Nine Truths Your Eating Disorder Does Not Want You to Know: An Eating Disorder Therapist Perspective11/23/2020 By: Cheri A. Levinson, PhD | EAT Lab Director

1. Food will not hurt you. In fact, food is your route to healing. 2. Your anxiety, fear, guilt and other emotions will not hurt you. Embrace your emotions and you will start to break free. 3. Your size does not matter. It does not matter. It does not matter. Size does not define who you are or what you can do with your life. 4. Becoming thinner will not make you happy. Running more will not make you happy. Restricting more will not make you happy. Letting go of your eating disorder is the only pathway to happiness. 5. You can and will survive if someone judges you. When it comes down to what matters, people do not care about how big, thin, fat etc. you are. People worry more about themselves than other people. And if they do judge you on how you look, first, it won’t impact your life and second, you probably don’t want to be around them anyway. 6. The more you eat the more energy you will have. The more energy you have the more you can actually enjoy life. 7. You are a unique and special person who does enough and is enough just by being you. 8. Everyone deserves to eat. That voice in the back of your head telling you otherwise is wrong. 9. Diet culture is an illusion steeped in patriarchy. It’s society’s way of holding you back. It profits large corporations and a corrupt wellness industry. Don’t let it win. Fight back.

0 Comments

By Caroline Christian, M.S.

3rd Year Graduate Student In our society, there are codes for how we treat one another. Imagine you are watching as someone walks up to a stranger and says, “Oh my gosh, you are so fat, there is no way anyone will ever love you.” What would your reaction be? Shock? Horror? Disbelief? You may even feel the need to walk up to the person and let them know that is not acceptable, or to comfort the other person. Or imagine saying to a friend, “Ew, your body looks gross today. You shouldn’t leave the house.” Or imagine if a friend said to you, “You need to lose weight, let’s not eat today.” What would your response be? These are examples of statements you would likely never say, or probably even think, about another person, because it would be rude, hostile, and may even end relationships. So why do we accept these statements when they are said to us by an eating disorder? Individuals with eating disorders experience urges to engage in maladaptive behaviors, which are often driven by eating disorder thoughts. As discussed in the book, “Life without Ed”, by Jenni Schaefer, eating disorder thoughts often feel like another voice or entity (Ed) living in your head, chiming in on how you eat, socialize, and view your body (if unfamiliar with the eating disorder voice, you can read more here). The examples, “you are so fat,” “you shouldn’t leave the house today,” and “you need to lose weight” are just a few Ed thoughts that individuals with eating disorders may feel constantly bombarded with, especially around meal times, social gatherings, or situations involving seeing one’s body. Even if you don’t have an eating disorder, you likely still hear thoughts like this from time to time when looking in the mirror, trying on clothes, comparing yourself to friends, or eating at a restaurant. Although not typically accepted towards others, having critical thoughts about one’s own body and eating habits is so engrained in our society. We are taught that these self-critical thoughts are there for a reason: to motivate us to be “healthy,” to be the best version of ourselves, to be liked, and to have the most friends. These myths leading to shame, unhealthy weight-loss behaviors, and the impossible pursuit of perfection can hold us back from self-love and living life to the fullest. We are told we need to hate ourselves in order to motivate positive change, but in reality, the best motivator to want to take care of yourself is to love and accept yourself exactly as you are. Below are tips from evidence-based therapies for eating disorders, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder that may help you respond to these intrusive eating disorder thoughts that people of all backgrounds experience. The severity of these thoughts may widely differ for all people, but these tips can be helpful for folks that are young and old, men, women, and gender minorities, and people with and without eating disorders. For individuals at various stages of eating disorder recovery, we hope this is a helpful supplement or refresher, but strongly recommend working with an eating disorder specialist to practice responding to Ed thoughts. Resources for seeking treatment are included the very bottom of this page. 1. Practice logging thoughts to notice when Ed thoughts come up. The first step in responding to unhelpful thoughts is to notice when they arise. Starting a log or diary of thoughts can help identify when thoughts come up, if there are patterns in what triggered the thought, and how these thoughts impact your day. For example, you may notice you have self-critical thoughts about your body when you look in the mirror, and that these thoughts contribute to shame and make it harder to focus at work. Even just building this awareness can help you reclaim your life from Ed thoughts. It can also help you decide if and when it may be most helpful to use the other skills below. 2. Telling Ed “maybe, maybe not.” One quick response to Ed thoughts is, “Maybe, maybe not.” This skill comes from acceptance-based and exposure-based therapies, and stems from the idea that you can accept uncertainty without having to respond to it with anxiety or unhealthy behaviors. For example, if Ed says, “Nobody will like you because you look fat,” you can say “Maybe nobody will ever like me, but maybe they will.” This dismission of Ed prevents the thought from spiraling and can help you become comfortable with the discomfort of uncertainty. For example, in reality, there may be people in society who judge others based on weight, but ruminative thoughts about the past and worried thoughts about the future don’t have to dictate how you feel in the current moment. 3. Treat yourself like you would treat a friend who heard Ed thoughts. Treating yourself like you would treat a loved one is the primary tenant of self-compassion. As exemplified in the first paragraph, many of us would never say the things Ed tell us to a friend or accept such comments from a stranger. Self-compassion is a great tool to use all the time, but especially when 1) you’re going through a hard time or 2) you feel like you’ve made a mistake. Self-critical thoughts about food and body can be especially loud during these times, so when you hear those thoughts (e.g., “you aren’t good enough”; “you shouldn’t have eaten that”), try to respond to yourself like you would a friend going through that same tough time. For example, if your friend is having Ed thoughts about her body after looking in the mirror, you may compliment her, remind her of other things you like about her, give her a hug, or invite her to do something fun or relaxing. Many people rarely afford the same compassion to themselves. Start to practice directing this kindness inward and see how it may change your outlook. 4. Challenge Ed thoughts. Another tool for responding to these thoughts comes from cognitive-behavioral therapy. Most self-critical thoughts have logical fallacies in them, like assuming something is black-or-white, exaggerating possible negatives, trying to predict the future, or assuming you know what another person may think. If you notice you have a thought that is based on a myth or misconception (try noticing them in the examples above!), you can challenge the thought and replace it with a rational alternative. You can challenge a thought by putting it on trial, and listing evidence (facts, not feelings) that support the statement is true, as well as evidence that contradicts the thought. For example, there probably isn’t much evidence that your friends think you are fat, but a lot of evidence that your friends like you for who you are! Writing out this evidence can help you see the reality of the situation; not just what Ed sees. 5. Let Ed thoughts come and go without changing behaviors. Importantly, self-critical thoughts are usually accompanied with something you should do or change, including unhealthy weight loss behaviors. It can be hard not to let these thoughts motivate you to do things that may be harmful or hurtful. However, there are several skills you can use to let these thoughts go, without giving them power or feeling like you must engage in behaviors. One example is the “leaves on a stream” meditation. In this meditation, you picture yourself in a wooded area by a stream. You picture the leaves from the trees around you as they fall from the trees, land on the stream, and slowly get swept away. When doing this meditation, as thoughts come up, especially unhelpful Ed thoughts, you can acknowledge the thought, place it on a leaf, and slowly watch it float away. There are also versions of this meditation where you put your thoughts on clouds, or a conveyor belt – whatever is best for you! The idea behind this meditation is that you can experience thoughts without valuing or buying into them, and that the thought does not have to continue to stay in your mind. Practicing this meditation can help you get better at letting go and saying no to Ed thoughts. 6. Model these skills for loved ones. It is important to note that most people have self-critical thoughts and varying levels of practice responding to them. When interacting with friends and loved ones, it can be helpful to spread positive messages about food and body image and be mindful of saying things that enhance other’s Ed thoughts. Even saying critical thoughts about yourself, like “Do I look fat in this dress?” is a form of fat talk that can influence other’s perceptions of themselves. Instead, try to be self-compassionate, present-focused, and nonjudgmental of thoughts even when you are around others. By doing this, you may help others that have similar struggles with self-criticism or intrusive Ed thoughts. You can read more about how to spread positive food and body messages in this blog! Responding to these self-critical thoughts about food and body image is not easy at first, whether you have an eating disorder or not. However, being aware of and responding to these thoughts can give them less power in your life, opening you up to a fuller life with self-compassion, self-acceptance, and present-focused awareness. As thoughts like, “I should lose weight so people think I am attractive,” or “I look so bloated and gross right now” come up in real life, let yourself replace these thoughts with rational thoughts, like, “My loved ones care about me, not my weight” and “It is normal that my body shape fluctuates.” Even though it may feel difficult at first, I encourage you to practice these responses and find the ones that are most helpful for you. Resources for seeking treatment: https://www.edreferral.com/ https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/help-support/contact-helpline https://map.nationaleatingdisorders.org/ (for those in Louisville or Kentucky) https://www.louisvillecenterforeatingdisorders.com/ By Claire Cusack, B.A., Lab Manager “If you would only stop thinking, you would be much happier” ―Pavilion of Women, Pearl S. Buck Individuals with eating disorders are often bombarded with negative thoughts, both eating disorder specific and general. Some thoughts may resemble worry and others rumination. Yes, there is a difference between worry and rumination! Though worry and rumination are similar negative thinking patterns (Fresco et al., 2002),

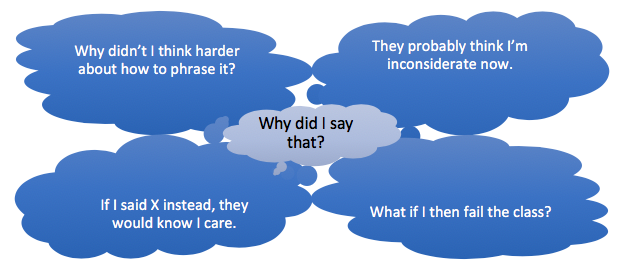

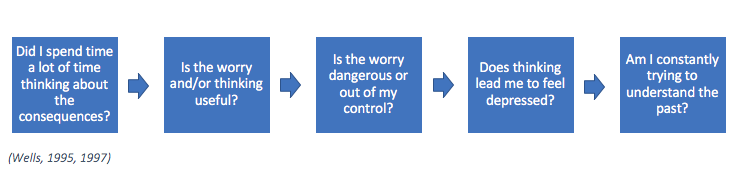

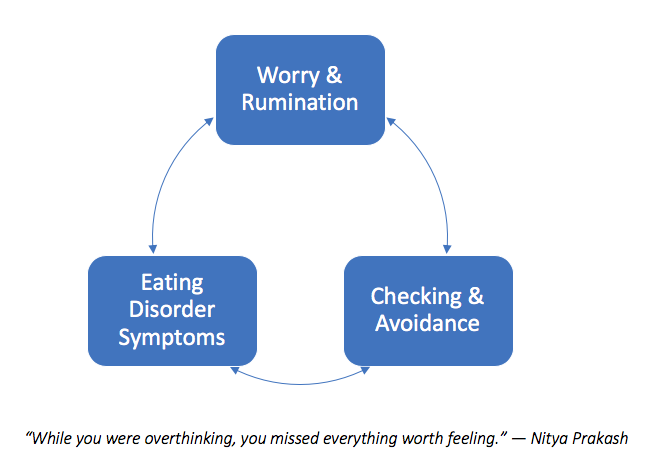

Worry is usually repetitive negative thoughts about the future, and rumination is usually repetitive negative thoughts about the past. In other words, worry is characterized by “What if’s” and rumination is characterized by “Why’s.” What if I fail? Why did I say that? What if I gain weight? Why can’t I eat normally? At some level, everyone worries and ruminates, even those without eating disorders, and worry and rumination may be adaptive! For instance, concern about an upcoming test may motivate you to study, to reflect on a time that things didn’t go as well as you hoped, or may help you do things differently next time. However, for individuals with eating disorders who also show anxious and depressive symptoms, the thoughts may become unhelpful (Smith et al., 2018). This is where you may get stuck. Have you ever kept circling over an event and have gotten nowhere? Have you asked yourself things like: Repeating these thoughts may make them seem true or like your fears are inevitable. The good news is that 93% of worries do not come true (LaFreniere & Newman, 2020). When worries do come true, it’s often because we make them come true or what happens turns out to not be as bad as we thought it would. For example, before you know it, you’ve spent so much time thinking that you haven’t checked in with your friend about how they actually interpreted what you said. Or, you’ve spent so much time worrying about failing, that you didn’t study for the test. These sorts of behaviors in response to thoughts may actually cause a rift in the friendship or a low grade. Indeed, it is easy to get trapped in these cyclical negative thought patterns and believe them. These thoughts may make it more difficult to concentrate, do daily activities, or focus on the present (Paperogiou, 2006). Moreover, you may believe that these thoughts are valuable (Behar et al., 2009) and help you (Ellis & Hudson, 2010), such as by avoiding weight gain, or make you feel better (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006). What makes rumination even more insidious is it doesn’t always appear like “negative” or brooding thoughts. Reflecting on food, weight, and shape can lead to eating disorder symptoms just like brooding does (Cowdrey & Park, 2012). An example may be writing down food intake, thinking about it, and analyzing it (Cowdrey & Park, 2011). Though not obviously problematic, this type of behavior encourages repetitive (and unrealistic) negative thinking that takes you out of the present moment. How do I know if my thoughts are helpful or not? “Yes” to these questions may suggest your thinking patterns are not serving you. When worry and rumination become unmanageable, people often engage in corrective responses (Rawal et al., 2011). These responses may look like seeking reassurance (e.g., weighing or body checking) and attempting to avoid the negative thoughts (Cowdrey & Park, 2012), which ultimately increases eating disorder symptoms (Rawal et al., 2011). The reverse may be true too, where eating disorder symptoms trigger worry and rumination, thus circling back to more eating disorder behaviors (Smith et al., 2018). The repetitive negative thoughts, eating disorder behaviors, and management of both are exhausting. So, what can you do about it?

While you may currently be in the throes of an endless loop of worry, depression, and symptoms, you can put a pin it and break the cycle. It may seem counter-intuitive, yet approaching and accepting your thoughts can help you find a way out. This means inviting curiosity into your thoughts. When a thought (or series of thoughts) pops into your head, instead of accepting them as fact, notice them, acknowledge them, and try saying “Maybe, maybe not.” This lessens their power. You might wonder, “Why do I need to approach my thoughts and emotions when I am already constantly thinking?” Certainly, worry and rumination can be near constant and thus, may not seem like avoidance. Ironically, they are forms of avoidance. So, how do you approach a thought or feeling when you feel like you’re already doing that, and in fact, can’t avoid thinking? Surprisingly, this does not involve changing the content of your thoughts, but rather changing the thought processes (Ellis & Hudson, 2010; Watkins et al., 2007). Simply put, you don’t have to change what you’re thinking about, but how you’re thinking about it. Here are some suggestions when encountering repetitive negative thoughts:

When giving a presentation at school or at work, you might slip on your words. If you catch yourself wondering “Why did I do that? Did they notice? Everyone must think I’m incompetent,” you can take a step back from the thoughts by acknowledging them. “I think that others think less of me because I made a mistake.” Taking a step into the feelings may look like, “I feel embarrassed.” Remembering the big picture could look like, “Even though I messed up a few words, the audience was still able to follow my presentation. Everyone makes mistakes.”

Here are three take-aways:

This doesn’t mean you won’t think negative thoughts or experience uncomfortable emotions. This is a hope that by shifting the way you think, you can not only face uncomfortable emotions, but you create room to feel the happier ones, too. Brenna Williams, B.A.

“To be beautiful means to be yourself. You don’t need to be accepted by others. You need to accept yourself.” – Thich Nhat Hanh When you look in the mirror, what do you think about your body? How do you picture yourself in your mind? Do you feel comfortable with your body shape, or do you feel self-conscious about the way your body looks? Do you think you have a realistic perception of your body, or is the way you see your body distorted? The way you answer these questions represents your body image. Body image is formally defined as how we feel about our own bodies and our physical appearance. People with a positive body image have realistic perceptions about their bodies. They also accept their bodies or feel comfortable in their own bodies. On the other hand, people with a negative body image have distorted perceptions of their bodies, and they feel shameful, anxious, or self-conscious about their bodies. In other words, people with a negative body image do not see their bodies realistically and they are dissatisfied with their bodies. If you have a negative body image, you’re not alone! Most people have a negative body image, with up to 72% of women and 61% of men report being unsatisfied with their bodies (Fiske et al., 2014). Having a negative body image can impact our mental health. For instance, body dissatisfaction is related to lower self-esteem (Tiggeman, 2005), depression (Keel et al., 2001), and disordered eating (Goldfield et al., 2010). The good news is that body dissatisfaction and negative body image do not have to be permanent, and we do not have to change our bodies to like them. Furthermore, you don’t have to like or love your body to have a positive body image! Having a positive body image can involve simply accepting our bodies as they are in the present moment and not letting how we feel about our bodies get in the way of doing the things we enjoy. We can learn to accept and appreciate our bodies as they are right now. Loving or liking our bodies is not necessary. By changing our behaviors and our perspectives we can promote a positive body image in both ourselves and society. Promoting a Positive Body Image in OURSELVES:

Promoting a Positive Body Image in SOCIETY:

Positive Body Image Resources Please share your own ideas of how to promote a positive body image in both ourselves and society in the comments. We would love to hear your suggestions! By Caroline Christian- Second Year Graduate Student

There is a lot of misinformation and misunderstanding about eating disorders in our society, which can make it difficult to get accurate information about what eating disorders are, and what they look like. Stigma, stereotypes, and poor communication from eating disorder specialists have led to a lack of awareness of the reality of eating disorders. Getting educated about eating disorders can help one learn how to best support a loved one with an eating disorder, help individuals stay motivated in recovery, or help with speaking out against institutions and policies that are harmful for individuals with eating disorders. Here I provide and discuss some statistics and facts about eating disorders based on empirical research, both in the United States broadly, and in my home state of Kentucky. Eating disorders (and disordered eating) are prevalent.

Eating disorders are (increasingly) prevalent in adolescents.

Eating disorders are chronic.

Eating disorders frequently co-occur with other mental and physical health problems.

Eating disorders are difficult to treat.

Eating disorders are underfunded.

Eating disorders are a silent epidemic in Kentucky crucially in need of resources.

These statistics and facts reflect the rather bleak current state of eating disorders. But there is hope! If you are feeling helpless or pessimistic about eating disorders, there are things you can do to help change enact positive change!

By Brenna Williams, Second Year Graduate Student

Happy New Year! It’s a new decade, which means that everyone is thinking about what they want to do in 2020. Because of this, I wanted to talk about the way that we treat ourselves, and how this may impact our own lives. Let’s start this decade off right! When you make a mistake or are going through a difficult time, how do you talk to yourself? What do you say to yourself? What is your tone of voice? Now, think about what happens when one of your close friends makes a mistake or is going through a difficult time. How do you talk to your friend? What do you say to them? What is your tone of voice? When answering these questions, most people find that they talk to their close friend in a much different manner than how they talk to themselves. Generally, we speak kindly to our friends. We reassure them that everything will be okay. Sometimes we tell them we love them despite their mistakes. However, when it comes to ourselves, we are critical. We speak to ourselves harshly, and we may even call ourselves names. We would never talk to another person the way we talk to ourselves. So why are we so self-critical? Self-criticism is normally used as a motivator. For example, imagine that you have arrived home from a long day at work. You had to wake up earlier than normal for a mandatory meeting and got home much later than normal due to traffic. You’re exhausted, so you decide to lay down on the couch for a moment to rest. You need to get up in a few minutes to get ready for dinner with your friend, but you just need a second to relax. Next thing you know, you wake up from a nap to see that you missed dinner with your friend, and they have called you multiple times. They are upset and you feel horrible. “I can’t believe I did this. I’m so lazy! Why would anyone want to be my friend?” These self-critical thoughts are trying to motivate you to change. You are obviously upset that you missed dinner with your friend and made them upset. You don’t want to do that ever again. However, contrary to popular belief, self-criticism is not a good motivator. Instead of making a vow to change, you are now spending your night furious with yourself and beating yourself up. Let’s look at what science tells us about self-criticism. Self-criticism is defined as negative thoughts about the self, feelings of guilt, or fear of not meeting standards (Blatt, 2004; Blatt & Zuroff, 1992). Self-criticism is related to rumination (i.e., repetitively thinking about the same thought, event, or problem) and procrastination (Koestner & Zuroff). Also, self-criticism is inversely related to goal progress, meaning that the more self-critical someone is, the slower their progress toward their goals (Powers et al., 2007; Powers et al., 2009). Therefore, self-criticism may hinder us in achieving our goals! So, what’s the solution? What is going to help you achieve your goals? The answer may be self-compassion. Self-compassion involves being kind to yourself and not judging yourself based on your flaws or failures (Neff, 2003). In practice, self-compassion looks like treating yourself the same way you would treat a close friend. You might be thinking, “How is THAT going to help me achieve my goals? If I was nice to myself, I wouldn’t get anything done.” Well, research tells us that people who are self-compassionate are more likely to persist toward their goal, even after failing (Neff et al., 2005). Additionally, people who are more self-compassionate are less likely to be negatively impacted by failures (Hope et al., 2014). It seems that self-compassion prevents people from getting upset about their failures and giving up. Additionally, self-compassion is related to increased happiness and life satisfaction, as well as decreased rates of depression, anxiety, and stress (Neff & Germer, 2012). Going back to the dinner example, how would things be different if they had practiced self-compassion. Instead of saying “I’m so lazy! Why would anyone want to be my friend?” they say to themselves “Wow, I hate this. I had a long day, and now my friend is upset with me. I know I was tired, but I wish I hadn’t missed dinner. I really think I need to take a break right now. I’ll talk to my friend later, but right now I need to listen to some music and relax.” Instead of thinking about how horrible of a person they are, they can move on and maybe end their day on a more positive note. Now, what if you treated yourself with kindness? What if you practiced self-compassion? How do you think your life might change? I encourage you to try talking to yourself as you would a close friend. It could not only help you achieve your goals, but also improve your overall life. If you’re interested in self-compassion, please check out the following resources: By Sarah E. Ernst, Lab Manager While many individuals hope their summer is filled with once-in-a-lifetime adventures, summer is the perfect time to spend dedicated time gaining valuable experiences. Whether this is volunteering in a research lab, interning in a field related to your future career, or planning ahead and doing intensive seminars and preparatory courses, there are many ways for you to take advantage and get ahead. Personally, I did a combination of the three, and this has provided me with invaluable experiences that have shaped my future career interests and helped me to prepare for graduate school. As summer applications begin to open, I have a few pieces of advice, and suggestions for maximizing your summer-break opportunity:

In conclusion, summer is the perfect time to get ahead. By starting early, you can prevent the April stress of not having a plan and be better prepared to take on your future career. As Sophia Loren once said, “Getting ahead in a difficult profession requires avid faith in yourself. That is why some people with mediocre talent, but with great inner drive, go much further than people with vastly superior talent.” By: Irina Vanzhula, M.S.

Would you like to be happy? Of course! Why wouldn’t you? Most people believe that they must get rid of all negativity to create a better life. Abundant self-help books and websites teach us how to get rid of all negative thoughts and feelings and accumulate positive ones. With a brief internet search, you can find long lists of ideas on how to be happy. If they worked, we would all be very happy, all the time. However, 20% of adults in the US experience depression and 31% suffer from anxiety disorder in their lifetime (NAMI, 2018). Maybe long-term happiness is not possible and the struggle to obtain it contributes to our unhappiness. The most common definition of happiness is feeling good. This feeling is usually fleeting, and we put forth a lot of effort to try to hold on it. We chase things that we believe would make us happy, such as more money, a different job, a new relationship, having that “ideal” body, or not having to deal with some problem, such as a physical or mental illness. We spend a lot of time, energy, and money in the search for happiness, such as working more hours to get a new job and make more money, spending time on dating apps, dieting and spending hours at the gym, and looking for ways to control how we feel. We try to avoid unhappiness if at all possible. Unfortunately, all these strategies only work in the short-term (if they are effective at all) and we find ourselves searching for happiness yet again. This happiness chase is largely unsatisfying and can even lead to development or worsening of depression and anxiety. When we are unhappy, we often believe that something is wrong with our environment or even ourselves. Have you ever thought, “What’s wrong with me? Why can’t I be happy like everyone else?” or “Something is wrong with me because I am so unhappy”? We often believe that if we can’t achieve happiness, we have failed. Where did we get this idea that we should always be happy? The United States was built on the promise of the “pursuit of happiness” and it is one of the most important goals in Western culture. Our society assumes that happiness is a natural state and that mental suffering is abnormal. Suffering is often seen as a weakness or a character flaw. Instead, suffering is a normal part of life. Negative thoughts and feelings are not your enemy, and most things we value come with a full range of emotions. Having more money or a new job comes with exciting opportunities and new difficulties. A relationship brings love and joy, but also disappointment and frustration. Psychological pain and suffering are part of being human. Our brains developed to survive, which involves worrying about dangers, to evaluate our surroundings, and be dissatisfied with what we have. We would not have built fancy sky-scrapers if humans several hundred years ago were satisfied about their wooden hut. So many songs, paintings, and other works of art would have never been created if humans were always happy. Enduring difficult emotions is a valuable experience that makes us better individuals. Aristotle used the term catharsis to define emotional healing that comes through experience of one’s emotions. The goal here is not to say that you should feel sad all the time. However, instead of chasing feelings of happiness, I encourage you to pursue things that matter to you, with all the array of emotions that may come with them. Instead of a happy life, create a meaningful life worth living. If you think that you have to feel better and get rid of pain and suffering before you can do that, this is not true. You can be experiencing difficult emotions AND pursue your goals at the same time; it doesn’t have to be one or the other. Here is how to get started. 1. Accept that you cannot control your thoughts and emotions. Let’s do a brief exercise. Spend a few seconds trying not to think about a beach. Don’t think about the waves or how sand feels under your feet. Don’t think about how the breeze feels on your face. How did it go? Were you thinking about the beach the entire time? Now bring to mind your earliest childhood memory and get a picture in your head. Now try to erase the memory so it can never come back to you again. Were you successful? Can you still remember it? Finally, think of the last time you were sad and someone told you not to be. Did that work? Research actually tells us that trying to control negative thoughts and emotions contributes to more suffering (Wheaton et al., 2017; Beesedo-Baum et al., 2012). Instead, allow them to just be there and you will notice that they will soon pass. 2. Practice acceptance. Acceptance does not mean giving up or resigning to your fate. Rather, it means to see things the way they are instead of wishing they were different. If you are struggling with an illness, accept your reality as it is. You don’t have to like the situation or agree with it to accept it. Try writing about your situation, how it came to be and how it affects you. Don’t avoid discussing difficult thoughts and emotions. Instead of saying “I wish this didn’t happen to me and I wasn’t in so much pain” try “This happened to me and I am in pain now. I don’t like how I feel, and I can still move forward.” 3. Figure out what is actually important to you. A new job may not bring you satisfaction if work and career is not something you value. When thinking about your values, consider which ones are truly yours and which ones are placed on us by society. For example, it may be believed that women should value having family and children. Being skinny or fit is also highly promoted in our society. If you are pursuing one of these or other values, consider where they came from. Also, watch out for self-judgments in case you don’t value something that others expect you to. Be true to yourself. The following links can help you identify your true values. After you have done so, think of several small steps you can take towards those values. Here are some links with more information on how to practice accepting emotions: http://thegoodproject.org/toolkits-curricula/the-goodwork-toolkit/value-sort-activity/ https://thehappinesstrap.com/upimages/Long_Bull's_Eye_Worksheet.pdf References Harris, R. (2008). The Happiness Trap. Trumpeter Books: Boulder, CO. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/index.shtml Beesdo-Baum, K., Jenjahn, E., Höfler, M., Lueken, U., Becker, E. S., & Hoyer, J. (2012). Avoidance, safety behavior, and reassurance seeking in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 29(11), 948–957. What is it Like for Your Loved One in Eating Disorder Recovery? (And What Can You Do to Help?)7/9/2019 By: Caroline Christian, B.S.

As anyone who has recovered from an eating disorder knows too well, the road to recovery is never a smooth one. Seeing someone you care about going through this process can be frustrating and confusing. You want to do your best for them, but often it can be hard to even understand or sympathize with what they are going through. Eating disorder recovery is incredibly hard, and everyone going through this process has to work really hard as they endure a lot of really uncomfortable and scary things. If you are having a hard time understanding what eating disorder recovery is like for your loved one, here are just a few of the reasons why recovery can be so difficult. Giving up on your eating disorder can often feel like losing a friend, or losing a part of yourself. With other types of therapy it can be easier to want to get rid of the illness. For example, with therapy for depression, there is less motivation to want to keep the depression around, as depression doesn’t make you feel good. This makes it a little easier to stay motivated to kick it to the curb. However, eating disorders are not only an enemy, they can also be a friend (see Brenna’s blog post on When an Eating Disorder becomes a Friend). Even though part of your loved one knows that the eating disorder is holding them back, stopping them from enjoying time with family, ruining their relationships with friends, and keeping them in a cycle of disappointment from unrealistic standards, the eating disorder has also been there for them when nobody else was. The eating disorder gave them something to be proud of, it helped with their anxiety (even if just for a brief moment), and it helped them feel in control when everything else was going wrong. Especially if your loved one has been with their eating disorder for a long time, it can start to feel like a part of them. Disentangling this relationship in recovery can be hard, and it can feel like they are losing a friend, ending a relationship, or losing part of their self. This battle of friend vs. foe throughout recovery can drain motivation and make them feel conflicted and frustrated. Recovery means facing your biggest fears. Another difficult part of recovery is that most of the parts of an eating disorder are designed to make you feel safe and help you avoid (temporarily) scary things. For example, counting calories or avoiding certain foods help prevent the scary or uncomfortable expectation of feeling full, gaining weight, or being judged. But when someone recovers from an eating disorder, they have to face these fears head on. To know what this is like, I want you to imagine your worst fear. Let’s say it is spiders. Now imagine that you have to go into a room full of spiders (or whatever your biggest fear is) every day, and each day there are more spiders and bigger spiders. That’s what eating disorder recovery can feel like. To outsiders, eating certain foods and gaining weight may not seem like a big deal. But when your body is reacting to food and weight like it is a room of spiders, it can be really scary. Having to face your biggest fears isn’t easy for anybody. Your loved one recovering from eating disorders has to put a lot of energy into being courageous in the face of fear, which can be really draining. You have to put effort into recovery all day everyday. Unlike individuals recovering from substance use disorders, who abstain from using all together and can avoid situations where they may be tempted to some extent, individuals with eating disorders can’t abstain from food. We need food to live, our society is built around food, and messages about food are all around us. Because of this, everyday with an eating disorder means confronting food and other scary situations multiple times. Recovery requires putting thought, effort, and strength into recovery everyday, whether it be the thought that goes into following a meal plan, the effort it takes to challenge negative body talk, or the strength to confront, instead of avoid, difficult emotions. The nonstop effort your loved one has to put in to recovery is a huge part of what makes the process so exhausting and difficult. If you have a loved one who is struggling in eating disorder recovery, here are a few words of advice from an eating disorder therapist that may help you be there for them as they push through the inevitable hard times. 1. Be patient with the process. Eating disorder recovery can be a slow and difficult. A few months down the road, you may wonder why your loved one is still not eating as much as you’d like, or not hitting goals you have for them. The process of recovery takes a different amount of time for everyone, and pressure from family and friends to get better faster will not speed it up. Try to be patient with your loved one and their own personal journey, and know that just because it has been a long journey, doesn’t mean it is endless. 2. Don’t take things personally. You may notice that your loved one is more irritable, tired, or withdrawn throughout their eating disorder recovery. It can be easy to get frustrated with them. Instead of being offended if your loved one doesn’t come to your events or support you like they used to, know that they are going through a lot, and they may not have a lot left to give. Try to do things to give them support and energy, instead of asking more of them. 3. Try to open lines of communication. Everybody in eating disorder recovery utilizes their support system in a different way. Some people benefit from talking about it, while some would rather process things on their own first. The best thing you can do is let your loved one know that you are there for them and would love to talk with them if and when they want to. You have to find your own balance in which you are not forcing your loved one to talk about their struggles with recovery, as this can add more pressure and frustration for them, but also not avoiding the topic, because that can feel very isolating. 4. Educate yourself. Continue to try to read, talk, and learn about eating disorders. They are much more complicated than just not eating enough, or eating too much. They are complex psychological disorders that researchers are still trying to fully understand and treat. Learning about the disorder and how you can fit in to the picture, will help you be more aware about what your loved one is going through and how to not add stress. For example, not promoting dieting or weight loss around them, as diet culture can make ED recovery more difficult. 5. Be encouraging. Most individuals in eating disorder recovery struggle with slip-ups throughout recovery, which can feel really discouraging. Your loved one in recovery is going to be hard on themselves, and they may even feel like a “failure” when this happens, so what they need from you is encouragement. Try to remind them of all the little victories they have throughout recovery. Remind them that you are proud of them and their growth so far, and tell them about all the awesome changes you have already noticed. This can help them feel supported and energized to keep going when it is hard. Understanding why eating disorder recovery can be so difficult is an important step to help you better support your loved one through this difficult journey. For more tips on how to support your loved one in various stages of recovery check out NEDA’s advice for caregivers. This post was written by Shruti Shankar Ram, who is the EAT lab’s outgoing lab manager and will be starting her PhD program in Fall 2019 under the mentorship of Dr. April Smith at Miami University. Shruti also applied during the 2016-2017 cycle and then again during this past cycle (2018-2019). Miami University was her top choice program. Persistence pays off!

While my time at the EAT lab may soon be coming to an end, it marks the beginning of my graduate school career, and the culmination of a successful round of clinical psychology doctoral applications and interviews. Potential applicants for psychology graduate school programs often need to seek out a lot of information on the application process on their own. Luckily, I had the support and advice from graduate student mentors and professors who helped me on my journey, and I have been able to reflect on some of the things other potential graduate school applicants should know before undertaking the process of applying. Please keep in mind that it is important to consider several factors when deciding which programs to apply for, whether it be doctoral or master’s level programs, but the advice given here will primarily pertain to clinical psychology PhD programs: 1. Research your potential mentor(s) thoroughly, and have as solid of an understanding of your research interest as possible. Especially for PhD programs, it is important to consider your potential mentor more so than the program or university itself, as the work you do in their lab will define your career and PhD training. Spend time thinking about your specific research interests and which mentors will align best. This will also make writing your statement of purpose much easier, and faculty are pretty good at telling when you have a genuine interest in the work and a good fit with their lab. The places I interviewed were the places where my research interests fit best with the research interests of the mentor, regardless of my current skillset or what I'd need to learn after arriving at the program. I think partly this is just because it makes it a lot easier to talk with the mentors about follow-up studies and you're more interested in papers they've probably read as well, so it's just easier to interview. Also be up front with POIs about your research interests, and don't try to change your interests to fit with the lab in the hopes it gets you an acceptance. You're going to be spending several years in this program, so you want to make sure you're doing work you enjoy. Also, they can tell a student who is truly passionate about what they do from one who isn't. 2. Make sure you REALLY want it before you apply. The application process for PhD programs is way too stressful to just do it without extensive thought and planning. Despite the common misconception, you do not necessarily need a PhD to treat patients and be a therapist. As I want to pursue a career in research and academia, I only applied to PhD programs in Clinical Psychology. However, if I wanted to primarily be a practitioner, I would have considered a master’s degree such as a Master of Social Work (M.S.W.) or Master’s in Counseling Psychology (M.S. or M.Ed.). A PsyD (Doctor of Psychology) is another alternative to a PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) for those oriented more towards therapy, and offers more opportunities for higher level practice administration and supervision, but does typically involve more debt. Another important consideration is that PhD programs are typically fully funded, but PsyD and Master’s programs are not, but they also accept far fewer applicants because of this. Think carefully about what your long-term goals are and what degree might make more sense for you, your interests, and finances. If being a clinician is your primary interest, opt for a psychotherapy program that's literally half the amount of time and effort. So while you may have more financial debt, you will have less of a time debt. 3. Talk with anyone in your current department who will advise you. Talk to graduate students, faculty you've worked with, faculty you haven't worked with, etc. Be respectful of their time because everyone is busy, but I asked for as many opinions as I could get. Current graduate students can help you identify potential mentors, assist with personal statements, mock interview you, and potentially even go over offer letters with you. It can be really helpful and insightful to get the assistance of someone who has been through the same process. 4. START EARLY. Everyone that applies to graduate school will tell you to start early, but seriously, start early! Writing statements of purpose and studying for and taking the GRE can be time consuming, so work ahead so that you have everything ready far in advance of your deadline. 5. DO sweat the small stuff. Psychology PhD programs have an acceptance rate of around 7%. Before I applied, I had no idea it was more difficult to be accepted into a PhD program than it was to be accepted into medical school. Because most PhD programs only accept about 5-8 students per year, and each lab typically accepts one student, even little things can make a big difference in your application. Think realistically to make sure your GPA, GRE scores, strong letters of recommendation, research experience in your CV, and number of posters/publications are up to the standard of the graduate schools you are applying to before you apply. PhD programs are getting more and more competitive, so it is becoming more common for people to take years off to work and get research experiences before applying and entering PhD programs. 6. Apply to as many schools and POIs as you can without sacrificing too much of your research interests. As PhD programs are so competitive, it is a good idea to maximize your chances by applying to as many programs as possible. I was advised to apply to at least around 11-15, and I ultimately applied to 13. That may seem like a lot, but with the amount of luck that goes into this process, you need to maximize your chances. It's pretty common to apply to many and then only get 3-5 interviews. There are many individuals with strong applications, but who only apply to 2-3 programs, which considerably lowers their chances. If you have a niche interest, it is a good idea to apply to programs of both your primary and secondary research interest, as long as the labs will allow you to study both. 7. There's a lot of luck and connections that go into this process. Because PhD programs are so competitive, small things like connections can make a big difference. Potential mentors talk to several students, and sometimes they might want to take all of them but just can't. Network as much as possible by attending conferences and making a note of all talks and poster presentations given by the labs you are applying to – attend them and introduce yourself and your intention to apply to both the P.I. AND their graduate students. Everyone in the lab typically has some say in the application and interview process, so make a good impression and network with all lab members you see from those labs! 8. BE RESILIENT. When I interviewed at doctoral programs, a common answer I received when asking potential mentors about what they were looking for in applicants is resilience. The whole process of applying to psychology doctoral programs can be disheartening, and rejection is inevitable – it may take several rounds to be accepted to a program. Not everyone is ready at the same time to start graduate school, so do not be afraid to take time off to get more research experience if needed. I first applied to doctoral programs my senior year in college, and did not get accepted until I applied again two years after graduating and working at the EAT lab during that time. Working at the EAT lab allowed me to develop and refine my research interests and has set me up for success in graduate school, and I have no regrets, no matter how much the initial rejection stung. Initial rejections will pay off in the long-run, as long as you keep working and trusting in the process. If you are planning to undertake the process of applying to psychology doctoral programs – good luck! Remember to not only work hard, but show yourself self-compassion during this process. It is impressive to even apply for these programs! No matter how difficult it may seem to get into a doctoral program, if clinical psychology and research are truly your career goals, keep working towards those goals and you will get there. Hard work and persistence pay off! |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

- About

- People

- Our Research & Publications

-

Participate in Research

- Personalized Interventions and Outcomes: Navigating Eating Disorder Experiences and Recovery (PIONEER) Study (Online)

- Youth Eating Study (YES!)

- Tracking Restriction, Affect and Cognitions (TRAC) Study (Online)

- Virtual Reality Study

- Facing Eating Disorder Fears Study (Online)

- Personalized Treatment and CBT-E Study (Online)

- Body Project Summer Camp

- The Body Project

- Clinical Screener Study (Online)

- Clinic, Supervision, and Consultation

- Blog & In the Press

-

Archived Studies

- Predicting Recovery Study (Online)

- Online Single Session Resources

- Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences (RISE) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness Study

- Personalized Treatment Study

- Online Imaginal Exposure Study

- In-Vivo Imaginal Exposure Study

- Daily Habits 3 Study

- Daily Mood Study

- COVID-19 Daily Impact Study

- Conquering fear foods study

- Louisville Pregnancy Study

- Approach and Avoidance in AN (AAA) Study

- Web-Based Mindfulness for AN & BN Study

- Barriers to Treatment Access (BTA) Study!

- Mindful Self-Compassion Study

- Network EMA Study

- Legacy of Hope Summit Report

- DONATE-CURE EATING DISORDERS!

- Directions

- Statistical Consultation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed