol. Rev., vol. 120, no. 1, pp. 65–84, 2013, doi: 10.1037/a0030778. [5] T. Hildebrandt et al., “Testing the disgust conditioning theory of food-avoidance in adolescents with recent onset anorexia nervosa,” Behav. Res. Ther., vol. 71, pp. 131–138, Aug. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.008. [6] P. Rozin and J. Haidt, “The domains of disgust and their origins: contrasting biological and cultural evolutionary accounts,” Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 367–368, Aug. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.001. [7] B. O. Olatunji and C. N. Sawchuk, “Disgust: Characteristic Features, Social Manifestations, and Clinical Implications,” J. Soc. Clin. Psychol., vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 932–962, Nov. 2005, doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.7.932. [8] K. Bell, H. Coulthard, and D. Wildbur, “Self-Disgust within Eating Disordered Groups: Associations with Anxiety, Disgust Sensitivity and Sensory Processing,” Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc., vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 373–380, Sep. 2017, doi: 10.1002/erv.2529. [9] J. F. Boswell, L. M. Anderson, and D. A. Anderson, “Integration of interoceptive exposure in eating disorder treatment,” Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract., vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 194–210, 2015, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12103. [10] M. Plasencia, R. Sysko, K. Fink, and T. Hildebrandt, “Applying the disgust conditioning model of food avoidance: A case study of acceptance-based interoceptive exposure,” Int. J. Eat. Disord., vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 473–477, 2019, doi: 10.1002/eat.23045. [11] O. G. Cameron, “Interoception: The Inside Story—A Model for Psychosomatic Processes,” Psychosom. Med., vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 697–710, Oct. 2001. [12] S. S. Khalsa et al., “Interoception and mental health: A roadmap,” Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 501–513, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004. [13] T. A. Brown et al., “Body mistrust bridges interoceptive awareness and eating disorder symptoms,” J. Abnorm. Psychol., vol. 129, no. 5, pp. 445–456, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1037/abn0000516. [14] L. M. Anderson, H. Berg, T. A. Brown, J. Menzel, and E. E. Reilly, “The Role of Disgust in Eating Disorders,” Curr. Psychiatry Rep., vol. 23, no. 2, p. 4, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01217-5. [15] J. Moncrieff-Boyd, S. Byrne, and K. Nunn, “Disgust and Anorexia Nervosa: confusion between self and non-self,” Adv. Eat. Disord., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 4–18, Jan. 2014, doi: 10.1080/21662630.2013.820376. [16] J. R. Fox, N. Grange, and M. J. Power, “Self-disgust in eating disorders: A review of the literature and clinical implications,” in The Revolting Self: Perspectives on the Psychological, Social, and Clinical Implications of Self-Directed Disgust, P. A. Powell, P. G. Overton, and J. Simpson, Eds. London: Karnac Books, 2015, pp. 167–186. [17] R. M. Butler and R. G. Heimberg, “Exposure therapy for eating disorders: A systematic review,” Clin. Psychol. Rev., vol. 78, p. 101851, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101851. [18] C.-Q. Zhang, E. Leeming, P. Smith, P.-K. Chung, M. S. Hagger, and S. C. Hayes, “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Health Behavior Change: A Contextually-Driven Approach,” Front. Psychol., vol. 8, 2018, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02350. [19] E. E. Reilly, L. M. Anderson, S. Gorrell, K. Schaumberg, and D. A. Anderson, “Expanding exposure-based interventions for eating disorders,” Int. J. Eat. Disord., vol. 50, no. 10, pp. 1137–1141, Oct. 2017, doi: 10.1002/eat.22761. [20] T. C. Griffen, E. Naumann, and T. Hildebrandt, “Mirror exposure therapy for body image disturbances and eating disorders: A review,” Clin. Psychol. Rev., vol. 65, pp. 163–174, Nov. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.08.006. [21] J. Gibson, “Mindfulness, Interoception, and the Body: A Contemporary Perspective,” Front. Psychol., vol. 10, 2019, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02012. [22] P. Lattimore, B. R. Mead, L. Irwin, L. Grice, R. Carson, and P. Malinowski, “‘I can’t accept that feeling’: Relationships between interoceptive awareness, mindfulness and eating disorder symptoms in females with, and at-risk of an eating disorder,” Psychiatry Res., vol. 247, pp. 163–171, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.022.

1 Comment

|

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed